Las Christmas (5 page)

I loved these hybrid celebrations, half day and half night, for they seemed to combine the best of both worlds. But, sadly, biculturalism is a balancing act that topples with the generations, and by the end of our third decade in exile our Nochebuenas had changed again. Many of the older members of the family passed away in the 1970s and 1980s; other aunts and uncles were either too old to travel to Miami every December, or too infirm to leave their houses. When his wife died, my uncle Pedro stopped celebrating holidays altogether. (Now he gets on a plane on the morning of December 24 and spends Christmas Eve at the blackjack tables in the Bahamas; a

noche buena

is when he doesn't lose too much money.) Then also, those in my generation have their own lives and can't always make it down to Miami for Christmas. Once every few years, some of us still coincide in Miami for Nochebuena, but it seems to happen less and less often. With the death of the old-timers, Cuba is dying too.

Every Nochebuena for the last several years my mother grumbles that this will be her lastâthat she's getting too old for all of the preparationsâbut come the following year she roasts another leg of pork, cooks another pot of

congrÃ,

and tries to get the family together. However Americanized she may say she is, she doesn't seem willing to give up this Cuban custom. Old Havanas are hard to break, but for Nena and Gustavo, Nochebuena has become a mournful holiday, a reminder of how much things have changed in their lives. Years ago Nochebuena used to be a time to remember and celebrate things Cuban. The ritual toast, “Next year in Cuba,” set the mood for the evening, a mood both nostalgic and hopeful, for the Nochebuenas of yesteryear were a warrant on the Nochebuenas of tomorrow. During those very good nights, everything harked back to Cubaâthe celebrants, the food, the music, the customs. At no other time of the year did Cuba seem so close, did

regreso

seem so imminent. Every year we heard my father's favorite chanteuse, Olga Guillot, singing “White Christmas” with Spanish lyrics. Every year we danced to “La Mora,” an old Cuban song whose questioning refrain was uncannily relevant, “

¿Cuándo

volverá, La Nochebuena, cuándo volverá?

” “When will it return, Nochebuena, when will it return?” Soon, we all thought, very soon. It turned out not to be so.

In all the years I have resided away from Miami, I've missed only one Nochebuena, and that because one year we decided to spend Christmas at our own home in North Carolina, an experiment that didn't turn out well and won't be repeated. As long as my parents are alive and willing, I'll go to their house for Nochebuena. Although the celebration and the celebrants have changed a great deal through the years, more than I and they would have liked, Nochebuena remains for me the holiestâif no longer the happiestâ night of the year.

But I have no illusions. Our Miami Nochebuenas have come to resemble those skeletal Christmas trees from Cuba. I could make a joke and say that you can't make roast pig from a sow's ear, but this is no joke. After my parents have passed away, I hope not until many years from now, I will celebrate Nochebuena in Chapel Hill with my American wife and my almost-American children. Instead of going to Miami, I'll be staying put. I'll be a squatter, not a roamer. But I will be squatting far from home. I know that in Chapel Hill my Nochebuena traditions will suffer a further attenuation, and when this happens I'll find myself in the position that my father occupies nowâI will be the only Cuban rooster in the house. The good night, which became less than good in Miami, may well become not good enough in Chapel Hill. My reluctant but hopeful wager is that the not-so

-buena

Nochebuena will be followed by an excellent Christmas.

Cuban

CongrÃ

RICE AND BEANS

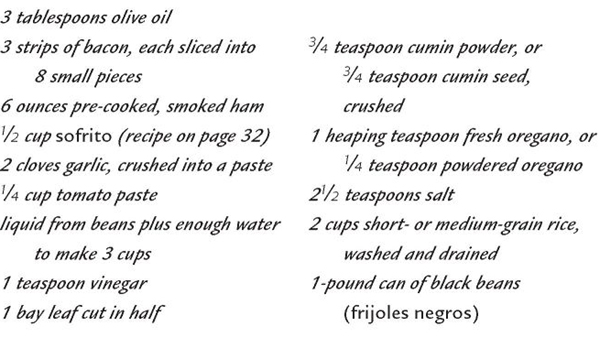

Heat the olive oil in a large heavy pot. Fry the bacon over medium-high heat until golden. Remove bacon and drain on paper towels. Set aside.

In the olive oil/bacon grease, fry the ham until well heated and crispy. Remove the ham and set aside.

Lower heat to moderate. Add

sofrito,

garlic paste, and tomato paste. Cook for 3 minutes, stirring frequently.

Raise flame to high and add the liquid from beans, the vinegar, bay leaf, cumin, oregano, and salt. When boiling, add rice and beans. Stir to mix well.

When it boils again, lower flame to moderate and cook uncovered until somewhat dry.

Reduce flame to low, add half the reserved ham cubes, and stir into rice. Cover and cook for 15 minutes.

Stir rice again, cover, and cook another 15 minutes, or until rice is tender.

Serve hot, decorated with the rest of the ham pieces and the fried bacon. For more flavor, stir in 2 tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil before serving.

Makes

6

servings

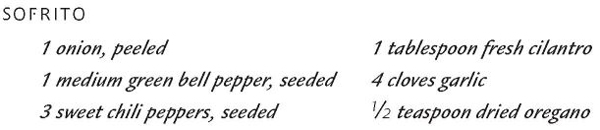

SOFRITO

Whir all ingredients for the

sofrito

in a blender until chopped. Store in the refrigerator in a tight-lidded container.

Denise Chávez

Denise Chávez is a native of Las Cruces, New Mexico. Her novel,

Face of an Angel

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux), was awarded the

1994

Premio Aztlán and the

1995

American Book Award.

She is also the author of

The Last of the Menu Girls,

a collection of interrelated short stories. Her forthcoming novel,

Loving Pedro Infante,

will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. A performance

artist as well as a writer, Chávez tours in her one-woman

show,

Women in the State of Grace,

throughout the United States. She has been the Artistic Director

of the Border Book Festival, based in Las Cruces, since its inception in

1994

.

BIG CALZONES

In memory of my parents,

Delfina Rede Chávez and E. E. “Chano” Chávez

IT WAS A TRADITION in our family that each year one of us was presented with an unusual gift: an enormous pair of the biggest, whitest, stretchiest polyester panties you have ever seen, size queen-ultra-mega-4X, clownish, enormous drawers. Just to look at them made you laugh out loud. Mother bought them at Aaronson Brothers Clothing store on Main Street, in our little hometown of Las Cruces, New Mexico. Each year, she wrapped this huge pair of

calzones

in the loveliest paper, tied with an elaborate bow, and gave them to some unsuspecting but delighted soul in our immediate family. The package was opened to squeals of laughter. You never knew when it would be your turn to receive the panties.

Mother's sense of humor was legendaryâand sometimes diabolical. Despite her propriety as a teacher and single mother, she had a great sense of the ridiculous and liked to take photographs of people in disarray. She often ambushed my sister or me in the bathroomâa towel draped loosely around a naked body seated on the toilet, hair in curlers, reading the

National Enquirer.

She kept an album of crazy photographs that I still treasure today.

The first year, I was the one who received the big

calzones.

As I opened the beautifully wrapped gift, I had no idea why there was a special twinkle in my mother's eye. We all had a huge laugh as we passed the giant panties around and tried them on. Mother was a large woman, but she, too, modeled the panties. I snuck out of the room to get her camera and catch her in the act.

After Christmas, the

calzones

went into Mother's gift box, a large cardboard bin stored in the living-room closet behind the winter coats and umbrellas. If a birthday came around without warning, if there was an unexpected wedding or a forgotten anniversary, she would send us to the box to find an appropriate last-minute gift. The box held the leftovers given to my mother by her third-grade students, expendable gifts like cheap leather wallets, lifesaver books, inexpensive vases, an assortment of gloves, scarvesâand one special item, a red plastic wallet with a window on the front displaying a postcard-size portrait of a handsome and lean Jesus Christ.

We called it the “Jesus wallet,” and like the big

calzones,

it was given to one or another family member every Christmas. But unlike the giant panties, the Jesus wallet was a serious giftâtoo serious for teenage girls. We never used the wallet, but each year, secretly, put it back in the gift box for someone else. By the time another Christmas came around, Mother often forgot which of us had been given the Jesus wallet the year before.

These perennial Christmas gifts were but two of the many presents we received each year from our mother. She never gave us each one or two, or even six or eight gifts. The numbers ranged into the twenties and sometimes thirties. Christmas with my mother never meant lack but overabundance. She gave and gave and then gave more. She was the most generous person I have ever known. If she gave you two or three pairs of socks, they were never wrapped together. Each pair had its own distinctive paper, bow, and gift tag. If she gave you a pair of shoes, each one was wrapped separately.

You could count on a huge individual pile of gifts. One by one, each daughter opened her gifts, and then ceremoniously tried on her clothing, hats and shoes, displayed and commented on any number of offbeat and original items. The process took a long time, but time was all we had then. To our mother's delight, after we'd tried on every single outfit, we'd leave them on display in the living room for several days, draped over the couch. Later, when I became the caretaker of my elderly father, I found myself doing the same thing. I laid out all his gifts on the couch for him to see, his new outfits, his new towels and blankets, his flannel pajamas, his Velcro tennis shoes.

Mother was so proud to see us wearing the things she'd given us. She was an impeccable seamstress and made many of our dresses and suits, purses, pillows, blankets and quilts. Anything you wanted or needed, she could copy. We complained as we stood on wooden chairs in the TV room while she pinned up our skirts or marked a chalk line on the spot where a hem should go. I often whined while she ordered me to “Turn, turn, no, too far, go back.” But I loved the clothes she made us. And we loved her, although she sometimes scared us.

Mother could be more imposing than Sister Alma Sophie, the principal at Holy Cross Elementary School, known for her strictness and the lingering smell of her false teeth. Mother could be tougher than Father Ryan, known for his intractable one-sided stance, his Hollywood good looks, wasted on a priest. My mother was the original bogeywoman, a disciplinarian who stopped us with her upraised hand and a razor sharp “

Ya,

that's enough.” A “

Ya

” from her could stop a speeding train.

My parents split up when I was ten. The divorce dealt a great blow to my mother's spirit, but it didn't prevent her from inviting my father to spend Christmas and many other holidays with us, nor did it prevent him from accepting her many invitations. Whenever he drove down to Las Cruces from his home in Santa Fe, he always remembered to bring along his dirty laundry, thrown carelessly into the trunk and onto the back seat of his old pea-green Pontiac. A banged-up mess of a car, Mother nicknamed it “Jaws” for its gaping trunk held down by several twisted coat hangers. Daddy never stayed too long or brought too many clean clothes. Each year, religiously, he would make the long trek from his northern home to southern New Mexico to be with his family for Christmas. He always arrived late, sometimes slightly tipsy, other times fully drunk. And he always left much too soon. At first, he shared my mother's bedroom. After a few years, he began to sleep in the TV room, although I can't say with certainty that he didn't cross her threshold once or twice. They loved each other passionately but had little in common. My mother was a devout Catholic who went to church at six o'clock every morning. My father was an alcoholic who loved people, especially women. He liked to stay out late, and to him, freedom meant everything.

Mother was probably even more generous with my father than she was with us, and his pile of gifts was always high. Daddy was never much of a shopper. He bought his clothing at Kmart and his presents at Bonanza City. Daddy bought everything at the last minute. There were years he didn't buy anything at allânot even a gift for his aged mother, who doted on him and was always waiting for his visits. He might give Mother a toaster, a set of steak knives, or a telephone notepad, his wonderful rolling handwriting on the back: “To Mother with Love, Daddy.”

One year he bought my sister and me flouncy, frilly dresses that were much too babyish for the grown-up young ladies we had become. I was deeply embarrassed by this thoughtlessness, mortified to be given such a silly thing. The dress fit me and I wore it on Christmas Day, but I hated being seen in such a “little girl's” outfit. To my father, we were still his babies. He knew so little about us. His stories and memories were stale and outdated.

Once he gave us money to buy our mother a gift, and took us to a discount store where we bought all sorts of useless and inexpensive things. I felt badly that we had to buy her such junk and even worse that my father was so cheap. Mother just blinked at her ugly gifts.

A few years before she died, when I had a little money, I gave her a mother-of-pearl ring. It was the only really good gift I ever gave my mother. The ring came in a little box and she gasped with joy when she opened it. I remembered the adage “Big gifts come in small boxes.”

It never mattered to my mother what gifts she received, or so she said. What mattered was the gifts she gave to us.

WHEN I THINK of my life, it's times like Christmas I miss the most. Before midnight mass, friends and relatives might drop by our house for my mother's famous tacos, her high, light

sopaipillas,

her

frijoles,

chile and

arroz

or her

pan,

which she made with tortilla dough. Not much of a cook year-round, Mother came to life at Christmas. My sister and I roamed through the house, replenishing food and picking up dirty plates. I yelled from the dining room, to everyone's delight,

“¡Delfina, más tacos!”

I savor my memories of those Christmas Eve masses in that long ago when St. Genevieve's Church was still standing proud. I tried so hard to stay awake during the interminable rotations of kneeling, standing, and sitting, the Communion walk a needed respite from inertia. My father stood in the back with all the other men, while we women took any available seat we could find. (My mother swore she could tell my father's cough from anyone else's in the crowd.) As we lumbered out of the church around one-thirty Christmas morning, my father would join us. The cold, brisk December air hit us, but not too harshly, for our winters were always mild and it rarely snowed.

We rode home through an immense darkness, eagerly anticipating the opening of gifts. We usually went to bed at two or three a.m., that delicious time when sleep comes gently and so easily. We'd sleep late the next morning, knowing we'd already fulfilled our religious obligations by going to mass the night before. Those early morning hours were so sweet, so magical. They were a time of no time, a time that fulfilled and satisfied and brought peace and love. We lay in bed full of tacos and

capirotada,

my mother's wonderful bread pudding, her

empanadas de calabacita,

and the family mincemeat dish we called “pasta,” made exclusively by the Chávez women. It was handed down from Grandma Lupe and kept alive by my aunt Elsie, whose recipe stated that the pasta needed to be cooked “until it looks like caca.”

On Christmas Day we'd go to my uncle Sammie's house on the next block, for his famous

menudo,

then drop in on my aunt Elsie Chilton, who lived at the end of our short street. My father's younger sister, Aunt Elsie, was the unofficial Chávez family matriarch and the caregiver for over thirty years of my father's mother, Grandma Lupe. A wizened lady of advanced age with a powdered pale face, she looked a lot like George Washington. Grandma Lupe lived to the left side of Aunt Elsie's laundry room, and it was her duty to fold the clothing for my aunt's eight children. A set of wooden shelves held all of my grandmother's worldly possessions: statues of Our Lady of Guadalupe and St. Jude, myriad rosaries, boxes of greeting cards, soft handkerchiefs (each of them folded and refolded countless times), old Christmas wrap, and faded photographs of her children both living and dead.

My aunt's Christmas trees were always long, thin afterthoughts, never much to look at. My grandmother sat in her wheelchair in her usual spot in the center of the room, peering out like a bird and then calling out with joy as she saw her favorite son, “Chano!”

Aunt Elsie's family was large and boisterous. The children and parents chose names each year and bought a gift only for the person whose name they had selected. My mother always brought gifts for my grandmother, my aunt and uncle, and for her goddaughter, Charlotte, whom my grandmother, in her soft

Mejicano

accent, sounding out the long “ch,” called “Charlie.”