Read Layayoga: The Definitive Guide to the Chakras and Kundalini Online

Authors: Shyam Sundar Goswami

Layayoga: The Definitive Guide to the Chakras and Kundalini (6 page)

‘Hathayoga solves this problem by controlling the sensory projections and senso-mental radiations by making the body-apparatus sensorially inoperative by kumbhaka. But this is a very difficult method. In rajayoga this problem does not arise. The rajayoga process of concentration starts when a student is already established in concentration. Rajayoga aims at purifying consciousness to the highest degree and transforming it in the state of samprajñata samadhi (super-conscious concentration) which will be effortless and the normal mode of the mind. The final goal of rajayoga is to get this super-purified and super-illuminated consciousness absorbed completely into Supreme Consciousness in asamprajñata samadhi (non-mens concentration). Layayoga achieves this goal by arousing Kundalini (the spiritual aspect of the Supreme Power) and gets all the cosmic principles absorbed into it. But the awakening of Kundalini requires deep concentration. So a modified method, termed bhutashuddhi, has been introduced to develop concentration.

‘Mantrayoga presents a unique method which is extremely helpful for making concentration deep, real and normal. This method has also been adopted in layayoga. The method consists of the following factors:

‘First, the consciousness is moulded into the mantra-form through the mental transformation of the waikhari (gross, sensory) sounds of the mantra. By the mantra-practice, the mantra-form will gradually be changed to living mantra when consciousness is in a state of concentratedness. Then, ultimately from the living mantra, living God, in an appropriate form, emerges, and concentration now becomes deep, real and automatic. The living God in form is called Ishtadewata, that is God who appears in a form from the mantra-sound by his will.

‘In order to make the mantra-work successful, it may be necessary to apply certain specific processes which are as follows: (1) Achamana; (2) Kaminitattwa; (3) Mantrashikha; (4) Mantrachaitanya; (5) Mantrarthabhawana; (6) Nidrabhaṅga; (7) Kulluka; (8) Mahasetu; (9) Setu; (10) Mukhashodhana; (11) Karashodhana; (12) Yonimudra; (13) Pranatattwa; (14) Pranayoga; (15) Dipani; (16) Ashouchabhaṅga; (17) Utkilana; (18) Drishtisetu; (19) Special dhyana; and (20) Kamakaladhyana.

‘These processes are highly technical and are executed with appropriate mantras and with concentration. They should be learned from a guru.

‘It is not an easy thing to make Ishtadewata appear from the mantra. It is also not an easy thing to make the mantra living. So long as it is not possible to achieve this, an easier means has been adopted in mantrayoga for the development of concentration. It is this: a replica of Ishtadewata as an object of concentration is made. For this purpose, a gross image from some suitable material is made. This image is not an imaginary representation of Ishtadewata, but a close copy of the real form. It is a tangible form easy for the sense-consciousness to hold. It is not idolatry. This is a wrong term, only used by those who are ignorant of the subject.

‘By seeing the gross image of Ishtadewata again and again, a clear picture is formed in the sense-consciousness. The gross image is made life-like by mantra, and in certain cases quite living, and then it begins to be steady in the consciousness, and gradually fills the whole consciousness, and no other objects penetrate consciousness. Now concentration becomes very deep. This state can only be reached when the body and mind are purified by mantra, and the life-impartation to the image is done by mantra. In this manner, concentration becomes real and deep.

Ishtadewata is God in form. The form arises from the living mantra and is created by God himself. So it is not imaginary. God appears in form, otherwise the mind will not be able to receive it. It is absolutely necessary to have a form which can be held in consciousness in concentration.

‘There is also mental worship which helps to establish concentration. In the muladhara chakra, Ishtadewata is worshipped with the smell principle; in the swadhishthana centre, with the taste principle; in the manipura centre, with the sight principle; in the anahata centre, with the touch principle; in the wishuddha centre, with the sound principle; in the hrit chakra, with all the five principles; and in soma chakra, with spiritual qualities. Then a student is able to hold in his consciousness the pure luminous form of Ishtadewata in concentration.

‘Thereafter, concentration develops into samadhi in which the most subtle form of Ishtadewata is held naturally in superconsciousness. This is the last stage of form. Then comes the realm of formlessness. Here, Ishtadewata is without form; he is now the Supreme God This is the stage of asamprajñata samadhi.’

Now I had a better opportunity, because of our intimate relation, to observe the mode of life the Master was leading, his actions in everyday life. I learned from his teachings as well as from his life. I found that yama and niyama were fully established in him. Truthfulness was the cornerstone of his life. He did not touch any thing which was acquired in an immoral way. He was content, and, usually, he remained absorbed in himself and silent, even when there were people around him. He had superpowers, but he rarely used them.

The Master observed brahmacharya (sexual control) up to the age of twenty-eight years. During this period, he led a continent life for eight years while with his wife. Thereafter, he had children. Then he devoted himself to perfect the process of Adamantine Control.

I have learnt from his teachings and life that premature continence does not help in controlling the sex urge. Sexual excesses are also enervating. To be away from the sex objects also does not help. Senseless sexual gratification decreases power. Sexual efficiency demands control while alone as well as in contact.

Sexual efficiency is closely related to physical vigour, mental creativity and concentration. It should be developed by appropriate means. Its component parts are: (1) sexual passivity while alone and also together; (2) sexual creativity at will; (3) sexual purity; (4) adamantine control.

On one occasion, the Master talked about the four great systems of yoga. He said: ‘There are four great systems of yoga: mantrayoga, layayoga, hathayoga and rajayoga. Each has its own characteristic feature, each has its specific practices. Each aims at the attainment of samprajñata yoga, and through it asamprajñata yoga. This is the final form.

‘Mantrayoga is that form of yoga, in which word-thought forms, associated with the multiform consciousness, are transformed into supraword form, that is mantra. Mantra effects the concentrated form of consciousness which leads to samadhi.

‘Mantra is the suprasound power in word form. When the mantra is rightly worked upon, it becomes a living power from which arises the living Ishtadewata—God in form. Now concentration becomes very deep.

‘Layayoga is that form of yoga in which concentration is developed through the absorption of all cosmic principles, leading ultimately to samadhi.

‘Hathayoga is that form of yoga in which dynamic livingness, with which is associated the oscillatory form of consciousness, is transformed by the pranayamic process into a passive form of existence which effects concentratedness of the consciousness, leading to samadhi.

‘By the pranayamic breath-control, a non-respiratory state is gradually developed in which a natural cessation of respiration occurs. This is called kewala kumbhaka. In kewala kumbhaka concentration becomes the normal mode of consciousness.

‘The control of the inspiratory and expiratory acts is done by sahita pranayama. An internal purification is necessary for making the pranayama work. For this purpose, internal cleansing, purificatory diet and control exercise are instructed in hathayoga. By the pranayamic process, the body begins to be refined normally, all the vital activities are normalized and brought to a new level and normal health is established. This super-purification is called nadishuddhi.

‘At this state, health, vitality, absence of unpleasant body odours, wholesome breath, appearance of a pleasing, slightly fragrant smell, cheerfulness and calmness and concentratedness of the mind—all these arise.

‘Rajayoga is that form of yoga in which concentration is developed to non-mens concentration—asamprajñata samadhi which is rajayoga—the highest form of yoga.’

I have seen the Master in a state of samadhi. He usually assumed the corpse posture (shawasana) in which he lay on a bed with his face upward, and arms by his sides. The body remained completely motionless, without breathing, without pulse, and, apparently, without signs of sense activities. In this death-like condition he would stay for long periods.

He also used to go into very deep concentration in a sitting posture. It was his common practice to sit outside in the sun with a newspaper, supporting his elbows on a small stool, placed in front of him, as if he were reading. He might perhaps read the paper for a short time, but very soon he became still and his eyes closed. He remained in this position for hours. Shouting often could not make any impression on him. Many times it was necessary to awaken him for his lunch by shaking him vigorously. After being aroused, when he first opened his eyes, his look appeared meaningless, as if he was not of this world. After some time, he came back to his worldly self.

One day I asked the Master: ‘Is the mind unconscious and dark while the body remains death-like in samadhi?’

The Master replied: ‘No. The mind is super-conscious and super-illumined.’

S. G.

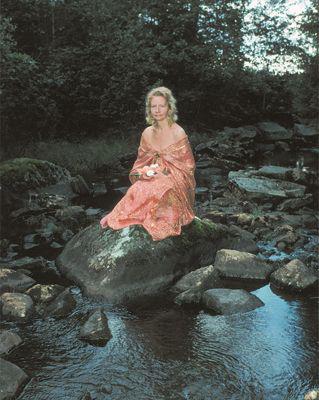

I The Author (at the age of 87)

II Wani

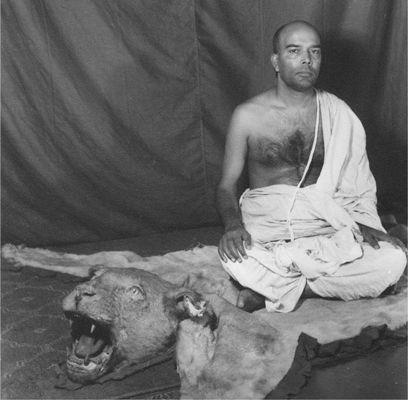

III Acharyya Karunamoya Saraswati

IV Master: Sreemat Dwijapada Raya

V An Ancient Picture of the Chakra System (belonging to the Author’s library)