Leaving Cold Sassy (9780547527291) (19 page)

Read Leaving Cold Sassy (9780547527291) Online

Authors: Olive Ann Burns

Â

Â

Â

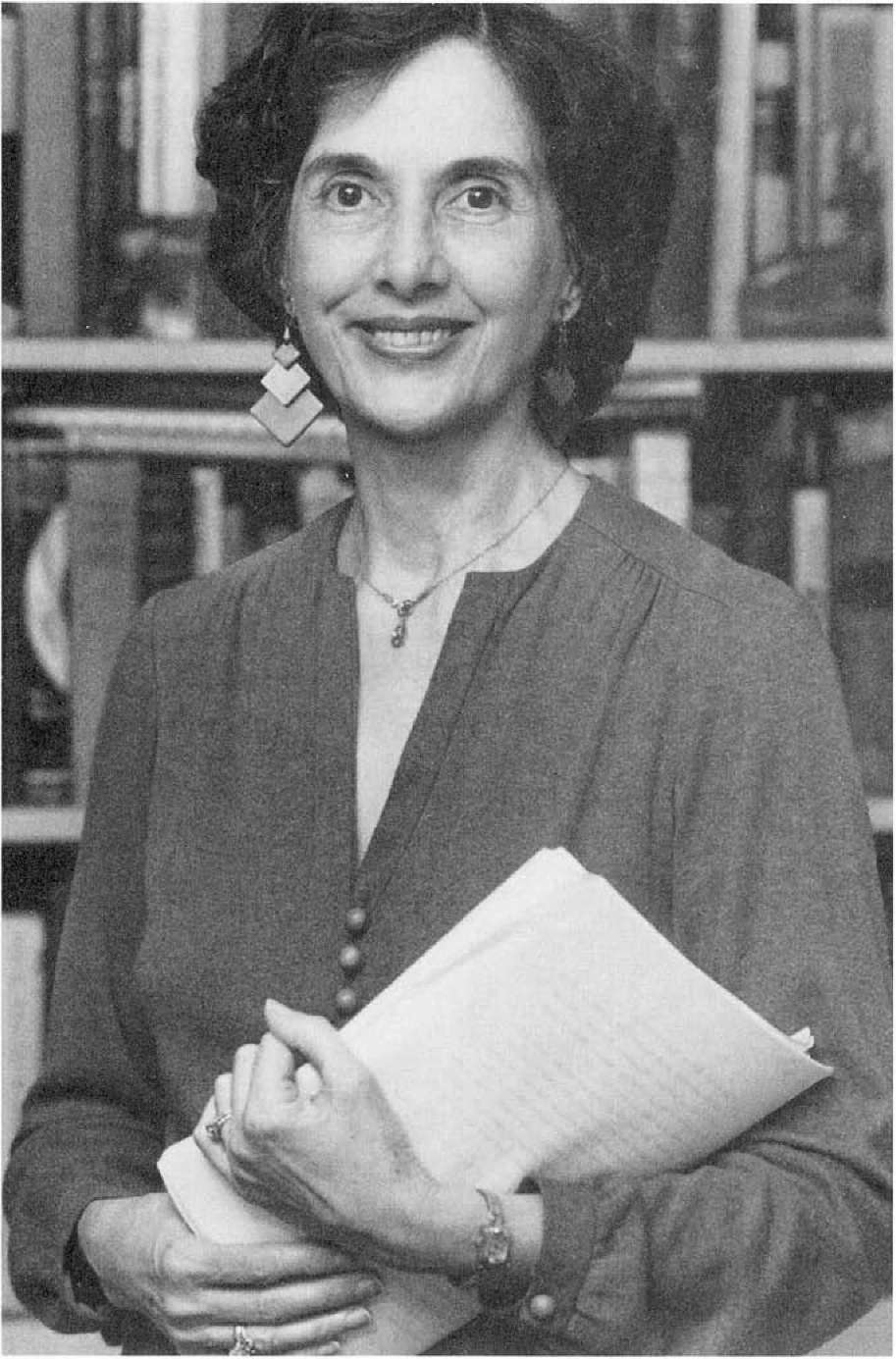

Carter (Conway-Atlanta Photography

)

Â

Cold Sassy Tree,

ready to address a crowd, “I am a ham,” Olive Ann admitted.

Â

Â

Time, Dirt, and Money,

1989

A Reminiscence

O

LIVE

A

NN

B

URNS

lived sixty-five years and completed only one book. Since its publication in 1984,

Cold Sassy Tree

has become an American classic, selling over a million copies worldwide and still going strong. It has inspired accolades and fan letters from readers young and old, from all walks of life. Schoolchildren and cancer patients, Broadway producers and country farmers have written to say that their lives were touched, even changed, by this remarkable novel. Barbara Bush named

Cold Sassy Tree

one of her favorite books; Oprah Winfrey, Craig Claiborne, and B. F. Skinner wrote grateful letters to its author.

Now, nearly ten years after its publication,

Cold Sassy

Tree

is widely regarded as one of the best-loved novels of our time. It is required reading in English classes across the country; it still appears on best-seller lists, from Washington state to the East Coast, and fan letters continue to arrive, from people who have fallen in love with fourteen-year-old Will Tweedy and the story he tells of life in a small Georgia town at the turn of the century. Over the years, there have been literally hundreds of such letters, and rare is the one that doesn't ask for a sequel to

Cold Sassy Tree.

People who read Olive Ann's book can't help feeling they know herâthat she must be just like them, except that she happened to write this wonderful novel. That is how Olive Ann herself felt. “If I can write a book,” she often said, “anybody can.”

I met Olive Ann Burns for the first time in Atlanta, on the day

Cold Sassy Tree

was published. But by the time we finally met in person we were already fast friends. During the preceding year we had talked on the phone every few days, and we had embarked on a correspondence that was to transcend a typical author-editor relationship, if there is such a thing. The first thing she said to me, when we were face to face at last, was, “I thought you would be plump!” “And I thought you would be old,” I blurted out. Well, I wasn't plump, and Olive Ann certainly didn't seem old. In fact, she was beautifulâtall and slender, with enormous brown eyes and curly dark hair. She wore red lipstick and a silvery blue dress, long dangly earrings and a sparkly necklaceâand, underneath it all, flat sensible shoes.

Surely our friendship was an unlikely one. I was a novice, a twenty-five-year-old editor from New Hampshire, making my way in New York City. She was a born storyteller from the Deep South who was about to publish her first novel at the age of sixty. I knew just a bit more than she did about how books get published, and she knew far more than I did about the things that really matterâlife and death, for example. While I helped her cut some two hundred pages out of her manuscript, she taught me lessons that have helped determine the course of my life. We discussed punctuation, publicity, and print runs, of course, but we spent more time talking about husbands and children, the books we loved and the ones we didn't, the secret of a tasty casserole and the key to happiness on this earth. At times I provided her a link to the publishing process that she found so fascinating and so much fun; at other times, she offered me motherly advice, shared stories about her next-door neighbors or distant ancestors, and brought me up to date on the goings-on in her family. Always, she was an inspiration to me in her ability to see the humor, and even the joy, in any situation.

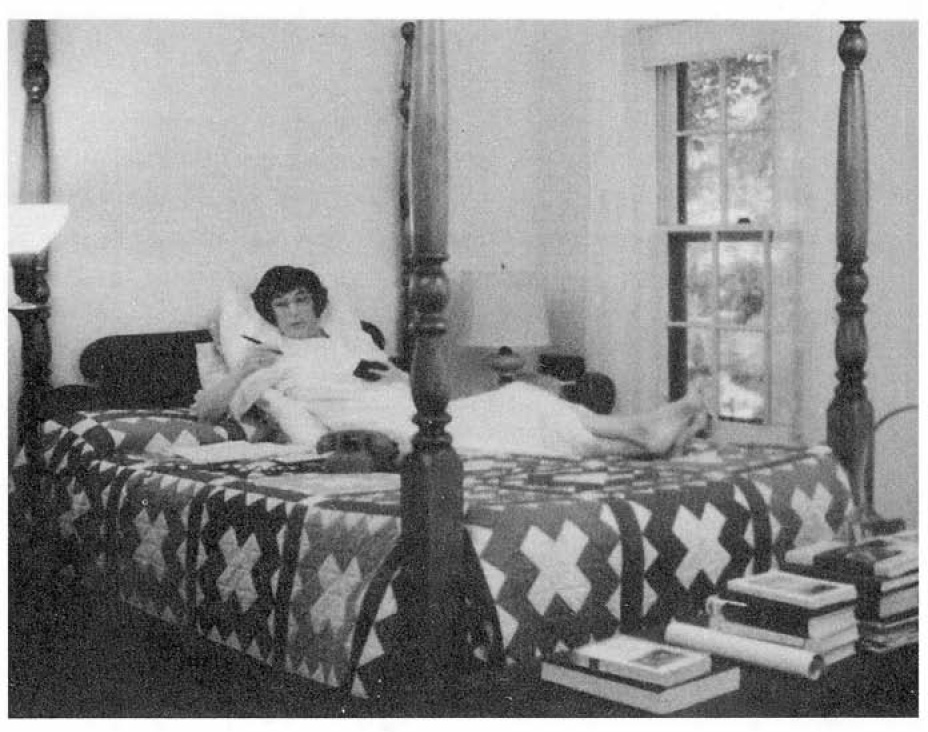

Olive Ann battled cancer on and off for ten years and spent the last three years of her life confined to bed with congestive heart failure. And yet, in the midst of her illness, she was able to look back on the previous year, a year during which she had left the house exactly twiceâonce to vote, and once to see the fall leavesâand say, “This has been a happy year.” She joked about someone who had referred to her bedridden condition as her “life-style,” as if it were something she had chosen. But she took issue with another friend, who had tried to sympathize with her “horrendous ordeal.” “I'm not trying to be brave or put a happy face on it,” she wrote, “but it has not been horrendous. Working on

Time, Dirt, and Money

gives structure to my days, and so many friends keep me integrated with the outside world.” Knowing that she would probably spend the rest of her life in bed, hooked up to an IV tube, Olive Ann never felt sorry for herself, and her enthusiasm for writing never waned.

She worked on the novel for almost five years, years during which she also had to cope with the demands of fame, with a recurrence of cancer and debilitating rounds of chemotherapy, and finally with the death of her beloved husband, Andrew Sparks, following his own long battle with cancer. Given the obstacles she confronted, it is a wonder she was able to work at all.

As readers of

Cold Sassy Tree

may know, the irrepressible character of Will Tweedy is based on Olive Ann's father, William Arnold Burns, who was fourteen years old in 1906, when the events in the novel take place. In

Time, Dirt, and Money,

Olive Ann introduces us to Will ten years later, and to the young woman he is about to marry, Sanna Maria Klein, who is based on Olive Ann's mother. The novel was to be the story of her parentsâof how they met, fell in love, and raised a family during the Depression. Above all, it was to be a portrait of their marriage, a marriage that was nearly destroyed by poverty, disillusion, and disappointment, but that survived and flourished again, years after both husband and wife had all but given up on finding happiness together.

Time, Dirt, and Money

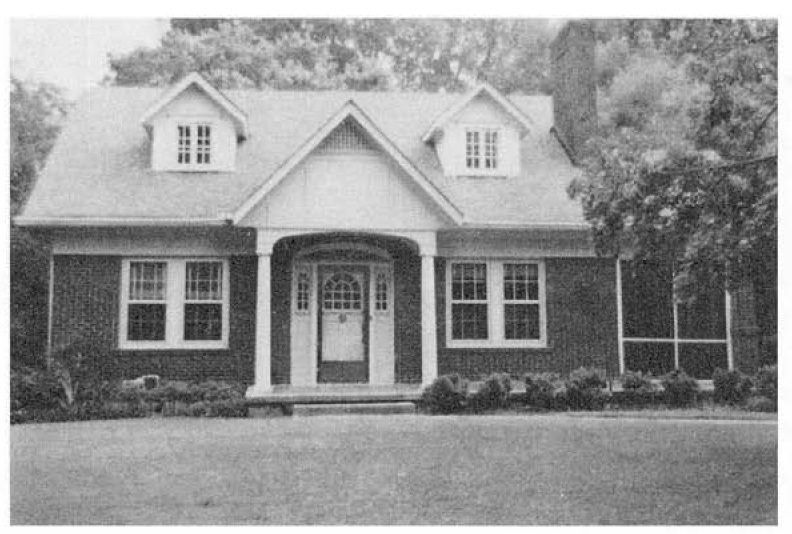

was due to be delivered to Ticknor & Fields on January 1, 1991. Olive Ann knew she wasn't going to make the deadline, but she always believed that she would finish the book. During the last years of her life, she so perfected the art of being both sick and productive that it was hard to imagine she wouldn't always be there, in her bed at 161 Boiling Road, a lacy afghan over her legs, a basket of letters to answer at her side, a Dictaphone or a pen in her hand. Andy once said that Olive Ann could be sicker than anyone else ever was, and he was right. But she had been desperately ill, and had pulled through, so many times that the news of her death, on July 4, 1990, came as a shock. She had just been talking about

Time, Dirt, and Money,

and I'm sure that her dying surprised her as much as it did everyone elseâjust as becoming a published author had surprised her. “I always thought selling a book was rather like dying,” she once said, “something that happened to other people, but never to me.”

Even now, as I read through the chapters published here, it's hard to accept that there are no more to come. Illness may have slowed Olive Ann down, but it never stopped her imagination or dulled her passion for storytelling. Months might go by, but then there would be another letter, full of funny anecdotes and wisdom. And there would be another batch of chapters to read after any long silence, miraculously produced through her painstaking process of jotting notes by hand, dictating, editing, and rewriting. (She never sent anything that was less than perfectâand she could never resist the urge to pick up her pen and start improving an impeccably typed page.)

Only during her final hospitalization did it occur to Olive Ann that she might not live to finish her book. Sometime after midnight, on June 22, 1990, she dictated a letter to her close friend and neighbor Norma Duncan, who had transcribed all the tapes for

Time, Dirt, and Money.

If she couldn't finish the book, she said, she hoped that the chapters she had already written would be published. Olive Ann was thinking of all those readers who wanted to know about Miss Love's baby and how Will Tweedy turned out. She had promised them a sequel, and she didn't want to let them down. This book, then, is Olive Ann's gift to her readers, and it is one way of saying good-bye, both to her and to the unforgettable characters she created.