Read Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents Online

Authors: Minal Hajratwala

Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents (25 page)

Thakor ("Tom"), standing, with his father, Ratanji, in the Narseys office in Fiji, ca. 1960s.

The Narsey family in Suva, 1962 or 1963. The unmarried sons are wearing printed Fijian "bula" shirts (back row: Bhupendra, second from left, and Manhar, third from right). The married sons and the sons-in-law are wearing suits (back row: Ranchhod, third from left, holding baby, next to his wife, Manjula; second row: Chiman, third from right). Ratanji and Kaashi are at center.

The Narseys Building in 2001: still a downtown Suva landmark, but the family business has been shuttered for two decades.

My mother, Bhanu (left), with school friends in Fiji, ca. 1960.

My father, Bhupendra, being seen off by his mother at the docks, 1963.

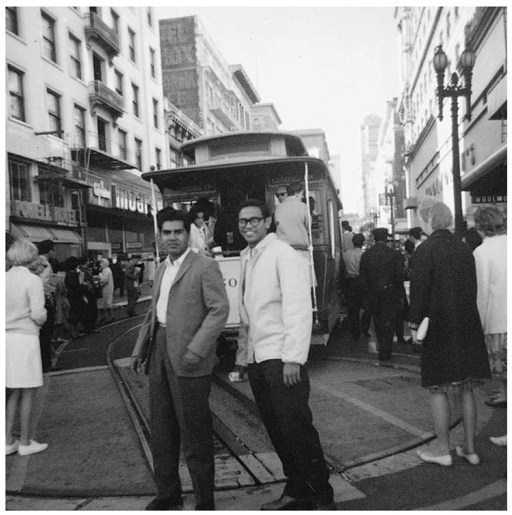

ABOVE

:

Bhupendra and Champak sightseeing upon their arrival in San Francisco, 1963.

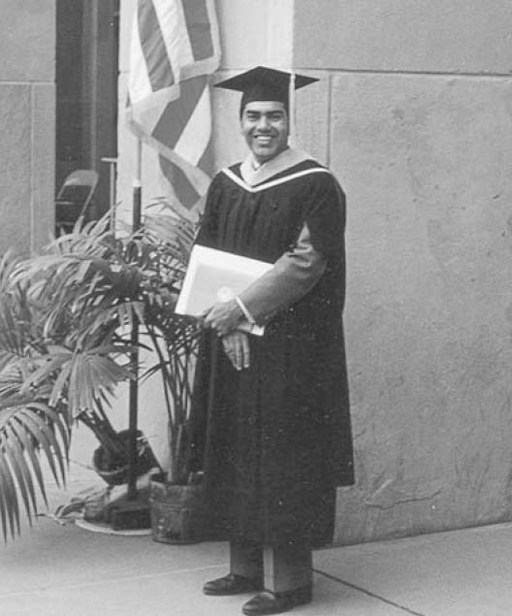

RIGHT

:

Bhupendra graduated with a master's degree in 1965. His father made multiple copies of this photo and sent it to all the family.

1984

Estimated size of the Indian diaspora: 4,599,063

Countries with more than 10,000 people of Indian origin: 33

1. South Africa

2. England and Wales

3. Guyana

4. Trinidad and Tobago

5. USA

6. Fiji

7. United Arab Emirates

8. Canada

9. Singapore

10. Surinam

11. Saudi Arabia

12. Oman

13. Netherlands

14. Yemen (PDR)

15. Kenya

16. Kuwait

17. Tanganyika

18. Qatar

19. Bahrain

20. Muskat/Muscat

21. Iraq

22. Zambia

23. Mozambique

24. Iran

25. Indonesia

26. Thailand

27. Australia

28. Nigeria

29. Germany (FRG)

30. Hong Kong

31. Jordan

32. New Zealand

33. Libya

We have built universities, technological institutions, and national science laboratories but they are emptier than before because they are constantly being drained ... Indeed, our entire educational system has become a big liaison and passport office.

—"India," paper presented at an international conference on the "brain drain," August 1967

I

N THE SUMMER

of 1963, my mother and father stood a few feet apart on the same dock, gazing up at the same ship. The

Oriana

was a gleaming white ocean liner about to embark for the western coast of North America, thousands of miles across the pure blue thrash of the Pacific.

They did not know each other, yet.

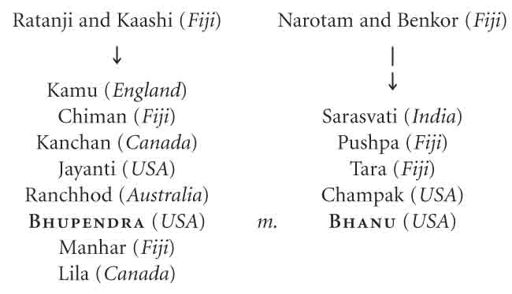

My father, Bhupendra, twenty-one years old, was traveling from Fiji to the New World to study. My mother, Bhanu, age sixteen, was at the dock to see her brother off. The two young men were the first of their community to go to the United States for education. Their fathers were friends and drinking buddies; over casual conversation, each had made the decision—despite some reservations—to buy his son one-way passage. And both mothers were on the verge of weeping.

As the families said their farewells, only a tiny hint of the future could be heard, a stage whisper from my mother's elder sister to their brother:—Keep an eye on that young man; I think he will be good for Bhanu.

And so my mother glanced at my father for the first time.

She noticed his loose-fitting pants, how he kept calling to his mother, pointing out to her various features of the ship:—Ma, look at this, he said,—and this, Ma, and this.

—Isn't he nice-looking, my mother's sister said, nudging her.

—Maa! Maa! my mother mocked, bleating like a sheep. She was still in high school, a popular girl, star student, and basketball center; her mind was not on marriage. As she watched her brother and her father's friend's son disappear up the gangplank, she had no idea that this stranger would become the most important man in her life.

I imagine the very beginning of each of my parents' lives, long before they converge: egg and sperm meeting, dividing, differentiating, a bundle of human tissue hurtling toward human being. In the third week after conception, before either of my grandmothers even knows she is pregnant, a certain layer of cells known as the ectoderm begins to thicken. This is the beginning of neural development: what will become the brain.

My father's brain, my mother's brain. By the time of birth, eight and a half months later, it is doing everything it will ever do—controlling bodily functions, taking in sensations, learning. According to the Enlightenment philosophers of Europe, it is a tabula rasa: a blank slate awaiting mathematics, morality, language; a repository of free will. In the Hindu understanding, it is the reincarnation of an ancient karmic stream already destined to grow, migrate, and make me.

As Bhanu and Bhupendra grew up, their brains became more than their individual organs. Among the most educated young people ever produced by their community, they migrated in their twenties from the Third World to the First. The leap was momentous, not only for them and their future children, but also because it was part of a worldwide pattern so remarkable that it developed its own experts and statistics, its own terminology: the brain drain.

Coined in 1962 to describe the large-scale migration of skilled technocrats from Britain to the United States, the term was quickly co-opted to describe a related, even more dramatic phenomenon: the movement of educated professionals from developing countries, particularly India and China, to developed nations, particularly the United States. Critics saw the brain drain as a large-scale theft by the world's wealthiest nations of the intangible assets of countries that could ill afford to lose their brightest young people. Apologists defended what they saw as merely the free market at work. "Brains go where money is," argued one, while, in the version preferred by

Science

magazine in 1965, "Brains go where brains are ... where there is a challenge ... where brains are valued." Thousands of articles and books, hundreds of thousands of academic and conference hours, and even several rounds of hearings before the U.S. Congress and the United Nations were devoted to various aspects of the brain drain: solutions to the problem, if it was a problem; analysis of the statistics, laced with regret that better statistics were not available; and purported calculations of the lost value to its native country of each "drained" brain (estimates ranged from $20,000 to $75,000). My parents' brains, and those of millions of others who migrated during the 1960s and '70s, were no longer their individual properties alone; they were commodities for the West.

At root, the experts wanted to know what I, child of such migrants, also wonder: How did these men and women, crème de la crème, come to travel from one world to the next? And why—despite their deeply rooted histories, despite the difficulties of exile, and even sometimes despite themselves—did they stay?