Lee Krasner (22 page)

Authors: Gail Levin

Krishnamurti may well have appealed to Pollock after growing up in a family that did not attend church and with parents who professed no spiritual beliefs. In contrast, Krasner had grown up in a religious family and rejected most of the ritual of Orthodox Judaism along with the patriarchy that she felt oppressed women. But she remained intellectually curious about religious practices and retained some of the fears associated with folk beliefs imported by her mother from the shtetl.

In 1930 Jackson followed the example of his eldest brother, Charles, who had chosen to study art. Like Charles, who moved to New York in 1926 and enrolled in the Art Students League in the class of the muralist Thomas Hart Benton, Jackson too joined Benton's class. Though Pollock studied with Benton, who painted representational images that came to be called “regionalist,” and Krasner studied with Hofmann and painted modernist abstractions, the two had had some similar aesthetic experiences. Like Krasner, Pollock had worked on WPA murals, though he

soon transferred to the easel division. Pollock had worked on a mural for Grover Cleveland High School under Job Goodman, the same former Benton student with whom Krasner had studied drawing.

117

So it must have seemed to Krasner as if they had much in common despite their divergent ethnic backgrounds.

The summer that Krasner met Pollock, his brother Sande (Sanford), with whom he had been living in New York, had written to their oldest brother, Charles, then in Michigan working on murals and graphic art for the WPA, and said that Jackson's maladjustment had proven to be much more than “the usual stress and strain of a sensitive persons [

sic

] transition from adolescence to manhood, a thing he would out-growâ¦. One requiring the help of Doctors. In the summer of 39 [1938] he was hospitalized for six months in a psychiatric institution. This was done at his own request for help and upon the advice of Doctors.”

118

Sande lamented that though Jackson had shown improvement upon release, it did not last, and they had had to seek medical attention again. He worried about Pollock's alcoholism and his self-destructive nature and warned that “part of his trouble (perhaps a large part) lies in his childhood relationships with his Mother in particular and family in general.” Sande reported to Charles on Jackson's condition, referring to one of his symptoms as “depressive mania (Dad).”

119

Despite his brother's psychiatric problems, Sande had also studied art, and he asserted that Jackson's art “if he allows [it] to grow, willâ¦come to great importance.” Sande believed Pollock was “doing work which is creative in the most genuine sense of the word. Here again, although I âfeel' its meaning and implication, I am not qualified to present it in terms of words. His thinking is, I think, related to that of men like Beckmann, Orozco, and Picasso. We are sure that if he is able to hold himself together his work will become of real significance.”

120

But Krasner was still unaware of most of Pollock's problematic history. Only later did she learn that Pollock was in analysis,

which she recalled, “I was very shocked to learn, because I was very prejudiced, couldn't have been more against it, so that I had a conflict in response, that is, there was full response to the painting, later learning he is in analysis I was very unsympathetic to that.”

121

But for now, she needed a man in her life again; it was wartime, and Pollock seemed to fit the bill. She immediately began to consider the possibilities.

Had Krasner known all of what the family knew, perhaps she would have backed away from Pollock. B. H. Friedman wrote in 1965, “The answers to some of Rimbaud's questions were there in this rangy handsome tough-tender rebellious Westerner. Lee had met someone to whom she could âhire herself out,' a beast whom she could adore.”

122

Had she asked her friend George McNeil, she might have gotten a more realistic impression. “Jackson was very macho from the beginning, drinking being the big thing,” McNeil reported. “Behavior at the [Art Students] League could be pretty far out; you could be drunk in the lunchroom, loud, all kinds of things; and there were Saturday night bouts at 125th Street in Harlem. I remember the folds in his face and the way he

felt

bigâstrong and tough. He came on like a big guy, and his walk seemed a kind of shuffleâa wobbling walk, not direct.”

123

But Krasner did not ask her friends what they thought of him. Nor would she have been dissuaded by knowing that, according to McNeil, Pollock was “shy, hated crowds, would go to the rooms with no one in them at shows and didn't like openings.”

124

Pollock soon visited Krasner's Ninth Street studio, and she felt that his initial response was “very sympathetic.”

125

What he saw were the paintings inspired by Picasso, work of the late 1920s, forms with heavy black outlines derived from still life setups and intense primary colors that recalled the work of Mondrian. Her paintings were also reminiscent of Gorky's adaptations of Picasso's work. Since by then Pollock too was also deeply engaged with Picasso, the two found common ground.

Mercedes Carles Matter recalled, “Lee dropped in one day to

tell me she had met someone she liked very much. They were to have their first date that afternoon, to go to the Frick Collection together.”

126

Krasner was smitten. She soon brought Pollock to meet Mercedes and Herbert, who later recalled: “From the first time I met himâin 1941â¦from that very first evening Jackson and I felt a deep rapport.”

127

Both introverts, Matter and Pollock seemed to have hit if off without much conversation; they felt no need for small talk. De Kooning recalled that Matter and Pollock “were taken with each otherâthey had a nice feeling between them. They didn't have to talk.”

128

Krasner was also the one who introduced Pollock to de Kooning. She told Pollock about another artist who would also be in the show with them and took him over to meet de Kooning at his loft. She later recalled: “De Kooning had a loft at that time because he was something.”

129

The fact that Krasner chose to take Pollock to meet de Kooning suggests that she believed that the Dutch painter respected her and her work. She was part of “the gang” during the 1930s. According to Emilie Kilgore, who was close to de Kooning in the 1970s, he remarked that Krasner “was no slouch as a painter.”

130

Krasner had already lived with Pantuhoff's excessive drinking, which may have misled her to suppose she could handle Pollock's. But she could hardly have foreseen Pollock's tendency to “be violent when he was drunk,” as his sister-in-law Arloie McCoy would later describe it. The artist Mervin Jules concurred that Pollock “got mean when he was drunk,” but no one warned Krasner.

131

Alma, the wife of Pollock's brother Jay, saw that Pollock “wanted his life to be free to paint. In order to do that, others had to do everything else. And he didn't want to be helped; he wanted to be taken care of.”

132

Taking care of a man, especially one she viewed as destined to make art history, did not strike Krasner as too steep a price.

Regardless, some of Krasner's contemporaries believed the price was too steep, and that it affected Krasner. For example,

Fritz Bultman incorrectly claimed that Rimbaud's words first appeared on Krasner's wall only after she met Pollock. “Lee was quite excited about Jackson, having written in great big blue script on her wall as a way of anticipating their life together, a part of Rimbaud's

Season in Hell

about worshipping the beast and so forth, and Jackson was certainly an âinfernal bridegroom.' But he was very lonesome and warm underneath his not knowing how to make contact with people. The alcoholic macho thing was a mask; he needed a breakout from time to time.”

133

One of Mercer's letters from September 22, 1941, refers to the Rimbaud words on the wall, so Bultman cannot have accurately remembered when Krasner put the writing on her wall. Krasner also recalled clearly on separate occasions to Friedman, Munro, and others that the words were written in black with only one phrase, “What lie must I maintain?,” written in blue.

134

Krasner told Friedman in 1965 that the words by Rimbaud were there on her studio wall “through the late thirties and early forties”

135

There was even a notable instance involving Bultman and the wall before Krasner met Pollock. When Bultman brought the playwright Tennessee Williams to Krasner's New York studio, the Rimbaud quotation on the wall proved provocative. According to Krasner, Williams “pulled apart” the Rimbaud quotation in such an offensive manner that she asked him to leave.

136

This probably took place a year or so before Krasner encountered Pollock.

Even if, as Bultman claimed, Rimbaud's words had not appeared on Krasner's walls until after she started seeing Pollock, it is fair to say that they also characterized her relationship with Igor, who had both his own internal demons and his sense of inadequacy that he could not seem to measure up to his parents' high expectations. The Pantuhoffs desperately wanted their sons to regain some semblance of their own lost position in societyâto marry upâcertainly not to the daughter of poor Jewish immigrants from Russia.

In this portrait of Lee Krasner by Igor Pantuhoff, he seems to have captured how she responded to the stress of the Depression, his infidelities, and the general insecurity of their lives. Private collection; photograph courtesy of the Pantuhoff Family Collection.

With regard to the new couple, Bultman commented, “He and Lee complemented each other, but it was almost like an antagonism.”

137

This contrasts with the experience of John Little, who later recalled that in late 1941, “Lee was in charge of the Works Progress Administration. One evening she invited me to her studio to meet and take a look at the work of a young painter who was also on the WPA by the name of Jackson Pollock.” Little remembered that she was “very enthusiastic about” Jackson and that he too thought the pictures were “very exciting and beautiful. Later that week we met Jackson [Pollock] himself at her studio. On that occasion he was very silent and shy: once in a while a smile would light up his face but no words came.”

138

Balcomb Greene, who was also on the Federal Art Project with Krasner, Pollock, and Little, when asked with whom he worked, said, “Lee Krasner is about the only one I can recall.”

139

For

Greene as for many others, Krasner stood out. Like her, Greene had also joined the Artists Union and the American Abstract Artists. He worked on abstract murals for the World's Fair in 1939 and for the Williamsburg Housing Project. Krasner recalled Greene too, but with a host of other colleagues from the WPA.

140

By early December 1941, Krasner's friends all noticed something new. Even from afar, Mercer wrote to Krasner, anticipating a visit with her in New York. After he had not heard from her, he wrote again, asking, “Why so silent?â¦I believe something is up with you. Out with it!” His visit had been postponed, and he would see her after his family at the end of his leave. “Krasner, I must talk with you even if you are married to someone else.”

141

He looked forward to dancing with her too.

142

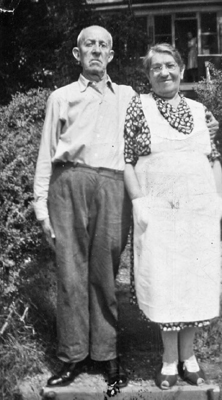

Krasner family photograph before their emigration in Shpikov, the Russian Empire, c. 1905, three years before Lena's birth. In this photograph, the edge of the imaginary painted landscape is visible, which must be one of the first painted scenes that Lee Krasner ever saw.

Joseph and Anna Krasner, Huntington Station, Long Island, c. 1936. After nearly two decades of physical drudgery and economic uncertainty as fishmongers in Brooklyn, Joseph and Anna had moved to Huntington, Long Island, which afforded a small-town life like the one they had in Shpikov.

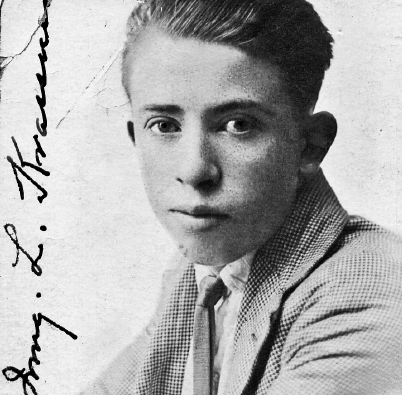

Lena Krasner (front row, sixth from left) at her graduation from Brooklyn's P.S. 72, 1921. She walked to this public school from the family's rented house on Jerome Street in East New York, on central Brooklyn's eastern edge, where she recalled that it was “Rural. Not a city.”

Irving Krasner, Lee's only brother, introduced her to culture: he went to the library and brought home books by the great Russian authors, and probably read aloud to Lena from the English translations.

At the National Academy, Krasner became especially close to the Mirsky sisters. Kitty, the older sister, painted dark and brooding seascapes and kittens, while her sister Eda preferred flowers and children in warmer colors and sensuous shapes.

Eda Mirsky (Mann), Krasner's classmate at the National Academy, was so frustrated by the sexism that years later she discouraged her daughter Erica Jong from pursuing a career in the visual arts.

Eda Mirsky (Mann),

Portrait of Lee Krasner

, c. 1929â30, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Krasner's classmate portrayed her as a stylish flapper. The two women were briefly suspended from the Academy after they went to the school's basement to paint a still life of a fish, which was forbidden for women. Gift of Eda Mirsky Mann, 1988.

Esphyr Slobodkina,

Lee Krasner Astride a Fighting Cock

, 1934, Crayon sketch on manila paper for a large cartoon to decorate the artist and model's costume ball. Using the obvious sexual metaphor of a female paper doll astride a cock, this sketch caught the sexual electricity in Lee Krasner's relationship with Igor Pantuhoff. It shows Krasner as a triple threatâas three female figures, repeated as if in a cubist painting or film, mounted on a rooster's back. Courtesy of the Slobodkina Foundations, Glen Head, New York. Photograph by Karen Cantor.

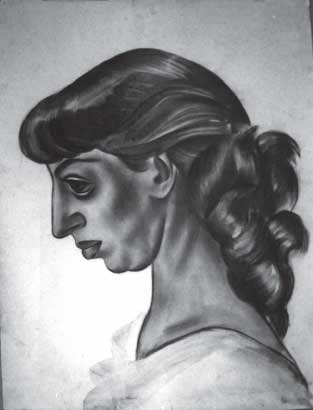

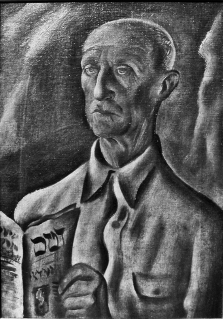

Igor Pantuhoff,

Portrait of Joseph Krasner

, c. 1936, Igor, who often visited Lee's home, probably took a photograph of Krasner's parents and used it to paint this portrait of her father, showing him holding a Yiddish book. Collection of the Pollock-Krasner House.

Igor Pantuhoff,

Portrait of Lee Krasner

, c. 1932, gouache on paper, 22 x 25. Judging simply from this sketch Pantuhoff did of Krasner posing in a sultry profile, he responded to the sex appeal that some of her contemporaries remarked upon. “With Igor, Lee had a sparkle and gaiety,” said Fritz Bultman. Collection of the Pollock-Krasner House.

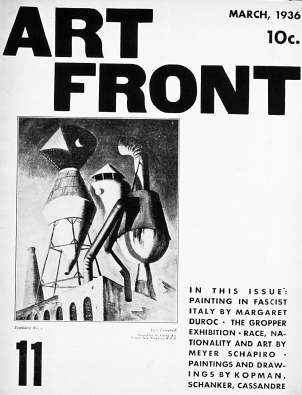

Igor Pantuhoff,

Ventilator #1

, reproduced on the cover of

Art Front

, March 1936. Painted for the Federal Art Project, Pantuhoff's composition and subject matter, depicting the rooftop of an urban building with water towers and chimneys, were quite close to Krasner's painting

Fourteenth Street

of 1934.