Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business (32 page)

Read Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business Online

Authors: Ronald Weitzer

Tags: #Itzy, #kickass.to

Figure 6.5. Ria’s Men’s Club.

Figure 6.6. Jan Bik.

The brothels just described are located outside the city’s three windowed red-light districts. I now describe the social organization and atmosphere in the three zones, based on my field observations and other sources.

The Red-Light Districts

A 1995 survey reported that about one-fifth (22 percent) of Dutch men had bought sex from a prostitute at some time (no comparable recent data exist).

124

In addition to these Dutch clients, a substantial proportion of clients in the Netherlands are foreign tourists. In a survey of 94 window workers in Amsterdam, 12 percent stated that most of their clients were tourists, 18 percent said that most were Dutch, and the remaining 70 percent said they serviced both equally.

125

No comparable data exist for other venues, but Dutch clients are more likely to visit brothels and clubs outside the red-light districts. As I indicated in

chapter 5

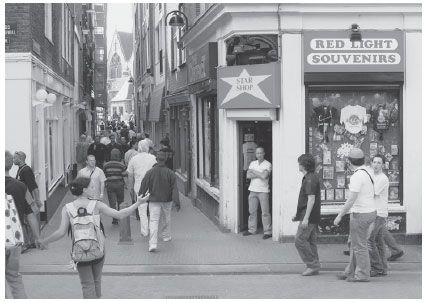

, Amsterdam hosts far more tourists (and thus potential sex clients) every year than do Antwerp and Frankfurt—twice as many as the two other cities combined. Coupled with the sheer number of visitors is the fact that Amsterdam’s main red-light district is in the heart of the city, whereas Antwerp’s and Frankfurt’s RLDs are some distance from the city center. This means that far more people encounter Amsterdam’s sexual marketplace—visitors who range from those who find the red-light area

an amusing tourist attraction to heavy partiers to seekers of titillating “eye candy” or sex. Both the sheer number of people on the streets and the fact that a significant number of them are intoxicated increases the potential for disorderly behavior, altercations with sex workers, and complaints from local residents. These problems make Amsterdam’s main RLD more susceptible to adverse media attention and politicization than its red-light counterparts in the two other cities.

Amsterdam has three separate red-light districts: a large one in the city center (the Wallen, with about 300 windows), one in the Singel area (with about 70 windows), and one in Ruysdaelkade near the city’s cultural gem, the Rijksmuseum (about 40 windows).

126

The number of window workers exceeds the number of windows because workers typically work for one shift and rotate with one or two others. The most recent census reported that a minimum of 570 window prostitutes were working on any given day and that the number exceeding the minimum fluctuated during the year.

127

The census also found that half the window workers in the Wallen were aged 18–26 and more than half were of eastern European background, especially Hungarian.

Singel’s RLD is located in a mixed commercial-residential area, while Ruysdaelkade is largely residential. Both areas cater to local Dutch clients primarily, and most tourists are unaware of them. The downside for workers is the small customer pool compared to the central RLD, which is teeming with people. According to a Ministry of Justice official I interviewed, the two small window areas are not a source of problems.

128

These small RLDs are tranquil spaces. Moreover, their very existence in residential areas and the involvement of Dutch clients suggests that window prostitution is part of the city’s local culture and not just a tourist attraction. The Singel area hosts several Dutch providers who are rare in and older (30–50 years of age) than is the norm for the main RLD in the Wallen.

It is useful to describe the three red-light landscapes in some detail, as their structure and ambience influence the views and experiences of local residents, visitors, workers, and clients. Singel’s RLD is depicted in

figures 6.7a

and

6.7b.

My fieldnotes describe it as “a well-kept area, not run-down, not seedy.”

129

There is graffiti along one street (Nieuwstraat) but otherwise no signs of decay. Window rooms on Nieuwstraat are away from the shops in the area, whereas the few windows on Spuistraat are nestled among residences, snack bars, a few hotels, one marijuana cafe, and some bars. A large church, the Dominicus Kerk founded in 1893, stands just a few feet away from some of the window rooms. There are no other sexually oriented places in the area,

aside from a gay sex shop/cinema. About 25 women were working during the days I visited. One afternoon, I spent two hours observing the street scene from a perch in a cafe just a few yards from a row of windows. Nothing eventful was observed, and the atmosphere was placid. People walked by the windows, occasionally stopping to chat with a worker. On a return visit ten months later, in March 2011, I conducted observations from the same location, captured in my fieldnotes:

There is a steady flow of people walking along the street, on bikes, and some cars passing through. Men carrying briefcases walk by, and a couple with two very young boys stops right in front of one of the occupied window units, to tie the boy’s shoes. About one-third of the pedestrians are women. The street scene is very similar to any other mixed commercial-residential area of Amsterdam, with the window women on Spuistraat attracting little attention. Men walk by and look at the workers, but few stop to talk to them. During my three hours of observation of two windows across the street, only one woman got any inquiries from men (four times), and only one man entered her room, emerging 30 minutes later. These two women sit on their stools almost the entire time, talking on the phone, and they make no attempt to “perform” to entice men inside.

I asked the two baristas in the cafe, “What is it like having your shop so close to window prostitution?” They replied, “No problem. We’ve gotten along fine for ten years, since we’ve been here. Here, there are many kinds of places—a church, [marijuana] coffee shop, gay cinema, prostitution—and this area is tolerant of such diversity.”

130

They seemed surprised by my question, and their answer was rather nonchalant. Clients who contribute to online message boards describe Singel’s atmosphere in similar terms. One compared Singel to the larger, main RLD in the city center:

I’ve been visiting Singel a lot more recently. I like the relaxed attitude of the girls there. They seem to have fewer restrictions than the girls in the Wallen and time [with a client] never seems to be an issue. I’d also be very surprised if there are any rip-offs there. But it really is hit and miss [as] to who is working, a really mixed bag. Sometimes there are some young and really pretty girls and sometimes quite the opposite.

131

Another client agrees that Singel is “much more appealing [than the Wallen] for relaxed situations and rip-off free.”

132

Figure 6.7a. Spuistraat, Singel red-light district, window rooms on the left.

Figure 6.7b. Nieuwstraat, Singel red-light district.

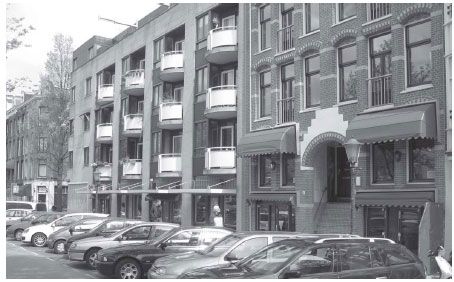

Ruysdaelkade’s RLD is even smaller than Singel’s and is fully residential, as shown in

figure 6.8

. A few shops border this RLD, but they are not interspersed among the windows as in part of Singel. Like Singel, in Ruysdaelkade, I observed no one loitering, no disorderly people, and none of the festive and sometimes raucous “vice scene” that characterizes some red-light districts. I observed fewer people on the street than in Singel, because of Ruysdaelkade’s residential nature. There are no tour groups visiting the two small RLDs because they lack the circus atmosphere of the Wallen. If not for the red lanterns and neon lights and women sitting behind windows, these areas would be indistinguishable from any other Dutch neighborhood.

Figure 6.8. Ruysdaelkade red-light district.

Figure 6.9a. The Wallen red-light district. Oude Kerk appears in the background.

Amsterdam’s main red-light district in the Wallen differs radically in social ecology and ambience from the two small RLDs just described and from those in other Dutch cities and in Antwerp and Frankfurt. Each place looks and feels quite different to the visitor. Recall that Antwerp’s is a tidy, quiet, single-purpose, pedestrian-only setting, while Frankfurt’s main RLD is multiuse and crisscrossed by streets with vehicles passing through. In Amsterdam, the congested Wallen area sees few cars along its single-lane canal roads and none along the windowed alleys.