Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business (4 page)

Read Legalizing Prostitution: From Illicit Vice to Lawful Business Online

Authors: Ronald Weitzer

Tags: #Itzy, #kickass.to

Many of the writings in the oppression paradigm feature quotations from a few sex workers, typically the most disturbing stories presented as indicative of intrinsic problems. Gayle Rubin has criticized an earlier generation of oppression writers for cherry picking the “worst available examples” and casting them as representative.

71

If these authors comment at all on findings that they did not expect, they go to great lengths to discredit such findings. Particularly inconvenient are those sex workers whose experiences clash with the author’s views. Raymond writes, “There is no doubt that a small number of women

say

they choose to be in prostitution, especially in public contexts orchestrated by the sex industry.”

72

But the number is “small,” and

her emphasis on the word “say” and her use of “orchestrated” casts doubt on the veracity of the women’s testimony. Prior to interviewing a few workers in Nevada’s legal brothels, Farley stated, “I knew that they would minimize how bad it was.”

73

If the respondent did not acknowledge that working in a brothel was “bad,” she was in denial, and Farley sought to penetrate this barrier: “We were asking the women to briefly remove a mask that was crucial to their psychological survival.”

74

She also asserts that “most” of the women working in the legal brothels had pimps, despite the fact that the women were “reluctant to admit that their boyfriends and husbands were pimping them.”

75

And “a surprisingly low percentage” of the women said that they had been sexually abused as a child, which Farley dismisses as being “lower than the likely actual incidence of sexual abuse.”

76

In Farley’s study of six countries, she found substantial support for legalization of prostitution: a majority (54 percent) of the prostitutes interviewed across the countries (and 56 percent in Colombia, 74 percent in Canada, and 85 percent in Mexico) said legalizing prostitution would make it safer.

77

These inconvenient figures are presented in a table but are not discussed in the text (Farley simply says that 46 percent of the total did not believe legalization would make prostitution safer). In another article, Farley discounts those who favor legalization: “Like everyone else, our interviewees minimized the harms of prostitution and they sometimes believed industry claims that legalization or decriminalization will somehow make them safer.”

78

Workers who want legalization apparently could not have formed this opinion on their own and must have been deceived by advocates.

When oppression writers comment at all on findings from other studies that clash with their paradigm, these findings are discounted, reinterpreted, or inverted.

79

Most of the time, however, these writers simply ignore findings that challenge their claims. Karl Popper, the renowned philosopher of science, described

prescientific reasoning

as conclusions formed in the absence of evidence or lacking in the critical ingredient of falsifiability.

80

As should be abundantly clear by now, the oppression paradigm is first and foremost a prescientific ideology. Its central tenets are not derived from carefully conducted research, which would contradict or radically qualify those very tenets. In short, the oppression paradigm pays little heed to the canons of scientific objectivity, and this is due to its advocates’ overriding commitment to abolishing sex work.

Popular in some academic circles, the oppression framework also predominates in the media, in political discourse, and in policymaking in many countries. The mass media are saturated with stories highlighting worst cases,

and news reports usually center on themes of violence, pimping, crime, disease, and immorality.

81

Government officials in most of the world view prostitution through the same lens. The oppression paradigm is occasionally questioned, however. In the debates on a legalization bill in the parliament of Western Australia in 2007 and 2008, the ruling Labor Party systematically critiqued the assertions of a prominent oppression writer (Janice Raymond) and voted to legalize prostitution because of its harm-reduction potential.

82

And in a recent successful challenge to the constitutionality of Canada’s prostitution laws, the court downgraded the testimony of three antiprostitution witnesses (Melissa Farley, Janice Raymond, and Richard Poulin) because of their biases.

83

These two examples demonstrate that on rare occasions state officials have rejected the dominant oppression frame and the claims of its advocates.

The Polymorphous Paradigm

Both the oppression and empowerment paradigms are one-dimensional and essentialist. While exploitation and empowerment are certainly present in sex work, there is sufficient variation across time, place, and sector to demonstrate that sex work cannot be reduced to one or the other. An alternative, what I call the

polymorphous paradigm

, identifies a constellation of occupational arrangements, power relations, and participants’ experiences. Unlike the other two perspectives, polymorphism is sensitive to complexities and to the structural conditions shaping sex work along a continuum of agency and subordination.

84

The policy implications are clear: rather than painting prostitution with a broad brush, we can identify those structural arrangements that have negative effects and bolster those associated with more positive outcomes.

Because the complexities of the polymorphous model cannot be boiled down to sound bites, it rarely appears in the news media, popular culture, political debates, or public discourse. Consequently, the prostitution myths described earlier have become the conventional wisdom. But there are some exceptions in popular culture. In the first episode of the autobiographical Showtime television series

Secret Diary of a Call Girl

, a London escort tells the audience, “There’s as many kinds of working girls as there are people. So you can’t generalize.” And a few movies present prostitution in a richly nuanced or mixed manner rather than stereotypically.

85

A growing body of research documents tremendous international diversity in how sex work is organized and experienced by workers, clients, and third parties.

86

These studies undermine some deep-rooted myths about

prostitution and present a challenge to those who embrace monolithic paradigms. Victimization, exploitation, agency, job satisfaction, self-esteem, and other dimensions should be treated as

variables

(not constants) that differ between types of sex work, geographical locations, and other structural conditions. In the remainder of this chapter and in

chapter 2

, I present evidence in support of the polymorphous paradigm by contrasting different types of prostitution.

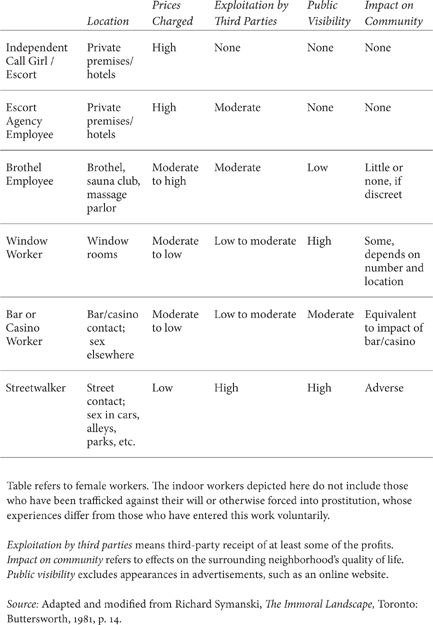

TABLE 1.1

Selected Types of Prostitution

Many historical studies of prostitution excel at describing hierarchies, as well as changes in sexual commerce over time.

87

Such historical diversity and change offers abundant counterevidence to grand claims about the “intrinsic” nature of commercial sex. Today, no less than in the past, prostitution is stratified. Prostitutes vary tremendously in their reasons for entry, risk of violence, dependence on or exploitation by third parties, experiences with the authorities, public visibility, number and type of clients, relationships with co-workers, and impact on the surrounding community. Age, appearance, and ethnicity also figure into the hierarchy, shaping workers’ earning power. And location is a key variable—with important distinctions between sex work conducted on the streets, indoors in a hotel or residence after an initial contact is made elsewhere (e.g., in a bar, karaoke club, restaurant, casino), and in indoor settings where both the initial contact and sex occur in the same place (e.g., brothels, massage parlors, saunas, hair salons, clubs). A hybrid type is window prostitution, in which workers operate indoors but are observable from outside. They are much more visible than are other indoor workers, but they are shielded from the street by their rooms. Window prostitution exists in two of the cities examined later in this book, Amsterdam and Antwerp, as well as in several other cities around the world.

Table 1.1

presents a typology of prostitution. In street prostitution, the initial transaction occurs in a public place (a sidewalk, park, truck stop), and the sex act takes place either in public or in a private setting (alley, park, vehicle, hotel, etc.). Many underage street prostitutes are runaways who end up in a new locale with no resources and little recourse but to engage in some kind of criminal activity—whether theft, drug dealing, or selling sex. They sell sex out of dire necessity (“survival sex”) or to support a drug habit. The process typically begins with bartering sex for food, drugs, or a place to stay and evolves into more routine sex-for-money exchanges. Some do this independently, but many underage prostitutes quickly become involved with pimps.

88

Street prostitution is associated with myriad problems. Many street workers use addictive drugs, work in crime-ridden areas, are socially isolated and disconnected from support services, engage in risky sex, are exploited and

abused by pimps, and are vulnerable to being assaulted, robbed, raped, or killed on the streets. By standing on the sidewalk, they are accessible to predators who seek to rob or attack them, as well as to voyeurs who shout insults and obscenities at them. Friction with local residents is also common. Those street sellers who are free of drugs and pimps have greater control of their work but still confront the occupational hazards just described.

89

The types presented in

table 1.1

are not rigid. An individual may fit into more than one category. For instance, independent call girls may also accept occasional appointments from an escort agency, and massage parlor or brothel workers sometimes moonlight by meeting customers in private and keeping the earnings for themselves. But it is rare for workers to experience substantial upward or downward mobility. As a rule, “the level at which the woman begins work in the prostitution world determines her general position in the occupation for much of her career as a prostitute. Changing levels requires contacts and a new set of work techniques and attitudes,”

90

and moving up often requires a level of health and attractiveness that many street workers lack. If a move takes place, it is usually lateral, such as from the street to a down-market peep show, from a massage parlor to an escort agency, or from an escort agency to independent work. Occasionally, an upper– or middle-tier worker whose life situation changes (e.g., because of aging or drug addiction) is no longer able to work in that stratum and gravitates to the street, and police crackdowns on indoor businesses can force some of these workers to the streets. But in general, indoor workers are not inclined to consider street work as an option.

91

Likewise, transitioning from street work to escorting or a brothel is quite rare. Most street workers lack the education and skills required for indoor work, insofar as it requires prolonged social interaction with clients; many would be rejected on appearance grounds by an indoor operator; and many street prostitutes would dislike working indoors because they would not see the “action” that they are accustomed to on the streets or because they would have trouble conforming to the myriad rules imposed on them by house managers.

92

What about the clients of sex workers? Earlier in the chapter, we saw how oppression-paradigm writers demonize “johns.” Yet the evidence shows that customers vary tremendously—in age, race, and social class; in their reasons for buying sex; and in their experiences during paid sex encounters.

93

Most do not fit the stereotype of the violent misogynist.

94

Sociologist Martin Monto concludes that there is “no evidence to suggest that more than a minority of customers assault prostitutes” and that “most clients do not hold views that justify violence against prostitutes.”

95

Only a fraction of arrested

customers have a previous conviction for a violent or sexual offense.

96

Some are indeed predators intent on acting violently, while others seek out the most vulnerable prostitutes because they feel they are easily controlled. But other clients are “repulsed at the idea of buying sex from prostitutes who are desperate, vulnerable, or coerced into prostitution” and say that if they met a trafficked victim, they would try to help her escape or contact the police.

97

On websites where clients recount their experiences and share information with others, it is “not uncommon for these writers to complain about violence against prostitutes or to encourage others to treat prostitutes with respect.”

98

Interestingly, the largest study of client interactions with call girls reported that in half these encounters the men played the subordinate role: they “enjoyed relaxing and letting the call girl direct the love play.”

99

Clients use their economic power to buy sex, but they do not necessarily enact domination in the course of their sexual interactions.