Legions of Rome (52 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

Many British nobles were equipped with captured Roman arms. And they had their chariots—small, light, open-ended, with wheels just 3 feet (30 centimeters) across, and drawn by a pair of nimble ponies. The design of the British chariot had not changed since Caesar encountered 4,000 of them during his 55

BC

campaign. The number fielded by Boudicca’s rebels is unknown, but they are unlikely to have been numerous, for there had been little time to build them and train chariot horses.

Boudicca herself appeared in a chariot, with her long, red-brown hair flowing.

[Dio,

LXII

, 2] “With her daughters before her” in the chariot, Boudicca galloped from one tribe to another to deliver pre-battle speeches. [Tac.,

XIV

, 35] Boudicca urged the warriors to die rather than live under Roman rule. She reminded them how they had punished the 9th Hispana Legion, and assured them that the rest of the Roman troops on the island were cowering in their camps and planning to flee. “Let us show them that they are hares and foxes, trying to rule over dogs and wolves!” [Dio,

LXII

, 5]

Against such massive odds of perhaps twenty-three to one, most Roman troops were only thinking of survival. Gnaeus Julius Agricola, a 19-year-old junior tribune on governor Paulinus’ staff this day, would later tell son-in-law Tacitus that “they had to fight for their lives before they could think of victory” in this battle. [Tac.,

Agr

., 5] Yet the Roman commander was confident of success. He too addressed his troops, riding to each of the three divisions. Paulinus’ speeches had a common core: “Close up the ranks, and having discharged your javelins, then with shields and swords continue the work of bloodshed and destruction.” [Tac.,

A

,

XIV

, 36]

And then the British chariots were lumbering forward. Celtic warriors advanced at the walk behind them, roaring out their battle cries. The Roman formations stood their ground, waiting. The chariots gathered speed. As they charged the Roman wedges, their passengers let fly with a volley of spears, which Roman shields parried. The legionaries then let fly with their first flight of javelins, then another. As Roman missiles found targets, wounded chariot horses went down, spewing out passengers. Surviving vehicles swung away and made way for the British infantry.

“At first, the legion kept its position,” Tacitus wrote of the 14th Gemina. [Tac.,

XIV

, 37] Then, Roman trumpets sounded “Charge.” With a roar, the men of the 14th “rushed out in a wedge formation,” and the two tight-knit wedges either side of them did the same. The two enemy forces crashed together. With shields pumping in and out and swords jabbing over the top, the Roman wedges were like machines. On the flanks, the Roman cavalry also became engaged, using their javelins as lances. [Ibid.]

Romans and Britons “contended for a long time,” said Dio, “both parties being animated by the same zeal and daring. But finally, late in the day, the Romans prevailed.” [Dio,

LXII

, 12] Britons, trying to retreat, created a crush that met the semicircle of their own wagons, which penned them in. Tens of thousands of Britons were trapped, and fell victim to legionary blades as the Roman force pressed all the way to the wagon line. The immense slaughter during this battle was to include British women

at the wagon line; it was estimated that 80,000 British warriors and civilians died. Even baggage animals perished in the maelstrom. Total Roman casualties were an estimated 400 dead, and a similar number wounded. [Tac.,

A

,

XIV

, 37]

Ironically, the most deadly battle ever to take place in Britain was never given a name; perhaps it might be called the Battle of Watling Street. Boudicca escaped from the battlefield, but within a few days she too was dead, taking poison, according to Tacitus. [Ibid.] “The Britons mourned her deeply,” said Dio. [Dio,

LXII

, 12] When camp-prefect Postumus of the 2nd Augusta Legion at Exeter came to hear of the battle and the signal Roman victory, he fell on his sword rather than face arrest for disobeying orders, which would have resulted in court martial and an inevitable death sentence.

The Palatium rushed reinforcements to Britain to make up for losses suffered during the revolt, among them eight cohorts of auxiliaries and 1,000 cavalry. Uniquely, 2,000 legionaries were also detached from a legion on the Rhine to fill the places of the men of the 9th Hispana lost under Cerialis. [Tac.,

A

,

XIV

, 38] Everything points to these legionaries being recent recruits to the 21st Rapax Legion at Vindonissa. Later events show that the Rapax was well under strength eight years later, missing at least four cohorts, indicating that it never received replacements for the men sent to the 9th Hispana.

Governor Paulinus, stung by the uprising and the destruction that had resulted, kept his troops in the field and “under canvas” right through the winter of

AD

60–61 as he strove to capture those rebels who had escaped, determined to damp out the last fires of rebellion across southern England. [Ibid.] Julius Classicanus, the official sent by the Palatium to replace the cowardly procurator Catus, reported to Rome that the troubles in Britain would continue while the vengeful Paulinus remained in charge. In late

AD

61, Paulinus was recalled to Rome, with Petronius Turpilianus replacing him as propraetor of Britain.

Despite the recall, Nero awarded the coveted Triumphal Decorations to Paulinus for his British victory, and six years later Paulinus was given a second consulship by the emperor. The 14th Gemina Legion was also recognized. Tacitus would later report: “The 14th having particularly distinguished itself by quelling the revolt in Britain, Nero had added to their reputation of by selecting them as his ‘most effective’ troops.” [Tac.,

H

,

II

, 11] There would never again be an uprising by British tribes in southern Britain.

AD

62–63

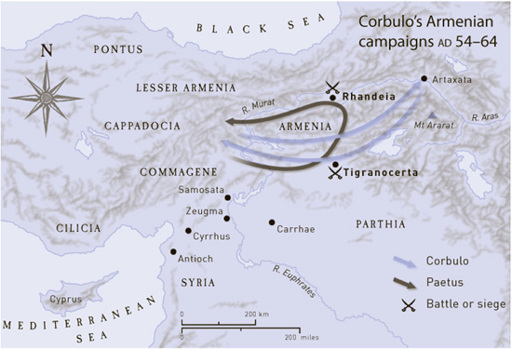

XXI. CORBULO’S SECOND ARMENIAN CAMPAIGN

Snatching victory from disaster’s door

In

AD

62, Armenia again erupted in conflict, as Parthia reasserted its claim to the country by invading it. The Parthian invasion force was led by Moneses, King Vologases of Parthia’s best general. The Parthians surrounded the new Armenian capital, Tigranocerta, where the king installed by Rome, Tigranes, was fiercely defended by his Roman bodyguard. When word of the invasion reached Corbulo in Syria, he sent two legions under Verulanus Severus marching up into Armenia at full speed to relieve the Roman defenders.

As the two legions approached, the Parthians suspended their siege and withdrew from Armenia. The Roman garrison also withdrew from Tigranocerta and joined the two legions in camp across the border in Cappadocia for the winter. Corbulo now sent to Rome for reinforcements and a senior general to take charge of the defense of Armenia. In response, the Palatium sent out the boastful Gaius Caesennius Paetus,

a consul in

AD

60, together with the 4th Scythica Legion from Macedonia and the 5th Macedonica Legion from Moesia, the latter having recently replenished its ranks with a new enlistment of recruits in Moesia. Paetus chose to leave the 5th Macedonica in Pontus after it landed from the fleet that had brought it across the Black Sea. Over-confident, Paetus felt sure he would only need two legions in Armenia, and summoned a legion from the Syrian station, the 12th Fulminata, to join the newly arrived 4th Scythica.

In the meantime, the Parthians had sent envoys to Rome, but, unable to reach an agreement with Nero, King Vologases recommenced hostilities, aiming now not only to occupy Armenia but to invade Syria as well. To defend Syria, Corbulo had the 6th Ferrata, 10th Fretensis and cohorts of the 3rd Gallica Legion dig in along the bank of the Euphrates river, Syria’s natural border with Parthia. Paetus, meanwhile, declaring that he would achieve total victory, crossed the Euphrates with the 4th Scythica and 12th Fulminata legions and entered Armenia. From the beginning, the omens were not good: the horse carrying Paetus’ personal consular emblems across the bridge spanning the Euphrates took fright and bolted to the rear.

The inept Paetus subsequently camped at Rhandeia in northwestern Armenia for the winter, even allowing a number of his men to take leave. From Rhandeia, Paetus wrote a letter to Nero “as if the war was finished, in pompous language, but barren of facts.” There at Rhandeia, the Parthian army surrounded the Roman camp and subjected it to a grueling siege. As the weeks passed, Paetus’ increasingly hungry and poorly led troops lost the will for offensive action. Now Paetus wrote to Corbulo, begging him to come rescue him. [Tac.,

A

,

XV

, 8]

Corbulo, after repulsing the Parthian attack at the Euphrates, methodically put together a relief column, including an ala, or wing, of camels carrying grain. Even as Corbulo was marching to Armenia, Paetus was agreeing to humiliating terms with the Parthians for a Roman withdrawal. After leaving all their baggage and piles of Roman dead at Rhandeia, and building a bridge for the Parthians, Paetus retreated from Armenia with his two shambling legions. When Paetus met Corbulo coming the other way, he was all for joining forces and marching back into Armenia, but the disciplined Corbulo replied that he had “no such instructions” from the emperor, and both Roman forces withdrew. Once news of this reverse reached Rome, “people were utterly disgusted with Paetus,” said Tacitus. Paetus was recalled to the capital, but Nero pardoned him “with a jest.” [Tac.,

A

,

XV

, 17; 25]

Corbulo, after bolstering his forces with the 5th Macedonica and 15th Apollinaris legions, conducted negotiations with the Parthian king Vologases from a position of strength. In the end, it was agreed that Corbulo would withdrew his troops from Parthian soil east of the Euphrates and the Parthians would withdraw from Armenia. Just as importantly, the peace treaty negotiated by Corbulo and Vologases stipulated that Vologases’ brother Tiridates would resume the throne of Armenia, but would become an ally of Rome and swear allegiance to Nero.

Within several years, as part of this treaty, Tiridates would go to Rome to bow down to Nero personally. Meanwhile, Corbulo, one of Rome’s best generals, would be forced to commit suicide after his son-in-law Vinianus Annius, who commanded the 5th Macedonica Legion in the last stages of the Armenian operations, foolishly implicated him in a plot against Nero.

AD

66

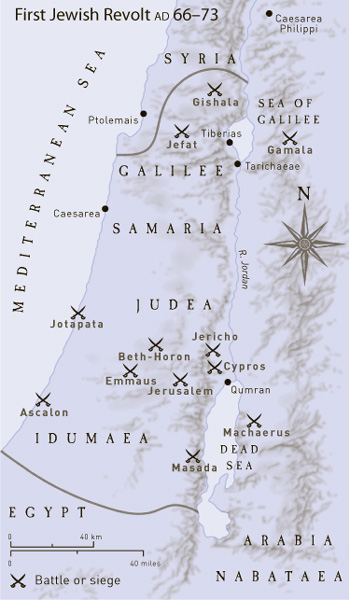

XXII. FIRST JEWISH REVOLT

Death in Judea

The coals of revolt had been glowing hot in Judea ever since Gessius Florus had been made procurator of the sub-province in

AD

64. Florus’ rapacity and brutality would soon fan the revolt into all-devouring flame.

On June 3,

AD

66, Florus arrived at Jerusalem from the provincial capital, Caesarea on the Mediterranean coast, with two legionary cohorts—almost certainly from the 3rd Gallica Legion—to punish the Jews for recent rioting. After allowing one cohort to loot the city precinct of Betheza, or New City, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Jews, a vast mob cut Florus off at the Antonia Fortress. By agreement with the Jews, Florus slipped out of Jerusalem in the dead of night, leaving just a single legionary cohort in the city.

Complaints from Jewish leaders about Florus’ heavy-handedness brought no response from his superior Cestius Gallus, propraetor of Syria, so they sent to King Agrippa of Chalcis, asking for help before things got out of hand and local resentment turned into rebellion. Agrippa, a pro-Roman Jew, sent 2,000 troopers from his bodyguard to Jerusalem to dampen the unrest. But by the time they arrived, Eleazar, captain of the Temple Guard, had taken possession of the lower city with thousands

of his men and was besieging the lone cohort of the 3rd Gallica stationed at the Antonia Fortress and Herod’s Palace. Other rebels were trying to break through the huge Temple doors. From throughout the city, Jews flocked to join the uprising.