Legions of Rome (91 page)

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

In July, with the main body of the Visigoths known to be encamped near Adrianople, Valens’ senior general Sebastianus was marching to Adrianople with the advance element of Valens’ army. He had detached 300 men from each of his legions and sent them ahead to destroy a large band of Visigoth looters spotted by his scouts. The legionaries achieved the objective, and recovered so much plunder from the butchered Visigoths that there was not enough room for it all inside Adrianople. The emperor Gratian, meanwhile, while hastening east with his troops to link up with Valens, was delayed in Pannonia when his column was attacked by Scythians of the Halani tribe.

According to the Roman writer Ammianus, who had been an officer of the Roman army under the three previous emperors, Valens was jealous of his nephew’s military success against the Alemanni, and even jealous of the initial success of his own general Sebastianus on the road to Adrianople. [Amm.,

XXXI

, 12, 1] He therefore set off with the bulk of his army, intending to demonstrate his prowess in controlling the Goths. As he approached Adrianople with his troops marching in square formation, his scouts reported that a slow-moving column of Gothic wagons had made its way through the hill passes to the north and was 15 miles (24 kilometers) from Adrianople. According to the scouts, there were 10,000 Gothic fighting men with the wagon train along with their family members.

On reaching Adrianople in the first week of August, Valens had his troops build a camp outside the town, with ditch and rampart topped by wooden stakes, in the old Roman manner. There at the Adrianople camp, while impatiently awaiting the arrival of Gratian and his army, Valens was joined by Richomeres, a count commanding Gratian’s household troops. Count Richomeres brought a letter from

Gratian in which the emperor of the west assured his uncle he would soon join him, and urged him not to venture anything before his arrival.

On a hot August day, a council of war took place in Valens’ pavilion at Adrianople, as Valens sought the opinions of his subordinates on what to do. Should he wait for Gratian, or should he attack the Goths at once? Sebastianus urged him not to wait, but launch an attack on the Goths immediately, a view supported by a number of others. But Victor, Valens’ Sarmatian-born Master of Cavalry, counseled his emperor to wait for the arrival of Gratian’s army from Gaul, and he was supported in that view by numerous other officers.

In reality Valens did not want to share a victory with his nephew. He wanted to attack at once. He chose to accept the advice of Sebastianus, perhaps reminding his courtiers that Constantine the Great had won a great victory near Adrianople in

AD

324, against his rival Licinius, to make himself emperor of the entire Roman Empire. That famous victory probably encouraged the hawks among Valens’ counselors to think that this would be the place where Valens should similarly gain great glory. Orders were therefore issued for the army to prepare for battle next day.

As preparations were under way, a Christian elder came as envoy from the Theruingi tribe’s Fritigern, king of the Visigoths, and presented Valens with a letter from Fritigern saying that if Valens would grant his people all of Thrace, together with its crops and flocks, he would guarantee a lasting peace between the Visigoths and Rome. Valens sent the envoy away.

At dawn on August 9, Valens’ army passed out of the gates of its camp outside Adrianople in battle order. According to some modern authorities, that army numbered 60,000 men. [Warry,

WCW

] With the cavalry taking the roads and the infantry marching over open country, “a suitable guard of legions” was left behind at the camp, which contained Valens’ imperial treasury, the emperor’s personal insignia, the individual packs of the soldiers and all the army’s baggage. [Amm.,

XXXI

, 12, 10] These legions would also be guarding the arms in the Adrianople arsenal, for Adrianople was one of thirty-four cities across the empire which then housed a state arms factory. [Gibb.,

DFRE

,

XVII

]

Valens had received a report from his scouts that the enemy had formed a vast circle of wagons on a hill some miles away. It was toward this hill encampment that the army marched all morning, over rough ground and in intense heat. At around two o’clock in the afternoon, the men of the Roman army could see the massive Gothic

wagon circle on the hill ahead, perfectly formed and looking like a wall of wood around the slope.

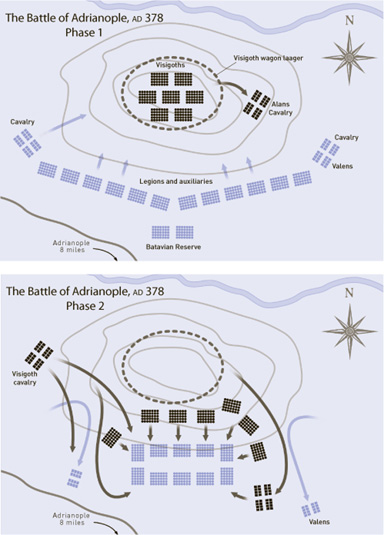

Although his men had been marching for something like eight hours, and were tired, thirsty and hungry, Valens ordered battle lines to be formed. Roman trumpets sounded the order, and the infantry spread into lines, taking positions allotted to them at that morning’s assembly. The leading elements of the Roman cavalry moved to occupy the right wing. Other troopers assigned to the left wing were still coming up country roads, so that the left was not yet properly filled out. In the center, the Roman infantry stood glaring across the parched expanse of earth separating them from the Visigoths who, summoned by their horn-blowers, were taking position at their wagons in their thousands. The Romans began to clash their javelins and lances rhythmically against their shields.

From the Visigoth encampment, King Fritigern again dispatched envoys seeking peace, but Valens sent them away, saying that a peace agreement could only be negotiated by men of rank. So Fritigern sent a message to say that the Romans should send several high-ranking Romans to his encampment to discuss peace terms. Valens did not know

that Fritigern was playing for time. The Visigoth cavalry, led by the kings Saphrax and Alathe of the Greuthingi tribe, was absent from the camp, apparently only gathering fodder in the vicinity, and as soon as the Roman army had been spotted approaching, Fritigern sent messengers galloping to find them and bring them to the aid of their people. The Roman leaders discussed who should go as envoy to Fritigern, and Richomeres, the count from Gratian’s household command, volunteered to go to the Goths’ camp.

As Richomeres was about to ride up to the massive circle of wagons on the hill, some of Valens’ mounted troops, apparently stationed on the Roman left, lost patience and commenced an attack of their own accord, urged on by their over-confident officers. These men, Armenian horse archers of the Comites Sagiittarii Armeni led by the tribune Bacurius of Hiberia, from northern Armenia, and cavalrymen of a Scutarii squadron led by a tribune named Cassio, charged up to the wagon line and engaged the Visigoths. But they were met by such a hail of arrows and other missiles that they turned tail and galloped back the way they had come before many minutes had passed, which did nothing for the confidence of the remainder of the Roman army.

Now, the Goth cavalry under Saphrax and Alathe arrived, accompanied by Halani allies, and thundered into the rear of the Roman army. Valens had not put out cavalry patrols to warn him of the approach of enemy reinforcements—which meant that he and his army were taken completely by surprise as the Goth cavalry charged into his stationary army and mowed down Roman soldiers in their path. The charge broke up the Roman lines and a number of battles followed.

Roman infantry and some cavalry were locked in combat with the Goth cavalry. On the left, the Roman infantry advanced of its own accord all the way to the wagon line. But the Roman cavalry on the left had been so disorganized by the rash charge by the horsemen of Bacurius and Cassio that the infantry lacked cavalry support. They were met by a wave of Goths that came out of the wagon line like water from a breaking dam and washed over the Roman left. The Roman infantry here was so crushed together that “hardly anyone could draw his sword or pull back his arm.” [Ibid., 13, 1] The fighting raised a dust cloud which cut visibility dramatically. This prevented Roman infantry from spotting Gothic arrows that came in clouds from the wagon line, killing or wounding them in their thousands.

Describing the battle, Ammianus spoke of Romans and Goths wielding the battleaxes that had become common weapons for infantrymen: “On both sides, the strokes of axes split helmet and breastplate.” He described Goths who’d had their hamstrings

severed or right hands lopped off in the fighting yet who still fought with defiant courage. One Goth, he said, though pierced through the side and near death, was still “threateningly casting about his fierce glance.” Romans, their lances broken, and seeing no way of escape, weighed into the enemy with their swords, determined not to sell their lives cheaply. [Ibid., 13, 4]

The Roman lines had been completely broken by the rush of Goths from the hill. The number of 10,000 that Valens’ scouts put on the Gothic warriors proved woefully short of the truth. Modern-day authorities suggest that there were 200,000 Goths present that day—men, women and children—and that as many as 50,000 of them were warriors who took part in the battle. [Warry,

WCW

] Not only did they almost match the Romans in numbers, the Goths had in their favor the element of surprise with the unexpected arrival of their cavalry, plus the impetus of their infantry charge from the wagon line on higher ground.

All over the body-strewn field, Roman units broke and their men ran. Valens, never one to inspire devoted loyalty from his troops, was even deserted by most of his imperial bodyguard. In the middle of the Roman line, two Roman legions had unflinchingly held their ground. One was a Mattiarii legion, either the Mattiarii Seniors or the Mattiarii Juniors, which were Palatine legions. The other was a Palatine legion made up of foot lancers—either the Lanciarii Seniors or Lanciarii Juniors. All the Palatine legions were considered elite units, and were paid more and received more imperial favors than other units. Valens took refuge with these two steadfast but encircled legions, as they fought off each barbarian attack.

Seeing the emperor with these two legions, old Count Trajanus, the former commander-in-chief of Valens’ troops who had been recalled from retirement by Valens for this campaign, yelled out from the back of his horse that, as Valens had been abandoned by his bodyguard troops, all hope was gone unless he called up the foreign auxiliaries that he had placed in reserve.

Valens agreed, and above the din of battle Trajanus instructed the Sarmatian Victor, his Master of Cavalry, to ride with all speed to summon up the famously tough Batavian auxiliaries who had been held in reserve—the Batavi Seniors and/or the Batavi Juniors—and the Palatine auxiliary units. Bent on his mission, Victor turned his horse around and slashed his way through the surrounding Visigoths, but when he reached the place where the Batavian troops should have been, there was no sign of them. They too had fled. So Victor kept riding. [Ibid.]

The fighting, which had raged all afternoon, continued into the twilight. And then night fell; an inky, moonless night. With its arrival, the battle ended. The Roman army had been destroyed. Ammianus estimated that no more than one third of the troops in Valens’ army escaped with their lives. Modern authorities put the Roman losses at 40,000. [Warry,

WCW

] Certainly Roman casualties were massive. Ammianus said that the roads were blocked with the dead and the dying. “With them also mounds of fallen horses filled the plains with corpses.” [Amm.,

XXXI

, 13, 11]

Valens’ most senior generals, the counts Sebastianus and Trajanus—one who encouraged the early battle, the other who had stayed with his emperor to the last—both fell on the battlefield. Thirty-five Roman tribunes also perished in this bloody defeat that became known as the Battle of Adrianople. One of the Roman officers to fall that day was Potentius, a tribune “in the first flower of his youth” who had commanded a Palatine mounted unit, the Equites Promoti Seniors, which was apparently made up of men promoted from other units. Potentius would have been a personal friend of the historian Ammianus, for he was the son of Ammianus’ former chief, Count Ursicinus, who had been Roman commander-in-chief under the emperor Constantius

II

. [Ibid.,

XXXI

, 13, 18]

As for the emperor Valens, he was never seen again, dead or alive. Ammianus related a story told by a young officer cadet of the Candidati Militares relating his fate. The soldier said that Valens, though wounded by an arrow, had escaped from the battlefield late in the day with a few officer cadets, including the teller of the tale, and some eunuchs from the Palatium staff, and found refuge in a two-story farmer’s cottage nearby. While Valens’ companions were attempting to treat his wound, the cottage was surrounded by Gothic warriors. As the Goths were attempting the break down the bolted doors, one or more of the officer cadets from Valens’ party loosed off arrows at the attackers from an upper window and drove them back. The Goths then piled firewood against the house, and set it alight.

As the cottage burned, the storyteller decided to take his chances with the Goths, and dived through a window. None of the other occupants of the cottage emerged from the flames, and all perished. The young officer cadet was made a prisoner by the Goths, who were appalled when they learned from him that they had just fried the Roman emperor, for they would have won great glory among their people had they captured Valens alive. The young officer cadet later escaped from his captors, found his way to Roman forces and told his story. [Ibid.,

XXXI

, 13, 14–16]