LEGO (3 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

But this problem can be solved, too. I’ll seek out talented builders, at conventions and online, to discover what it takes to master building techniques. And I choose to believe that my abilities haven’t regressed with age. I played with LEGO bricks once, and what I made was good. LEGO doesn’t change—the bricks today are the same as when I was ten—but I’ve changed, and the adult me is better equipped. I’m smarter and physically stronger. I can do this.

As I anticipate learning to build again, I feel excited that I’ll see the extremes of adult builders, including the Toy and Plastic Brick Museum, one fan’s multimillion brick collection of LEGO sculptures and artifacts set inside a former middle school. I’m compelled to learn how a tiny LEGO man is transformed into a tiny LEGO Iron Man and how the

Mona Lisa

is recreated in a brick mosaic.

Mona Lisa

is recreated in a brick mosaic.

And in the center of everything sits the LEGO Group—a toymaker that in recent years has tried to figure out how to court a small but vocal adult audience. It is not lost on me that their U.S. corporate headquarters are in Enfield, Connecticut—my home state—so I’ll be making a mandatory stop to build again with my dad. Not to mention that I’ll be going to Denmark in an effort to understand the culture of LEGO, and taking Kate with me.

I’ve got a year to build, and anything is possible.

2

I Need a Playroom

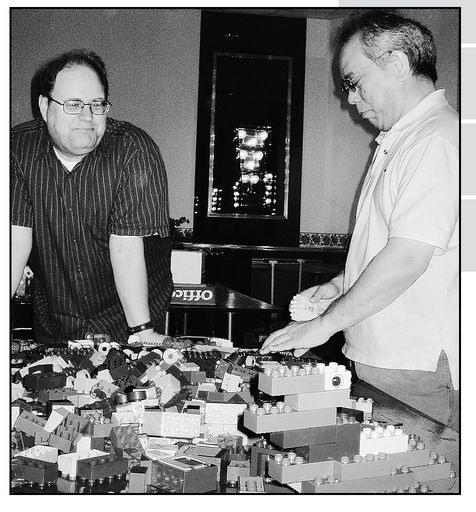

AFOLs Duane Collicott (left) and Joe Meno play with DUPLO bricks the day before Brick Bash 2008 in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Before I can build with LEGO again, I have another milestone to contend with—turning thirty. It’s my birthday, March 22, and I’m on my third cupcake—one for each decade. I feel a little sick, but happy. Guilt doesn’t come until the doorbell rings and my in-laws arrive with a suitcase-size box to find me on the couch with frosting on my sleeve and wrappers stacked neatly on a plate.

I offer them cupcakes, and they sensibly share one between them as they wait expectantly for me to open my gift. I tear open the green wrapping paper and sit back admiring the LEGO set I have asked for on this, my thirtieth birthday. I haven’t been this excited since I was in the fourth grade and my parents told me I could have my birthday party at a bowling alley.

“Do you like it?” asks Ann, my mother-in-law.

“The Trade Federation MTT This is awesome,” I gush.

An oversize brown ship that holds sixteen Star Wars droids dominates the 1,362-piece set—the floating ship was the attack vehicle used by the droid army in

The Phantom Menace.

It’s the first major set I’ve ever owned with a retail price of $99.99. It’s the kind of present I didn’t know I wanted until I saw it.

The Phantom Menace.

It’s the first major set I’ve ever owned with a retail price of $99.99. It’s the kind of present I didn’t know I wanted until I saw it.

“I didn’t know that they made sets that big,” says my father-in-law, Bob.

I flip the box over on the ottoman, trying to keep the conversation going as I stare at the various pieces and minifigures included in the set. It’s funny because while my in-laws are there, I can only focus on getting started with building. But once I’m by myself, I’m unsure how to start, and instead I make a big production of washing and putting away the dessert plates.

After they leave, I realize I’m intimidated by the size of the LEGO set in front of me. I carry the box upstairs to our spare bedroom and lean it against the wall.

It is the room most often skipped when we give guests the tour of our house. My wife and I have been trying to conceive for a few months, and someday this will be our child’s room. But for now, wrinkled clothing sits forgotten on the ironing board, and both of us try not to spend much time in the empty space. I’m not sure if I’m leaving the set here because it is a room of uncertainty, or if I’m hoping it will serve as some sort of good luck totem.

If you set out toys, then babies will come.

As if children were just available in the wild, ready to be ensnared by my commerce-inspired trap. At the end of the day, I put the set in that room for one simple reason—it is where I put things that I don’t want to think about.

If you set out toys, then babies will come.

As if children were just available in the wild, ready to be ensnared by my commerce-inspired trap. At the end of the day, I put the set in that room for one simple reason—it is where I put things that I don’t want to think about.

It works. Nearly a week passes before I think about the set again. And by that time, I’m 750 miles away in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to meet Duane Collicott, who is hosting the first LEGO convention of the calendar year.

Six days after my thirtieth birthday, I’m pacing inside the entryway of the Four Points Sheraton, nervous about meeting an AFOL—an adult fan of LEGO. I wish that I had built the MTT Federation so I could have at least one accomplishment to casually mention. But instead, all I can do is pace. The sliding door has a motion sensor that I set off repeatedly. I look back guiltily at the front desk manager, who is not smiling. I take a seat in the wingback chair by the entryway.

A white minivan pulls up, piloted by Duane, forty-four, a computer software programmer wearing jeans and a red-striped shirt, and a pair of squared-off glasses. Reddish-brown hair sprouts in tufts around his bald crown. He jokingly refers to himself as the “number-one geek” in Ann Arbor, after a local news reporter recently found him online by doing a Google search for the word “geek.” Duane has an offbeat sense of humor and the propensity to announce what he is going to do right before he does it.

“I’ll just wait at this light here because we’re never going to be able to make the turn,” he tells me before we pull in for breakfast at the Coney, an Ann Arbor staple that is half diner, half hot dog stand. Over eggs and coffee, he tells me about Brick Bash, the LEGO convention he organized for the first time in 2005.

“There are two types of AFOLs. Those that want the public exposure and the chance to show off what they have built, and those that just want to have a hobbyist convention,” says Duane.

“Which one are you?” I ask.

“Well, the public is invited to Brick Bash. Which one do you think?”

Duane came home burning with the idea after attending his first LEGO fan convention—the now defunct Chicago House of Bricks—in May 2005. It was there that he unveiled his first large sculpture, a thirteen-foot to-scale re-creation of the Maumee River Crossing Bridge (now known as the Veteran’s Glass City Highway) in Toledo, Ohio.

“I started out with one table and then I just took over another,” says Duane, describing how he laid out the 260 white segments that frame the main expanse of the bridge, which in real life has a span of 1,220 feet. The bridge model features LEGO rope for the cable suspensions and translucent bricks along the central column. A commitment to using only LEGO parts is important to many adult fans, those I would come to know as “purists.”

Purists don’t cut or paint bricks. They don’t make their own stickers to add details. If LEGO doesn’t make it, they’re not using it. And with those limitations comes a perverse pride in figuring out how to creatively use what is available.

In Chicago, Duane discovered the world of purists, who shared tips on building and wanted to know about what he had built. He was also fascinated by the science fiction convention that shared event space with the LEGO enthusiasts. “I came across a woman dressed as a pirate wench by the vending machine. I was glad I didn’t bring my son.”

He returned to Ann Arbor determined to organize a gathering that year for local LEGO fans. The first Brick Bash attracted just over three hundred people. He’s organized the convention for the past four years because he loves the feeling of a few hundred people crammed into a poorly air-conditioned room sharing their love for a little plastic brick. It’s not always fun to build alone.

“I remember a time when my dad and I are hanging out. We’re the last ones there at Boy Scout camp. I hate the feeling. It’s like old newspapers—they have no purpose. I don’t like being the only one left at a place after it’s over,” says Duane.

After breakfast, the work begins. We head about two miles west of the University of Michigan campus before Duane pulls his minivan up in front of the Courthouse Square Apartments in downtown Ann Arbor. He briefly wonders out loud if a pick-up truck is going to pull away from the curb before we come to a stop.

Opening the rear door, Duane asks me to help him move the nine translucent tubs filled with LEGO pieces. I reach for a storage tub and briefly stagger under its weight. It will take several trips to unload the van.

“This is heavy,” I tell Duane as the first beads of sweat roll down my neck. He just grins. We stack six tubs on a hand truck, which Duane wheels over a black mat with a floral print outside the building. The mat says, “Welcome home.”

The Courthouse Square Apartments is an affordable housing community for seniors over fifty-five. We enter the foyer, and the hand truck wheels sluggishly move across the deep red carpet. A receptionist stands up and slides back the glass partition separating her office from the hall.

“You gonna do something with all those little pieces?” she asks, eyeing the tubs skeptically.

Duane nods and stops long enough to invite her to the event. In the elevator, he explains that Brick Bash has outgrown its previous two spaces. The library was too small. The university was too expensive. The ballroom on the second floor of the Courthouse Square Apartments was priced right at $750 and was available.

The minivan unloaded, we leave for the airport to pick up Joe Meno, a fellow AFOL who is flying in from Raleigh, North Carolina. A short Asian man with glasses walks out of the sliding doors at Detroit Metropolitan Airport. A cell phone is clipped to his belt via a red case that resembles a LEGO brick. His white polo shirt matches his classic white sneakers. A graduate of the North Carolina State School of Design, he has dreamed of designing sets for science fiction movies and even had a six-week stint as an employee at a LEGO retail store. If Duane is a PC, Joe is a Mac.

This is the editor of

BrickJournal,

the magazine for adult fans of LEGO. One of his suitcases is full of the glossy magazines, which he intends to sell at the convention. I will buy one for $7, a discount off the $8.95 newsstand price.

BrickJournal,

the magazine for adult fans of LEGO. One of his suitcases is full of the glossy magazines, which he intends to sell at the convention. I will buy one for $7, a discount off the $8.95 newsstand price.

Duane tells me right before Joe comes out of the airport that they’ve only seen each other in person a handful of times. I had wondered if adult fans would have difficulty interacting face-to-face, when so much of the community is dependent on online interaction. But they fall into an easy conversation on the ride back to the Courthouse Square Apartments.

The tubs we brought up earlier to the ballroom need to be unpacked; Duane turns over the first tub, and DUPLO bricks—LEGO elements intended for the toddler set—crash onto a six-foot wooden fold-out table in a primary-colored splash of noise.

“Imposter!” Duane shouts as he pulls a MEGA Bloks brick out of the pile. The popular plastic toys are manufactured by MEGA Brands, Incorporated, the main competitor to LEGO, based in Montreal, Canada. He keeps snatching up pieces and tossing them to the floor.

“How do you know?” I ask, fiddling with an oversize green brick.

“You can feel the difference, and when you drop it, it makes a different sound,” says Duane as he drops a MEGA Blok and DUPLO piece in quick succession. I’m reminded of wind resistance experiments.

“MEGA Bloks sound hollow,” says Joe.

The mixing of MEGA Bloks and LEGO is one of the major pet peeves of adult fans of LEGO. It’s a common problem when you’re buying at a garage sale or on eBay. The average person doesn’t differentiate between the products because they technically can stack together and are interchangeable. But to an AFOL, it’s like mixing premium goods with a generic store label, devaluing the rigorous quality control standards of the LEGO Group.

Duane continues to root out the offending blocks, while Joe and I unconsciously begin to snap together DUPLO bricks.

I stack together six bricks in rapid succession, excited to have built what I believe resembles an alligator. I hold it up to Joe and Duane.

“Very nice,” says Joe, in the manner of a parent who is unsure what his child has built but wants to encourage him to keep building. Joe holds up what he has been working on for the past few minutes. It’s a Tyrannosaurus Rex, made from the oversize child bricks.

“Wow,” I exclaim, “that’s awesome.” I suddenly have the vocabulary and hero worship complex of a twelve-year-old.

Joe and Duane begin opening other translucent tubs, all of which are filled with various LEGO products. I continue to stack together DUPLO bricks in the hopes of building something that will impress the two men I have just met.

I am fully aware that I am building poorly with a product that was once known as LEGO Preschool. DUPLO bricks are twice the height, length, and width of a traditional LEGO brick. This makes them easier for small children to hold, and reduces the possibility that they’ll swallow one. I guess I can consider it a small victory that thus far I can hold them and have managed not to choke myself. DUPLO appeared in 1969 with the recognizable configuration of two rows of four studs each—the classic LEGO standard of a 2 × 4. In true modular fashion, LEGO bricks can be stacked on DUPLO bricks.

“Bionicles,” says Duane from across the room as a white top burps open. “I got them cheap because nobody else wants them.” He is sitting cross-legged on the ballroom’s thick carpet.

Other books

The Firebird Mystery by Darrell Pitt

Liberty Silk by Beaufoy, Kate

Darkness Bound by Stella Cameron

His To Own by Black, Elena

Alone Beneath The Heaven by Bradshaw, Rita

The Fall of Never by Ronald Malfi

Marjorie Farrell by Autumn Rose

Believing in Dreamland by Dragon, Cheryl

The Unplowed Sky by Jeanne Williams

Love Letters From a Duke by Elizabeth Boyle