Leon Uris (22 page)

Authors: The Haj

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #History, #Literary, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Middle East

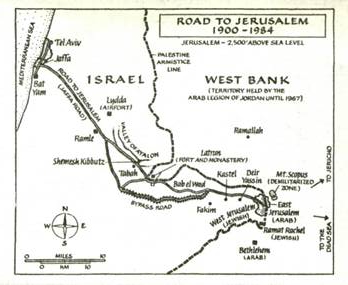

At that instant the headlight of a car fell on the sign that read

SHEMESH KIBBUTZ

. I was drawn toward it, mesmerized. I knew I was forbidden to enter, but if I begged the Jews not to tell my father, perhaps they could find an Arab doctor for me. Then spotlights blazed through the rain from the guard post of the kibbutz, once again blinding me. I was suddenly surrounded by a number of Jews holding rifles on me. They took me inside the gates.

‘What is he saying, Avi?’

‘Something about a sick baby.’

‘Does anyone know him?’

‘Isn’t he one of the muktar’s children from Tabah?’

‘Someone get Gideon.’

‘What’s going on over there!’

‘It’s a child from Tabah. He keeps repeating that a baby is very sick.’

I must have fainted. The next I remember was being in the seat of a truck with Mr. Gideon Asch holding his arm around me and another man driving, trying to get up the muddy street to the center of the village. The truck spun and slid all over the place.

‘They live up there!’

‘The road is impassable. We’ll have to walk.’

I fell down into the mud and was unable to get up. Mr. Gideon Asch swept me up in his good arm and the three of us, running, slipping, and falling, made our way up the path to my father’s house. The two Jews pushed through a number of people who had gathered outside in the rain.

Mr. Gideon Asch and the other man were standing inside the living room. I was set down and I swooned into Nada’s arms but managed to remain conscious. Mr. Gideon Asch explained that the man with him was a physician.

Haj Ibrahim stood across the room, blocking the doorway to Ramiza’s room. After a strange silence Hagar and Nada and my father and the daya all started yelling at once.

‘Calm down everyone!’ Mr. Gideon Asch bellowed over everybody’s voice.

‘Where is the baby?’ the doctor asked.

Haj Ibrahim took a couple of menacing steps toward me and raised his fist. ‘I told you! I told you to go to Latrun!’

‘Father! We could not get a doctor from Ramle or Lydda!’ I cried in defense. ‘I did not know what to do.’

‘Please let me see the baby,’ the doctor pleaded.

‘No!’ my father roared. ‘No! No! No!’ He pointed menacingly at me. ‘You bring them here to show them how inferior we are!’

‘Ibrahim,’ Mr. Gideon Asch pleaded, ‘I beg you to calm down. Stop talking like a fool. There is a child’s life at stake.’

The women began wailing convulsively.

‘No pity from the Jews! No pity! No mercy! I will not have you coming into my home to prove your superiority!’

Mr. Gideon Asch made a move toward the bedroom, but my father blocked the way. ‘Don’t do this, Ibrahim! I implore you! Ibrahim!’ My father did not budge. ‘You are committing a grave sin.’

‘Hah! The sin is to receive mercy from a Jew! That is the sin!’

Mr. Gideon Asch threw up his arms in defeat and shook his head at the doctor. My father and the women howled louder, he to make them go and they to keep the doctor there.

An unreal silence suddenly descended. Ramiza, chalky-faced, ghostlike, mouth gaping in a trance, walked in with the baby in her arms. The doctor pushed my father aside and took the baby as Ramiza crumpled to the floor and the women fell around her. The doctor held his head against the baby’s chest, slapped it, then breathed into its mouth, opened his medical bag, and listened again.

‘The child is dead,’ the doctor whispered.

‘This place is filled with evil spirits,’ my father said. ‘It is Allah’s will that the baby die.’

‘Allah’s will my ass!’ Gideon Asch gnarled. ‘That child died of filth and neglect! Come on Shimon, let’s get out of here.’

They plunged from the house into the awful downpour, with Haj Ibrahim roaring after them and shaking his fist. I did not hear any of the rest of it, but others did.

The two Jews slid and struggled for balance down the path of rocks, glazed by the rain, with the muktar behind them. ‘How we live is how we live! We have survived here for thousands of years without you! Our existence is as fragile as the mountain tundra! Why is it that you must always come in from the outside and tell us how to live! We don’t want you! We don’t need you! Jew!’

Gideon slammed the door on the driver’s side and groped for the ignition. The doctor jumped into the opposite seat as Haj Ibrahim pounded on the door and continued to shout.

Gideon closed his eyes, fought back tears, and for an instant dropped his head against the steering wheel. ‘Jesus Christ,’ he muttered. ‘I left my artificial hand at home. I can’t drive this damned thing.’

Before the doctor could get to the wheel, Gideon had flung the door open and walked down toward the highway.

‘Go fuck a dead camel!’ Haj Ibrahim screamed, ‘fuck a dead camel!’

END OF PART ONE

The Scattering

1946

I

T WAS A DAY OF

great sadness for me when I left school, but the decision was mine. I had turned ten years of age and knew more than anyone in the classroom, including Mr. Salmi. At first Mr. Salmi used me to read surahs from the Koran while he sat in the back of the class and napped. Then he put more and more responsibility on me to teach. I wanted to learn. I had taught the Jewish children in Shemesh Kibbutz, but I learned more from them than I taught.

The real reason I chose to leave school was because I was creating a place for myself at my father’s side. This gave me the courage to finally cross out of the world of women and the safety of the kitchen into the fearsome world of men. My mother’s plotting was behind the move.

From the moment the great Second World War ended, things went very badly in Palestine. As the respected Muktar of Tabah, my father had to ponder all the time. The news over the radio and in the Arab newspapers became violently anti-Jewish. My father said many times to me that our people were more easily moved by words than by ideas and more moved by ideas than by logic. He had depended upon Mr. Gideon Asch to explain the Jewish side of things. Since the night Ramiza’s baby died Mr. Gideon Asch never returned to Tabah, so my father was left with one point of view.

Each night there was a ritual in our house. Kamal read the Arab newspapers to my father. Haj Ibrahim would sit in his personal great chair while Kamal sat on the long bench, which was for the rest of the family and unimportant guests. Kamal was a poor reader and when my father got impatient it made matters worse. Kamal would stutter when he didn’t know a certain word.

‘You’re so dumb you couldn’t find your ass with both hands at high noon,’ my father often roared.

But Kamal would rather eat a mile of donkey turds than ask me about pronouncing a word. Hagar observed all this.

‘You will read for your father very soon,’ she promised. She went into a seduction of Haj Ibrahim and sure enough, after a few nights, he asked me to replace Kamal in reading to him. It was the most important day of my life up until then.

It was not difficult for Hagar to get my father into her bedroom and away from Ramiza. Ramiza was frightened all the time. She bit her lips and fingernails and slinked about like a cowering dog when my father was near. She listened keenly in case he issued an order, when she would jump to bring him his pipe or whatever he asked for and grin like an idiot when she handed it to him, hoping to get a nod of approval. She worked furiously at her chores, to avoid being yelled at, and virtually clung to my mother and Nada. At the slightest sign of friction she’d run off and weep. Ramiza became too timid to go to the village well or mingle with the women by herself.

We kept her as one keeps a feeble-minded sister. Hagar ceased being jealous and at times showed her kindness. My father did keep going to Ramiza’s bedroom, but there was gossip that he only wanted to look at her naked and make her dance for him. Once I overheard Hagar tell her to pretend to enjoy sex; she instructed her on certain kinds of movements to make with her body and on how to groan as if she were in ecstasy.

Kamal was absolutely furious at me for taking his place as the reader. His method of getting revenge was to marry in the hope of having a son so he could establish himself with a line of heirs. He married a Tabah girl, the daughter of a clan sheik. Her name was Fatima and she was homely. However, she had a pleasant way about her and she was plump, which many Arab men like very much. Haj Ibrahim was able to get her at a good price. The wedding was nowhere as grandiose as my father’s marriage to Ramiza had been, but Kamal was no treasure either, so they suited each other. Fatima became pregnant immediately, but fortunately for me and my mother’s ambitions, the baby was a girl.

Fatima was one of those bossy women one rarely sees. When Kamal ordered her around she obeyed, but she always got even with him. It appeared that Kamal was actually afraid of her. This was a joke because it only made Kamal look weaker in my father’s eyes.

Now that I was out of school I could spend my time studying the village books and records. This put Kamal at my mercy. I kept pretending to find new parcels of land on which no rents were paid. I say I pretended to find them because I had known about them all along. I had a secret pact with Kamal to share the rents on these parcels. Kamal remained too frightened to reveal our agreement to Haj Ibrahim. This left the way clear for me to ‘stumble’ on a new parcel when Hagar or I wanted something from him. Maybe Haj Ibrahim knew all along that I was cheating him because he certainly made enough remarks about Farouk and Kamal playing loose with the books. In all sincerity I did not feel too badly about it because I gave the money to my mother.

One night, just after the war ended, Radio Damascus broadcast news that death camps had been discovered in Germany and Poland. Many millions of Jews had been gassed to death by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. In the following days all the newspapers were filled with the revelation and every night on the radio it seemed another new death camp was discovered. Radio Cairo said that Churchill, Roosevelt, and the holy Pope in Rome had already known about the death camps during the war but kept quiet about it and let the Nazis kill the Jews without protest.

It was strange and shocking news for us. We had been living side by side with Shemesh Kibbutz for over two decades with no serious trouble and only ordinary hatred of the Jews. The death camp news brought an odd reaction from the villagers. It was as though their true emotions about Jews had been locked deep inside a cave with the entrance blocked. The rock had been blasted away and thousands of bloodthirsty bats poured out. I did not even know my people from the joyful way they were reacting.

I was still going to school at the time and in Ramle there were street celebrations over the death camps led by members of the Moslem Brotherhood. Mr. Salmi read surah after surah from the Koran to prove to us that the death camps were the fulfillment of Mohammed’s prophecy of the Day of the Burning for the Jews. It was all in the Koran, Mr. Salmi reasoned, so Mohammed obviously had a magical vision from Allah, and it proved the major point of Islam: what would happen to nonbelievers.

Uncle Farouk usually preached very dull sermons on the Sabbath, sermons about the great benefits that would come to the believers in death, or about giving money to the poor, or instructions on daily life. After the death camp news he began preaching from some of the most frightening surahs and verses: those dealing with the destruction of the Jews. My father, who always approved my uncle’s sermons in advance, sensed the new attitudes of the villagers, for he allowed the sermons to continue, Sabbath after Sabbath. The easygoing relationship with Shemesh was suddenly filled with suspicion and a tension I had never felt before.

Although the Arab press had jubilantly reported the genocide, they now did a complete turnaround. For months the newspapers had printed photographs of the gas chambers and ovens on the front pages. Overnight they said that the genocide never really took place, that it was all a trick of the Zionists to win the sympathy of the victorious Allies. Now the Allies would let all the Jews in Europe come to Palestine.

This was my first experience of seeing my people believe one thing one day and believe exactly the opposite the next. As quickly as the people in Tabah had accepted and had been elated over the burning of the Jews, they accepted that it had been a Zionist plot all along.

Haj Ibrahim was not certain. He did not get caught up in the instant emotionalism as the others did, but wanted to think it out. It was difficult for him, for he did not have Mr. Gideon Asch to speak with. Whatever did take place in Europe must have been very bad, for there was a rage brewing all over Palestine, a rage more fierce than during the Mufti’s revolt.

Jews began forcing their way into Palestine from Europe because they claimed they had no other place to go. If there had been a genocide, these people would have to have been the survivors. If the genocide was a Zionist lie, then these Jews were deliberately being sent into Palestine to displace us.

Haj Ibrahim had many failings, but he did not bite at words. He was the only man I knew in Tabah to question the radio or the newspaper or even the clergy, and try to find logic and truth. So my father mumbled aloud and posed questions to himself while I read to him.