Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill (5 page)

Read Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill Online

Authors: Diana Athill

The contents of an egg which was too far gone echoed other horrors: there was sometimes, for instance, a dead animal hidden in long grass. The gamekeeper’s ‘larders’ in the woods – wire strung with the rotting corpses of weasels, stoats, rats, jays, carrion crows and other threats to his pheasants and partridges – these were bad enough, but I knew where they were and could avoid them, or if I had to pass one because I was with someone who might think me silly, I could steel myself in advance, and look away. But sliding into a ditch to get at a clump of primroses: then, if there was suddenly a dead animal, my very blood recoiled. The worst was last summer, wading through a field of wheat (though trying not to trample it down, which was forbidden) for the pleasure of being in all that gold and smelling its warmth. My foot came down on a dead rabbit. Swerving, I almost landed on another, and realized that all round among the wheatstalks, partly hidden by the undergrowth of weeds, were collapsed skeletons with their loathsome tatters of fur – a sort of rabbit graveyard: how to escape without treading on another? Then panic sent me plunging out of the wheat. I could remember it only in quickly blinked-away glimpses, it was so dreadful. It did not stop me walking again through tall growth, or climbing into ditches, or exploring woods, but I was much more careful which diminished the pleasure.

It was a puzzle, the way things were rarely exactly what they ought to be. If I had run myself into a sweat, and the grass was so soft and green that it should have been caressing when I flopped down in it, there was usually a thistle or a hidden stone, or after a few seconds my legs would start to itch because of ants crawling over them. And if music started to climb higher and higher, instead of going up into absolute height it always turned and came down again. Height, depth, softness, sweetness – there was never quite enough of them. ‘Why can’t all food be sweet?’ I had asked not long ago, and the answer was ‘You couldn’t have sweet if you didn’t have sour’. What a senseless rule!

It wasn’t like that in the serial story I told Andrew every evening, when we were in bed. The story was called ‘Hal’s Adventures’. ‘Why Hal?’ my mother asked – we knew no one of that name – and I explained that it was short for ‘Halbert’. ‘But there’s no such name. There’s Albert or there’s Henry – Hal is short for Henry.’ I could not accept that because the abbreviation of Henry must so obviously be Hen; so Hal went on being short for Halbert, my hero who could command magic at a pinch and was absolute ruler of his people.

Hal’s closest friend and lieutenant was Thomas, who was trusty and also dull: all I bothered to know about him was that he had brown hair (Hal’s was auburn) and blue eyes. Thomas had a pretty princess with curly golden hair, but Hal’s princess was dark and tragic-looking, with hair that fell to her knees in smooth waves. If I could have had my way the story would have consisted almost entirely of what the princesses were wearing, what kind of horses they were all riding, what jewels adorned their chariots and thrones, what silks were heaped on their beds. Everything in their palaces was what it should be – all the food as delicious as strawberries and peaches, all the colours luminous. Once Hal and his entourage discovered a river of perfect beauty. Its water was as clear as diamonds and it ran over a broad smooth bed of spring-green grass.

My brother wanted events, not descriptions. I was bad at these, although I knew that marvellous things must happen in Hal’s world if only I could hit on them. Since I couldn’t, it always ended by being another battle between Hal’s forces and the Pubbies.

We had set out to invent a whole secret language, but it had stopped at a special grunt for ‘goodnight’, ‘jolyon’ for ‘penis’, ‘jellybolees’ for ‘buttocks’ and ‘pubby’. I felt ashamed of our lack of seriousness when we gave up. A pubby person was a person we despised: fat, soft, silly, scared. The Pubbies in the story were an obscene and treacherous army, always defeated, and tortured when taken prisoner. Once Hal and Thomas made them sit naked astride a wall with jagged glass on top of it, and bounce up and down – a stroke of genius which went down so well with Andrew that it often had to be repeated.

The worst thing we ever did to a pubby in real life was to push him into a bed of nettles as though by accident. Usually we went no further than acting aloof and showing off. The pubby would be handed over by its parents and our own – ‘Why don’t you take Michael to see the calves?’– and after a greeting which adults would think no worse than shy, we would start running along the tops of walls, jumping up to catch a branch over which to somersault, throwing stones at things (risky, because to miss made you look silly). If after a while the pubby joined in and proved as able as we were, he would be promoted – often with enthusiasm – to friend. If he was nervous, or didn’t like to get dirty, or was simply not interested, he was condemned.

I would never forget the day when I stood by myself on the bridge because it had so much in it: it was summer; it was in this place – our grandparents’ home – which all of us children felt in our bones to be our own; and it was near water. And perhaps also because I was alone, although I wasn’t really. Andrew and two of our cousins were quite near, climbing trees. I was separate because I was sulking. Their enthusiasm for tree-climbing had outweighed mine for something else, and ‘She’s sulking, she’s sulking,’ they had jeered. The way to lift sulks above absurdity was to enlarge and prolong them. If I didn’t speak another word all morning – no, all day – that would show them. At first they wouldn’t notice, then they’d be puzzled, then alarmed. By the evening everyone from our grandmother down to Patience, our little sister, would be pleading with me to speak, or tiptoeing about, consulting in whispers as to what should be done… But while we were running down the slope of the park to the edge of the lake, and making our way along it towards the weir and the bridge, I felt resolution failing: words and laughter were almost escaping. I stayed by the bridge to save what dignity I could. By the time I heard shrieks of ‘A hornet – look, a hornet!’ my immersion in the things I was watching had purged me of resentment so that I could run to see the hornet (there was a nest of them in one of the trees) without noticing that I had capitulated. I remembered it briefly that evening: a whole day – how it would have impressed them all! But what could I do about my own frailty?

Childhood is so often remembered as summery presumably because summer is the season allowing children in northern climates the most freedom: the longest holidays come then and they can be out of doors, away from the adult-organized house – most themselves. That water is so central is harder to explain. A classic Freudian interpretation is that water and sand represent urine and faeces, essential playthings because with them the child can act out infant fantasies … Can that be true? With us the fascination of water coincided through early childhood with an acknowledged interest in urine and faeces, so there was no need for the latter to appear under a disguise. When we were seven and five years old my brother (who was the younger) asked me: ‘Which do you like best, bigs or littles?’ I knew just what he meant: these things existed in our minds as a subject, in the same way that interior decoration might exist in the minds of adults. When he said ‘I like bigs best’ his preference left me incredulous, as though he’d said ‘I like garden gnomes’. To me littles was far more attractive – when I fell in love with the gardener’s ‘boy’ I imagined him urinating, and I went through a phase of doing it myself in odd places – under a corner of the carpet in the bedroom for example – leaving a few drops here and there like a dog establishing its territory. It did not occur to me that urine smelt: I was stunned when this habit was discovered, and so frightened and ashamed that I must have known all along that I was committing a bad breach of the rules, even though I hadn’t thought about it. I was caught while staying in an aunt’s house, and my flustered nanny shut me in my bedroom, where I waited for some unimaginable punishment contained in the thought ‘They will tell Mummy and Daddy’. I had never been smacked, never deprived of anything I wanted, never even sent to bed or stood in a corner – well, yes, stood in a corner once, but it seemed silly rather than mortifying. Adult disapproval was the only weapon used against me, so it was fully potent: the unimaginable punishment might, perhaps, be that my parents’ disgust would make them unable to love me.

My aunt came into the room. The only thing I was aware of was a longing to vanish. ‘You

are

a disgusting little guttersnipe, aren’t you?’ said the aunt, disdainful rather than angry. When I understood that I need expect nothing worse than that, my relief was so great that I could hardly comprehend it. My parents would never know! (When I was home again a doctor came although I wasn’t ill, and pronounced my bladder sound, but I didn’t connect the two events.) The incident soon faded – but I never again experienced the impulse to pee in corners.

No, the disturbances caused in us by water were not the same as the titillations caused by urine. Water inspired sensations of longing or impulses towards creativity (many dams were built). Water running shallow over pebbles, humped to the shapes of the stones; or over sand, trilling in minute puckers of ripple; water still and shadowy over mud, disorderly and silvered where it broke against an obstacle; water in muscular swirls and eddies: each of its moods had its own quality and evoked its particular response. It frightened only when in flood, yellow with soil, carrying clumps of scum, moving too fast. There was a terrifying book on the nursery shelves about the Mississippi in flood and a family of children swept away, clinging to the roof of their house … A stream in spate, even the disciplined stream which bisected the kitchen garden, was suddenly related to the Mississippi and became a threat – but a fascinating threat. Water linked with poetry rather than with sex.

Dabbling in streams was not the only way in which we expressed the urge to make things. When it came over us it was always the same – a strong, almost tormenting need to do something – but what? Often it short-circuited into bad temper: ‘What shall we do? – Mummy, we don’t know what to

do

.’ – ‘Why don’t you go and dress-up?’ – ‘

No!

’ … everything anyone suggested seemed futile. But usually the urge had its own solution within it, needing only to be recognized. Was this the house-building itch? No. Was it the dam-building feeling? No, not quite. Was it the signal for going over to the farm and finishing the cave we were digging into the side of a straw-stack? No-o-o … not today. What about making a pig-mush? Of course, that was it!

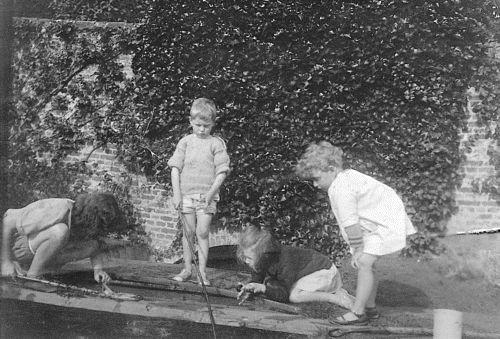

Fishing for newts in the kitchen garden

Making a pig-mush had to be done by Andrew and me alone, because no one else had quite the right feeling for it. We had been given an enormous old iron saucepan, now chocolate-coloured with rust, which we left lying about in the bottom orchard (the one for cooking-apples and quinces) for months between each pig-mush fit, and sometimes had trouble finding. The pig-sty was near the orchard, and first we would go and look at the pigs because it was necessary to work up a feeling of love and pity. Poor things.

Poor

things, in that stinking yard where the muck came halfway up the fence (pigs were not kept scientifically in those days). Nothing to do but lie about in that muck all day waiting for their food, and when the food came it was always the same: meal made into a sloppy porridge with water. Never mind, pigs, you’re going to have a treat now. We’re going to make a pig-mush for you, we won’t be long.

The basis of it, to give it body, was a few handfuls of the pigs’ own meal mixed with water in the usual way. The mush’s beauty lay in its other ingredients. Some were obvious, such as apples, carrots and wholesome-looking fresh green grass, but as the work progressed the creative fever would mount, and we would scurry about the garden and even up to the house, to beg from the cook. Six pink, six white, six red rose petals; a handful of mint; pinches of salt and pepper; some icing-sugar; two senna-pods (the taste would be disguised and they’d do the pigs a lot of good); a little duckweed? Why not. Then some crumbled Madeira cake and some asparagus tops, and two bruised peaches which had fallen off one of the trees espaliered on the kitchen-garden wall. We might even dare to pick a perfect one – a crime, but what an undreamt of delicacy for the pigs! It could take most of an afternoon before the saucepan was brimming and the feeling came over us that there wasn’t much more to be done to it now. Then a thorough last stirring, and it was carried to the pig-sty and balanced on the fence above the trough. The pigs would come surging and squealing, and there was an anxious moment before the pan was tipped: it would be disaster if the mush splashed uselessly over a pig’s thrusting shoulders instead of into the trough. An opening – quick! … and the mush would be poured. One panful between five or six pigs was gone in a flash, of course, but we were sure that quality made up for lack of quantity, and would stand gazing tenderly at the pigs, deeply satisfied at having gratified such an urgent need.