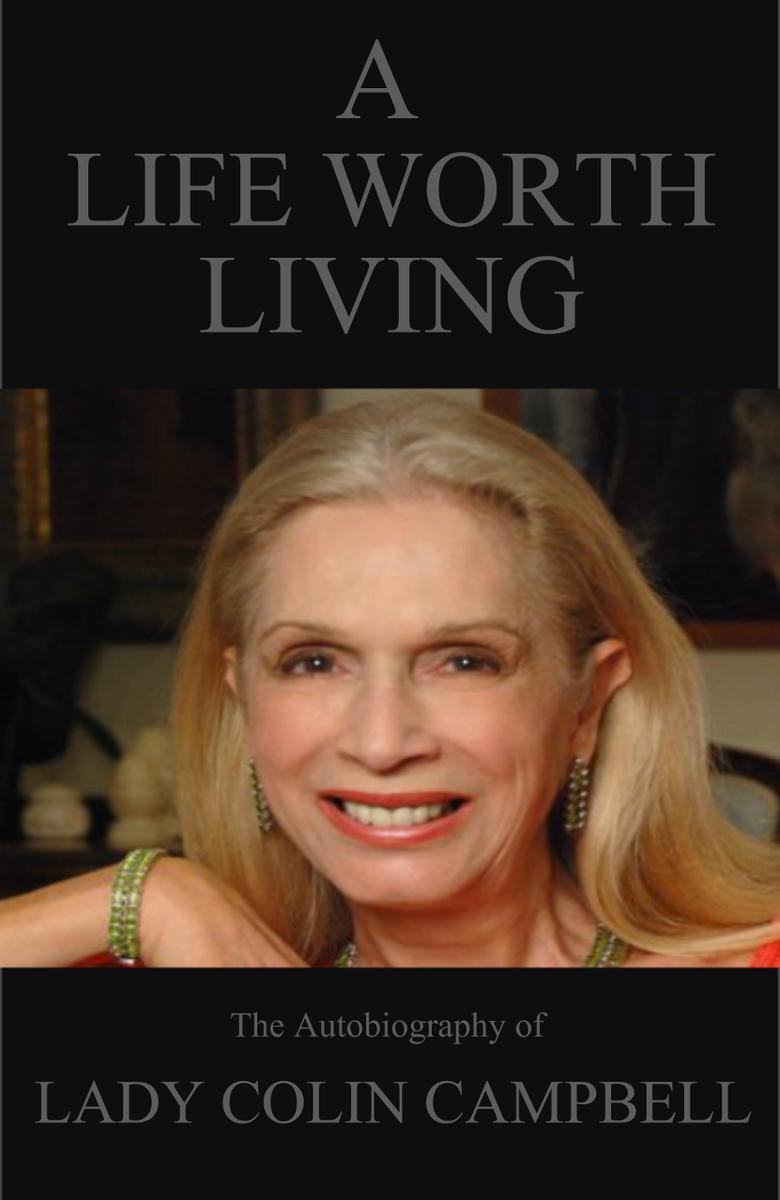

Life Worth Living

Authors: Lady Colin Campbell

“Truly thrilling…certainly a life worth reading” EVENING STANDARD

“Jaw-droppingly sensational” Lynn Barber, DAILY TELEGRAPH

“The author seems possessed of a joie de vivre which carries her through the strangest times … if one had a suitably flamboyant hat, one might very well be tempted to take it off to her.” SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

IFE

W

ORTH

L

IVING

The Autobiography of Lady Colin Campbell

This book is dedicated to my beloved sons, Dima and Misha

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

By the very nature of this work being an auto - biography, many of the people to whom I am indebted for the love, thoughtfulness, kindness and consideration they have shown me over the years, are mentioned in the forthcoming pages.

To them, and to those whose names have not been mentioned for one reason or another, I wish to say a massive thank you.

W

hen I was growing up, I could not understand why people always described my family as exotic. To me, they seemed perfectly ordinary. It was only when I was well into my thirties, and had a wide cross-section of people to use as a point of comparison, that I finally saw how truly unusual my antecedents were.

The family into which I was born, in St Andrew, Jamaica, in 1949, was one of Lebanon’s better-known Christian families. Phoenician in origin, Christian since the sixth century

AD

, until the eighteenth century the Ziadies were Maronites, the only branch of the Catholic Church which owes its devotion to a national saint and celebrates the Mass in Christ’s native tongue: Aramaic. The family’s exoticism is inextricably tied up with its roots. Being Arabic, even the name itself has six different but equally correct Romance spellings, depending upon which transcription you prefer. Originally, we came from Kesselwan. Many of my relatives still live there, or in nearby Jounieh, including the present head, Camille, the Christian senator for East Beirut.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, an ancestor left Kesselwan and moved to Choueifat. In those days, that town, which is now part of Ras (greater) Beirut, and which became famous during the Civil War as the site from which the Muslims bombarded Beirut Airport, was an important centre for the Silk Route. Between the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries, Choueifat was of greater significance than Beirut, which became Lebanon’s capital only after the Ottoman Empire collapsed at the end of the First World War. The key to why my-many-times-great-grandfather moved to Choueifat lies in the history of the town. Commerce was only one of the reasons for its ascendancy. The centre of the Greek and Russian Orthodox Churches in a country where religion and politics were inextricable, Choueifat was the place from which Imperial Russia attempted to acquire an outlet to the Mediterranean. This the Russians hoped to accomplish by strengthening links with the Orthodox community, the long-term objective being to supplant the Ottomans and turn Lebanon, or at least a part of it, into a Russian territory. So deeply entrenched did Russian influence in the area become that it eventually resulted in the Crimean War of 1854–58, in which Britain and France joined the Ottoman Empire to block Russian ambitions.

Politics and religion played their part in my family’s prosperity and ultimately in their exile. It was when my great-etc.- grandfather moved to Choueifat that our branch of the Ziadie family broke with the Maronites. Family legend has it that he and the brother who moved with him were compelled to do so because of involvement in a blood feud, but I believe that something much less glamorous was responsible: ambition. By that time the Ottomans had embarked upon a policy of

stamping out the culture and language of the Lebanese, of which the Maronites were perceived as the guardians, and any Maronite who wished to enjoy the many benefits of life under the Ottomans would surely have realised that he stood a better chance of doing so by moving away from a bastion of Lebanese heritage such as Kesselwan to somewhere like Choueifat. Here, Muslims and Orthodox Christians mixed more freely; religion, though important, took a back seat to commerce; Turkish authority was not so openly challenged; and there were even Lebanese, such as the princely house of Arslan, who were loyal to the Ottoman cause. Whatever the reason for the Ziadie brothers’ move from Kesselwan, they flourished. Soon they were well established, with comfortable houses and landed estates surrounding Choueifat. The change in religion proved useful, too, for one of their sons, the paterfamilias of the Ziadies of Choueifat, was created a Count of the Russian Empire by the Czar.

The family’s escape from the effects of religious unpopularity proved temporary, however. As the nineteenth century wore on and the European powers sought to lay down areas of influence within the Middle East, the Ottomans tightened the vice against those they regarded as traitors to their cause. Primary among these were the Christians, my family included. Nationalism was now a geopolitical fact of life. Both the Ottoman and Austro–Hungarian empires were involved in a literal fight to the death to keep the various nationalities under their mantles. Whenever the Ottomans wished to raise money or merely assert their authority, they would level punitive taxes against the subjugated nationalities such as the Lebanese. Christian and Muslim alike were beginning to suffer, and a level of co-operation grew up between all the religions. In each Ziadie house in Choueifat there was a large storage room for food beneath the kitchen. Beyond that was a secret room big enough to hide young men evading conscription into the Ottoman army, or wanted for crimes such as the desire to practise Christianity without fear of recrimination.

Between 1860 and 1890, the situation worsened to such an extent that my grandfather, George Ferris Ziadie, and his four brothers decided they would have to leave. This was a momentous and painful decision: not only would they be abandoning a prosperous life – my grandfather, for instance, was an architect with a substantial practice that took him to the far corners of the Ottoman Empire – but also one of the most beautiful countries on earth (the Garden of Eden was reputedly situated in Lebanon). Combining rugged mountains with the splendour of a dramatic Mediterranean coastline, in the winter it is one of the few places where it is possible to swim in the sea an hour after walking in three feet of snow in the Lebanese mountains, home of the biblical cedars. Moreover, the brothers would be leaving behind all the sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins who form such an integral part of Mediterranean family life.

The first to depart was Tewfik, who, according to family legend, was bound for America, but grew bored after making his way across Europe and over the Atlantic and decided to break his journey in Jamaica, only a few days’ journey away from his destination. Jamaica was, in many ways, an inspired choice. It

is more or less the same size as Lebanon, has a similar climate (albeit with no winter), and a geographical echo of his homeland in the lush Caribbean coastline and the magnificent Blue Mountains which divide the island in two. Exultant to have found a safe country so reminiscent of his own, Tewfik sent word to his brothers, George, Isaac, Adeeb and Alfred, who followed him there.

Life cannot have been easy for the emigrés. They spoke very little English and now had to eke out their living. But flowing in their veins was the blood of the Phoenicians, the creators of the concept of trade and the founders of the first alphabet and mathematics. Resourcefully looking around them, Grandpa Ziadie and his brothers saw a gap in the market. No one in business was catering for the average Jamaican black person: all trade was being conducted, largely by the Jewish community, for the white oligarchy or for the agricultural sector, the plantocracy. My grandfather and his brothers set themselves up as dry-goods merchants, opening shops in the capital, Kingston, which served the black people exclusively. Success was immediate, even if large profits were not – they operated on small margins. But the market was large enough to comfortably accommodate the Ziadies and the other Lebanese families who fled to Jamaica at around the same time, some from Choueifat itself.

By the time I was born, in 1949, virtually every shop and manufacturing enterprise in the country was owned by members of the Lebanese community. They were the single richest group in the country, and were perceived by the man in the street as wealthy beyond the dreams of avarice. This was a fallacy. Although wealthy by ordinary standards, we were hardly rich by the criteria of the truly rich, people like the Rockefellers or the Mellons. None of us, for instance, had a yacht that could sleep twenty, even if some of the family did have ocean-going boats and private planes that could seat up to four. What we did have was a comfortable way of life: ambassadorial style houses, immaculate grounds, servants, tennis or badminton courts, swimming pools, racehorses. My father, his brothers, and most of their first cousins owned enough racehorses to make us the premier racing family in the land. Several of the cousins had branched out into training as well, so no race meeting ever took place without several Ziadie horses running. This, together with the ever-present family name above the shops, gave us a high profile.

Six feet tall, with raven-black hair, hazel eyes and the pale skin of his Russian grandmother, my father, Michael George Ferris Ziadie, was devastatingly attractive to women. Handsome in the Cary Grant mould, he was also passionate, honourable and ostensibly easy going. Beneath that veneer, however, lay a volatile and sensitive perfectionist who was a soft touch for any hard luck story. He stuttered badly, with the result that he was a man of few words, but he was an omnivorous reader and highly intelligent, and whatever he did say was worth hearing. Perhaps his most striking attribute was his complete naturalness. Like many gentlemen of the old school, he treated princes and paupers with absolute uniformity, and was impressed by nothing but character.

When my father was twenty-six, he met my mother. Gloria Dey Smedmore was fifteen at the time of that first meeting. Sixty-two years later, he reminisced, ‘I fell in love with your mother the first time I saw her. Her uncle, John Burke, introduced us. She was young, but she was no little girl. She was a beautiful young woman, and very, very entertaining. She captivated me totally with her personality. I loved her then, and I love her now.’

Red-haired and brown-eyed, Gloria was one of those lucky girls who had long, slim legs and a slender build crowned with a full bosom. My mother was related to four of Jamaica’s oldest families, and to say merely that she was out of the top drawer would not convey the quality of her breeding. Her father was Lucius Dey Smedmore, a gentleman of such fine social sensibilities that the word snob would not begin to describe the niceties by which he lived. I loved my grandfather and his brothers and sisters, but I must confess I could never understand why they were generally acknowledged as social eminents. The whole scenario struck me as typical English hogwash: assert that you’re great for long enough, and everyone will believe it. It seemed to me as if they had never had anything to recommend them except for impeccable manners and an outstanding belief in their own superiority. They had never had a huge amount of money, even before my great-grandfather somehow allowed a solicitor to fleece him of what he did have. They owned no large estates, had no great titles, occupied no significant political positions. They did own a magnificent townhouse in Kingston, which was built, Roman-style, around a courtyard garden – the dining room alone was about forty feet long, and stuffed full of the finest antique furniture – but their most outstanding feature, aside from their niceness, was their position in society.

My maternal grandmother, May Burke, on the other hand, came from a genuinely aristocratic background, which even her disparaging grandchildren acknowledged. On her father’s side she was descended from the earls of Mayo, an Anglo-Irish family which gave India its first viceroy. On her mother’s side, Grandma was a member of two of the western world’s most eminent Sephardic families: the de Passes and the Lindos. (It was at the house of a distant cousin of mine, Commander Robert de Pass, that the Prince of Wales met the adult Lady Diana Spencer, who was a good friend of his son Philip.) The Jews were the true aristocrats of Jamaica, for they were the first settlers, having been induced by the Inquisition to leave Spain and Portugal – in the early sixteenth century, Jews were given three options: convert, emigrate, or burn. Only in the West Indies were they free to practise their religion, with the result that Jamaica has the oldest colony of Jews in the western world. Moreover, the Jewish community has remained consistently prosperous throughout the centuries, and they are so highly regarded that anti-Semitism is not an intelligible concept to Jamaicans.

After three years’ courtship, my father asked my grandfather for my mother’s hand in marriage. Although Grandpa gave his consent, he was disappointed that Mummy wanted to marry ‘a Syrian’, and incited his brother Julian to snub Daddy when the engagement was announced. Rather than shake his hand, Uncle Julian turned on his heels and walked away. To his

credit, Daddy never let such pettiness bother him, nor did he hold it against either brother. My grandmother, however, had no misgivings about the match. As she was partly Jewish herself, and had a healthy respect for ‘a handsome devil’ and a good bank balance, she willingly gave her consent with the words she would never live down: ‘If you wanted to marry a horse’s head, that would be fine by me, as long as you loved him.’

Religion now became an issue. Since the move to Jamaica, where there was no Greek or Russian Orthodox Church, the Ziadies had reverted to their original religion, Catholicism, and would sooner have died than gone against any of the Church’s teachings (adultery, fornication and gambling excepted). The Smedmores, meanwhile, were one of the staunchest Anglican families in the land, and my grandfather was the latest in a long line of Smedmores to sit on the governing body of the nation’s established Church. It would have been as unthinkable for Mummy to convert as for Daddy to marry outside the faith, so a compromise was reached. They married in the Roman Catholic Cathedral, Mummy having signed a document undertaking to bring up all their children as Catholics.

Within fifteen months, my brother, Michael Anthony Ziadie, was born. A year and nine months later, what should have been a bundle of joy, but turned out instead to be a load of trouble, arrived on the scene. To say that my birth was a mixed blessing would be to stretch the truth to breaking point. I was a sickly baby who hovered between this and the afterlife for several months. But that was the least of the problems, for I was born with a cosmetic malformation which led to me being registered as a boy, and given the names George William.

The reason why I was not registered as a girl is simple. No one knew I was one, because I was born with fused labiae and a deformed clitoris. As anyone who is familiar with infants knows, the genitalia of new-born babies are out of proportion to the rest of their bodies. This phenomenon is, presumably, nature’s way of hitting you in the face with the sex of your child. But nature is not an exact science, and mistakes do occur.