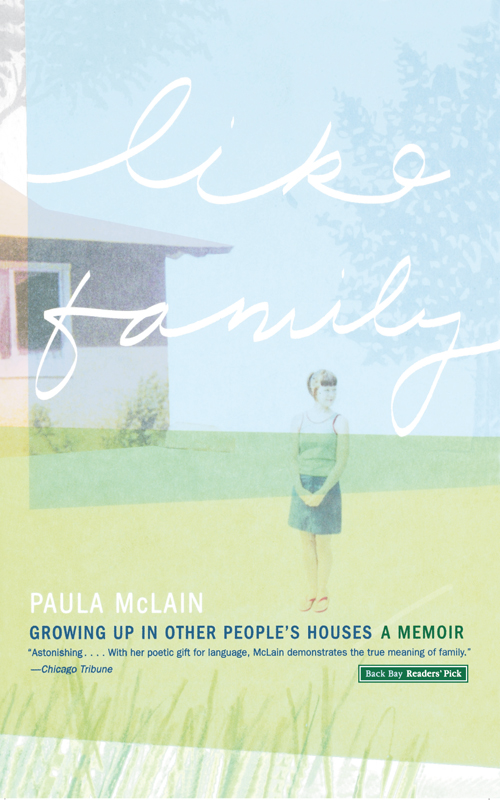

Like Family

Authors: Paula McLain

Acclaim for Paula McLain’s memoir

GROWING UP IN

OTHER PEOPLE’S HOUSES

“Astonishing…. With her poetic gift for language, an extraordinary frankness, and narrative generosity, McLain demonstrates

through the impenetrable bond with her sisters the true meaning of family.”

— Kera Bolonik,

Chicago Tribune

“A powerful and haunting memoir.”

— Anne Martiro,

Ann Arbor News

’If every memoir were like Paula McLain’s

Like Family,

there would be far fewer accusations of navel-gazing made against the genre. That’s because McLain, who writes about the

years she and her two sisters spent bouncing around the foster-care system in the early seventies, is sharing something much

more illuminating than a string of bad relationships or a substance abuse problem. McLain’s voice is deft and often humorous

as she limns the profound moments of sadness and strange exhilarations of her rootless youth. While the subject matter pierces

your heart, McLain refuses ever to play the pity card, and her clear-eyed approach opens our eyes to the strange subculture

of ‘lost’ children. A sometimes startling, always engaging view of the hidden world in our own backyard.”

—

Elle

“ Like Family is

a personal triumph…. McLain’s story is one of nobility and of the strength of a young woman’s spirit.”

—

Wisconsin State Journal

“ Ms. McLain’s close observation of the sisters’ perils jumps with life and wry merriment. They take their pleasures and their

sorrows as they arrive; even their times of desolation are narrated in language that conveys a kind of ragged glory — the

tattered flag of their kinship still waves!”

— Paula Fox, author of

Borrowed Finery

and

Desperate Characters

“McLain’s childhood was rich in adventures and encounters with odd pseudo-relatives, and she unstintingly recounts them in

vivid detail.”

— Carolyn S. Briggs,

Miami Herald

“Like Family

isn’t written to shock. McLain tells about the horrors gently, edging toward them through the vivid and universal landscape

of childhood, with its intense sensations, its pleasures of taste, sight, and smell, told through the particulars of their

Fresno, California, childhood…. The memoir shows a poet’s touch…. How did McLain survive her childhood and grow into a woman

well-balanced enough to look back and write about it so vividly and gracefully, with no evidence of self-pity?”

— Polly Shulman,

Newsday

“An unsentimental and thus telling memoir…. A thoughtful recalling of the emotional toll a life of uncertainty can take.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

“A heartbreaking memoir.”

— Sherry Amatenstein,

Woman’s Own

“McLain displays her poetic inclinations with florid descriptions…. A brave account.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“What makes

Like Family

so remarkable are not the peculiar circumstances of Paula McLain’s childhood but the depth of understanding that she brings

to those circumstances, and the beautiful prose in which she renders that understanding. Seldom have I seen so vividly evoked

the need to belong to some, any, kind of family and the painful negotiations that time brings to even our closest intimacies.”

— Margot Livesey, author of

Eva Moves the Furniture

“The first thing that strikes the reader about

Like Family

is that the author has chosen her words very carefully, fastening her story to a spectacularly stark but beautifully resonant

prose…. McLain reveals in waves of childhood memory what it was like to grow up in foster homes, buffeted from family to family,

never quite feeling at home…. It is the mixture of sweet nostalgia for growing up, combined with the harsh emotional scars

of neglect and abuse, that make this book remarkable. McLain leaves the reader knowing that a child is not the sum total of

the abuse she experienced at the hands of others, but somewhere, between the neglect and the mistreatment, a child is able

to create a space and a life that is her very own.”

— Kathleen O’Grady,

Bust

“This book has a power of its own — the raw force of a memorable and well-told story of children who overcome the injustice

of their abandoned state and grow up to fashion some sort of reasonable adulthood for themselves. You’re likely to have a

lump in your throat by the end of this gutsy and honest tale.”

— Pat MacEnulty,

Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel

Less of Her

Copyright © 2003 by Paula McLain

Reading group guide copyright 0 2004 by Paula McLain and Little, Brown and Company (Inc.)

All rights reserved.

Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: September 2009

Author’s Note: This is a work of nonfiction. The events and experiences detailed here are factual and represented as faithfully

as possible according to my memory. In many cases, time frame and place-names have been altered, and virtually all names of

individuals — aside from my own and those of my sisters — have been changed in order to protect their privacy.

The author is grateful for permission to use the following: “Without Rings” by Neil Young, 0 1998 Silver Fiddle, all rights

reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. The poem by Emily Dickinson on page ix

was reprinted by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from

The Poems of Emily Dickinson,

Thomas H. Johnson, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1951, 1955, 1979 by

the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08266-2

Contents

Acclaim for Paula McLain’s memoir

Questions and topics for discussion

Paula McLain’s suggestions for further reading

For my sisters

and

for Connor

What fortitude the soul contains,

That it can so endure

The accent of a coming foot,

The opening of a door!

—

Emily Dickinson

I’m picking something up.

I’m letting something go.

Like a dog, I’m fetching this

to you.

— Neil Young

D

OGS ARE EASY

. I

F

their tails are up and their eyes are soft, you’re in. Sometimes they need to smell your hands, your shoes, between your

legs. Sometimes they just throw themselves full tilt, all of them at all of you — like the Lindberghs’ dogs. They were what

we saw first, a happy blur along the fencing as our social worker, Mrs. O’Rourke, slowed the car and stopped in front of a

whitewashed wooden gate. Teresa got out to open it, her sneakers sending dust. With one hand on the metal latch, she pointed

to a sign that hung from the center of the gate and spelled out, in blocky white letters,

LINDBERGH ACRES

. She grinned, flashing her chipped front tooth, and ran back to the car. “They named it,” she said, crawling in beside me.

“Just like Big Valley.”

The brown ranch house squatted on a low hill. Dry grass stretched to every side and looked, from the car, like giant slices

of toast. How different it all was from the Spinozas’ boxy row house in central Fresno; the Clapps’ well-groomed lawn and

portico with a blinding-white Cadillac; the Fredricksons’ Palo Verde tract home. The driveway here wasn’t concrete but dirt,

with deep potholes and stones. To the left stood a large pasture where several horses lumbered behind an electric fence.

Horses! To

the right, fields and fields, mushrooming fig trees.

The Lindberghs’ house was ringed by an oval of split-rail fencing and a lawn that looked determinedly untamed: crisp brown

around the edges with crabgrass and clover erupting every few feet like acne. It was late afternoon, and the family had come

out onto the lawn to greet us. Bub and Hilde both wore new dark-blue jeans, cowboy boots and dress-plaid Western shirts with

pearly snap buttons. Their seven-year-old daughter, Tina, did an anxious series of little hops forward and back, looking,

with her cap of straw-colored hair, her yellow shorts set and bare feet, like a round yellow bird. She was getting sisters.

We had been promised to her, and here we were.

If there’s anything odder than being introduced to your new family of complete strangers, I don’t know what that might be.

The social worker sticks around for a while, trying to break the ice, but when she leaves, it’s just you and your questions,

popping like flashbulbs, and these people who will sit you down and feed you dinner and show you to your room. In that way

it’s like a hotel because nothing belongs to you. It’s all being lent, like library books: the bed, the toothbrush, the bathwater,

the night-light under the medicine cabinet that will help you recognize your own face at 2

A.M.

when you get up to pee.

As I stood on the Lindberghs’ lawn next to my sisters, it occurred to me — for the first time — that the families who took

us in were being introduced to absolute strangers too. The big dogs danced and squirmed, gleeful with new smells, but Bub

and Hilde held as tight and still as a pair of garden gnomes. They didn’t know what would happen; they didn’t know the first

thing about my sisters or me — what we’d say or do, if we’d stay for a month or a year or three. And us, we’d seen the backseat

of Mrs. O’Rourke’s car too many times, our clothes in garbage bags on the floorboard. If we felt any hope that this new situation

would be different, then it was the stowaway version, small and pinching as pea gravel in a shoe. Bub and Hilde seemed nice

enough, but didn’t everybody at first?

Mrs. O’Rourke’s car warbled down the drive, tires falling into every third pothole. We watched until she was out of sight

and then watched the empty road. Finally, there was nothing to do but turn toward the Lindberghs. We stood, the three of them

and the three of us, on the grass dry as cereal, and the noises all around — the snuffling dogs and the buzz of the air conditioner

and the sprinkler pelting a row of yellow roses — seemed to be saying,

Now what? Now what? Now.

T

HE

L

INDBERGHS

LIVED WAY

out of town in Ashland, California, which is right next-door to Fresno in the San Joaquin Valley. You’ve probably heard of

Fresno, it being one of the likeliest places to get shot in the head in a dark alley and also the raisin capital of the world.

Penny and Teresa were born in Spokane, Washington, where our mother is from and where she went for help when our father ran

off and left her midpregnancy, as was his habit. With my birth, she didn’t have to go to Spokane because her mother came to

her, and so I was the one delivered in a Fresno vineyard — or rather in a hospital wedged between vineyards. The place was

tiny, and since no rooms were available when my mother’s time came, she labored in a hallway next to the washer and dryer,

panting and contracting while a load of sheets twisted and filled with sudsy, grayish water, shutting her eyes against nausea

when her mother offered her quaking cubes of strawberry Jell-O. This was in October, past the drying season, but I’ll bet

the air around the vineyards still hung with the sickly sweet smell of grape funerals. It’s all the juice that does it, sugar

collapsing on itself as the grapes shrivel into shrunken little heads. It stays and stays, that smell. You keep thinking you

can blink it away or swallow it down, but you can’t.