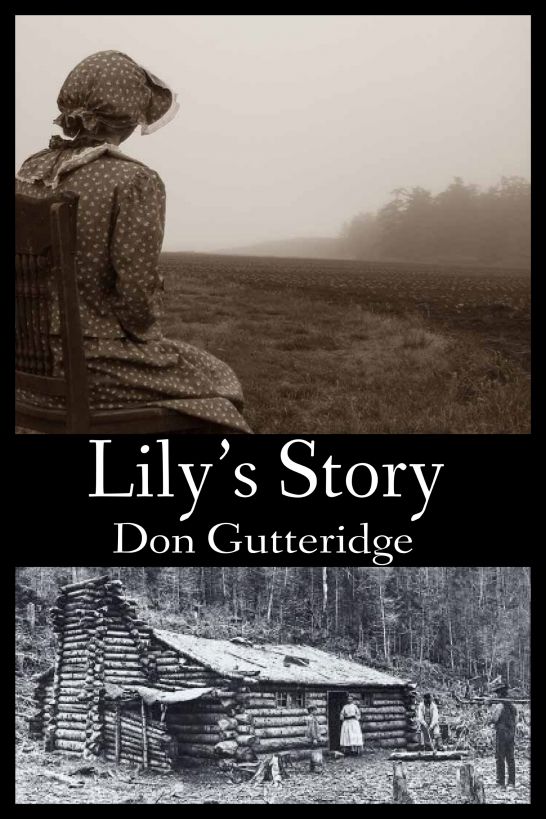

Lily's Story

Authors: Don Gutteridge

Tags: #historical fiction, #american history, #pioneer, #canadian history, #frontier life, #lambton county

Lily’s Story

By Don Gutteridge

Published by Bev Editions at

Smashwords

ISBN:

978-0-9916798-9-8

Copyright 2013 Don

Gutteridge

Smashwords Edition, License

Notes

This ebook is licensed for your

personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given

away to other people. If you would like to share this book with

another person, please purchase an additional copy for each other

person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it

was not purchased for your use only, then please return to

Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting

the hard work of this author.

GUTTERIDGE /

Lily’s Story

LILY’S STORY

A Novel

by

Don Gutteridge

Bev Editions

For my Aunt and Uncle

Betty and Bob Gutteridge

of Point Edward

In loving memory

Table of Contents

St. Vitus Dance

Lily

Moore Township, 1845

Something stirred in the darkness ahead. It

made no sound, as yet. But it was present, and alive, or coming

alive: she always knew. She did. The breath from a fawn’s cough

could tease her skin – like this ripple of shaded wind against her

cheek – long before her ear caught the sound and recorded it. Lil

was glad once again to be in the comfort of the trees’ canopy. It

was cozy here, like the cabin with Papa’s fire blazing out of icy

logs, when Mama was not in her bed. Lil wasn’t afraid of the dark.

Mama sometimes shivered in the dark at night, the rare night when

Papa “was off” and Lil was beckoned to press her thighs and chest

and swan’s belly against her mother’s clenched form. She dreamt she

was a moth spinning a cocoon of silver words about them both, full

of charms to drive the gremlins from Mama’s eyes, while outside,

heard only by her, the snow sang to the wind and no one in the

world was lonely.

It was never lonesome in the bush. Here

things bulged and endured in the dappled undergrowth – ferns and

worts and fungi and mosses, and, in the few random spots freckled

by sun, surprised violets. They made their voices known. Lil could

hear them already though she was moving with short quick steps

towards the deepest cove of the back bush, the place forbidden by

Mama, the home of the almost-sound that vibrated the air with

furred bat-wings and no eyes. She stopped. Beyond, a branch

stretched, umbilical and biding. Ferns sighed in currents only they

could feel. A thrush untangled his song: pastel and longing. Lil

set her face against the tiny drafts of air raised by her own

body-heat. A snakeskin combed the grass; she heard a birdwing flex

and fold, a deermouse scuttle and freeze, a caterpillar dissecting

a resistant leaf. The sound had stopped.

You stay away from the Indians, you hear?

Mama said so every day. Mama hated Indians. They were the cause of

everything. They took whiskey; they went crazy and hurt people;

they never did a lick of work; they went off hunting

god-knows-where in the back bush, taking good men with them, so’s

the trees didn’t get cut. And them squaws, Mama would say in a

special voice, her eyes getting fiery and pure, why they – she’d

look at Lil and stop, and the passion would ebb from her face.

Well, they’re wicked, Lil, they take whiskey and – dance and do bad

things with men… Lil would be trembling with anticipation at seeing

her mother’s pale flesh puff out with some kind of necessity beyond

self-preservation. Lil wanted to ask, not about the bad things, but

about the dancing. Though she never did. It was after one of these

bouts that Mama often took to her bed.

But Lil knew where they stayed. Many nights,

curled in the straw of her loft, she heard the drumbeats come

across the tree-tops from miles away and settle into their clearing

as if they had been aimed there. They were not like her heartbeat,

back and forth, nor like the sprightly songs Mama sang in her other

language when she was “feeling better” and sitting before her

spinning wheel in the bright sun of the garden she had helped to

clear. It was a pounding, repetitive music that set her heart ajar,

that made her dream of strange creatures who preferred breathing in

the dark, that made her long to know what words would be sung to

such cadence, what dances would find their feet in such grooved

frenzies. She wanted to see these women, how they moved in the

firelight that twisted above the black roof of the bush, what their

eyes did when they danced in their smoky, burnished,

mosquito-driven dark.

An axe rang against a

tree-trunk, clear as a church bell.

Papa’s

back

. Lil recognized the signature of his

chopping: two vicious slashes, the second slightly more terrifying

than the first, followed by two diminished, tentative ‘chunks’.

Maybe Mama would hear it and leave her bed. He was in the North

Field. That was good. He’d only “gone off” as far as the

Frenchman’s. Sometimes one of the Frenchman’s boys came back with

him and helped Papa. Lil hated them, all three of them. They

watched her all the time with the edges of their eyes. And Papa

would shout at her to go away. Sometimes though he brought Thérese

back. Lil liked Thérese though she talked crooked and had an ugly

belly that poked out in front of her like an old melon. Thérese

cooked soup, made bread in the mornings, and laughed. She was

happy.

Thérese showed Lil how to skip. She put a

small tin instrument to her mouth and made music. She laughed when

Lil hopped and jigged, and then Papa came along and took her by the

hand and swung her about in the midst of the music, and laughed

from the back of his throat. “Well, my Lady Fair Child, so you can

dance, eh? We’ll have to take her down to London to see the Queen,

won’t we, Thérese?”

Thérese got pains in her ugly belly, though,

and had to go back to the Frenchman’s.

“

She’s dead,” Papa said,

that evening, standing in the open doorway, his hands helpless.

“The babe, too.”

“

All for the best,” Mama

whispered from her bed. “Whose was it?”

“

Luc’s I guess. The

eldest.” Papa did not see Lil at his knee peering up with the

question “What’s dead?” on her lips. “

God

damn them all, may they rot in hell,

” he

hissed in a voice that came from nowhere inside him Lil had ever

known.

Papa was back. Every day he swore he would

“kill that damn Frenchman”, but all the same he went over there.

Though Mama didn’t mind too much. It was the Indians she hated.

Whenever Papa “went off” in that direction – through the East Field

to the back bush, where Lil was at this very second – Mama got

mean. So Lil would look for berries along the edges of the cleared

area, and when she got back Mama would be in her own bed in the

curtained-off area to the right of the fire, her body folded on the

straw pallet, rigid as a pin.

For a moment Lil thought she ought to go

over to the North Field. The place where the Indians were was

forbidden. The strange sound she thought she had heard had stopped,

or never been. Papa might be in a good mood. She listened carefully

to the desperate repetition of Papa’s axe against the grained flesh

of the tree. He was at one of the hardwoods again. She would not

go. Though she wanted so to dance for him again, the way Thérese

had showed her, to have Papa laugh and say “Lady Fair Child, may I

have the pleasure of the next dance?”

Suddenly the axe-blows ceased. Lil held her

breath. Then she heard the thunderous, sustained shriek of

disbelief and betrayal as the two-hundred-year-old walnut came

crashing through the forest to stun the ground with its abrupt

goodbye. Lil sat for a while in the sun-lit beaver meadow below the

creek and listened to the tree’s dying reverberate through the

earth.

She hated him. He trapped rabbits in the

east corner, their strung-up bodies stiffened by the night air, the

warmest morning could not thaw them. He nailed the head of the

dear-with-no-eyes above the fireplace, where it stared down at them

pretending to see like Old Samuels, the blind Indian who sometimes

sat in the sun in the dooryard, telling stories to the Frenchman’s

boys and twitching his white head about from person to person as if

it could perceive the smiles and nods of an audience. She hated

Papa. He made Thérese “be dead”.