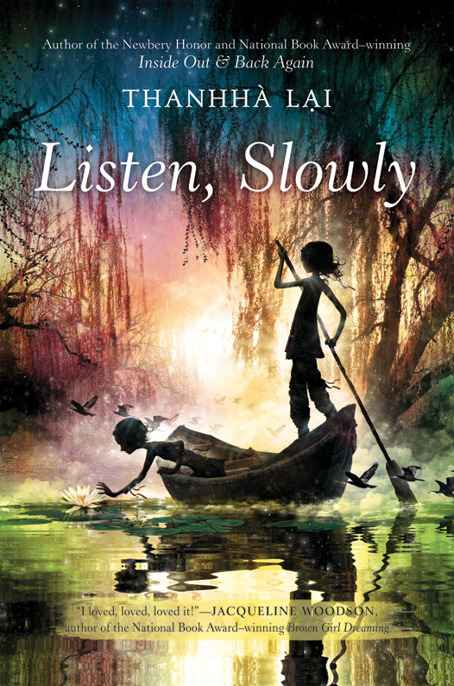

Listen, Slowly

Authors: Thanhha Lai

For AnAn and her Bà

CHAPTER 1

I

whip my head toward the airplane window as soon as Dad scoots into my row. There’s nothing to see except clouds and more clouds, but anything is better than looking at his fakey sorry-to-do-this-to-you face.

Dad is waiting for me to turn toward him. Yeah right. One little glance would encourage another diatribe about connecting with my roots. They’re

his

roots, not mine. I’m a Laguna Beach girl who can paddleboard one-legged and live on fish tacos and mango smoothies. My parents should be thanking the Buddha for a daughter like me: a no–lip gloss, no–short shorts twelve-year-old rocking a 4.0 GPA and an SAT-ish vocab who is team leader in track, science, and chess. I should at least be able to spend the summer resting my brain at the beach. Instead, I get shoved on this predawn flight.

My parents slapped me with the news just last night when I was floaty and happy because sixth grade was finally over. I was thinking summer vacation, sunsets, bonfires. But noooo, with buggy eyes and stretchy smiles, they cooed out the news that I “get to” escort Bà, Dad’s mom, back to Vietnam for six whole weeks.

“Bà needs you,” Dad said when I complained.

Dad goes to Vietnam every summer already, but he’ll be too busy hiking toward the most remote mountain to set up a one-man surgical clinic to fix cleft palates and acute burns. I hinted that perhaps he could skip this year but Dr. Do-Gooder shriveled me with facts. Apparently, the kids with hand burns suffer excruciating pain and can’t extend their fingers because the skin has shrunk. The ones with holes in the roofs of their mouths live with food and water gushing out their noses. Dr. Do-Gooder always has more demand than he can handle, so at the end of each trip he holds a lottery to pick the next set of patients, who spend a year anticipating his return. Every June, the chosen kids and their extended families travel for days to reach his clinic, forsaking their crops and animals. Surely, I cannot expect him to disappoint them.

Guilt, very big in my family.

Then it was Mom’s turn. She too talked about roots and blood then continued ad nauseam about accepting what’s embedded inside one’s soul, blah blah blah, before letting it drop that, much to her regret, she can’t go to Vietnam at all. Something about a trial she’s waited three years to prosecute. She’s known for always taking on the most brutal crimes against women. Halo, halo.

This is the summer I’ve been waiting for my whole life. At twelve, I’m finally old enough to take the shuttle to the beach without an adult sticking to me. My best friend Montana and I already got our hair highlighted and bought new swimming suits, hers a bikini with a pink bow smack on her butt, and mine a padded tankini because I have a boy’s body. I wouldn’t care except Montana thinks not having boobs is like not having hair. She’s very proud of hers, but that’s like being proud of a sunny day in Southern Cal. As if she did anything to make it happen.

I tried really hard to counterargue with Mom that I too must stay in Laguna; I too must see a project through. But how can I go up against Orange County’s golden prosecutor? It didn’t help that I had to be vague because I’d die before confessing there’s this boy. I can’t even think about HIM or I’ll explode with anxiety. I noticed HIM as soon as HE went on and on about this poem in class, and after that my stomach flipped like a dryer every time HE was around. HE does have these curls at HIS shoulders, as if that explains anything. I know HE’s going to hang at Anita (that’s a beach) all summer, and I promised myself I would start a real conversation and actually look at HIM. I have never said HIS name out loud and certainly not to Montana. She has a very bad habit of liking the boys others like first, and those boys have a very bad habit of liking her back.

After I got nowhere with my parents, I screamed and stomped to my room and slammed the door and threw books against the wall. That last part killed me—I love books. All that drama did nothing.

I’m on a plane.

Dad takes my chin, twists my face toward his and forces eye contact. “I know we’re asking a lot of you, but think beyond yourself for just a little while.”

I get that my preteen anxieties can’t compete with Bà’s classic suffering. After all, she lost her husband in THE WAR, which I always think of in all caps. Still, selfish or not, I’m going home as soon as I can maneuver around the sad saga of Bà.

If you think of Bà, you automatically think about Ông, my grandfather. The two always go together, Ông Bà did this, Ông Bà did that. Like saying Mom Dad. Ông was missing in action, so Bà raised seven children on her own. She got them here, pushed them through school, ended up with a doctor, four engineers, a professor, and an accountant. She never asks for anything. Still, my parents and uncles and aunts keep giving her everything. Sweaters, bathrobes, soft house shoes, comfy walking shoes, heater, fan, scented lotion, unscented lotion, big-screen TV because her eyes are failing, back to small-screen TV because the big screen made her dizzy. Endless.

It’s hard to believe that Bà would insist on anything, much less on a trip all the way across the world. She has lived with us forever and I’ve never known her to ask for so much as a glass of water. She hand sews her own clothes, always brown, always cool and soft, washes them in the bathroom sink, dries them in the bathtub, cooks her own rice and tofu and greens, puts them in cute glass containers stacked in the square refrigerator in her sitting room, where she has a tiny toaster oven and a one-cup rice cooker. She rarely leaves her corner of the house.

“Mai, try to understand that this trip is for you too. To see where you’re from . . .”

“AAAAHHHHH!” I scream into the airline pillow but immediately throw it down. I’m sure it’s infested with lice and stuff.

My scream got to Dad. He’s batting his eyes so fast you’d think a bunch of gnats just flew into his eyeballs. Holding in anger, he’s squeezing his voice through clenched teeth: “Bà has personal reasons to return home this summer.”

“What’s so important? All her children and grandchildren are in California. Her life is there. My life is there.” I’m loud but don’t care.

“Bà has had questions for decades. Be with her as she finally accepts . . . I thought she already did, but that quack calling himself a detective wrote her. I seriously doubt it’s possible but . . .”

“What are you talking about? What quack detective? I still don’t get why we have to go to Vietnam.”

Dad hisses, “Bà thinks Ông might be alive, that’s why.”

There’s no way Ông is alive. I’m being logical here. Bà can be wishy-washy, and Dad can indulge her all he wants, but facts are facts. Why am I the only one to understand that Ông is gone?

I’m trying to call Dad over to me but, of course, now that I actually want to reason with him, he’s at the back of the plane, pressing his index fingers to an elderly passenger’s temples to ease nausea. All kinds of people have their hands up waiting for his magical doctoring because they saw him care for Bà after she stirred in the row in front of me. She even got another big blue knockout pill. I asked, but no, I’m meant to endure the longest flight ever fully conscious. BTW, each of us gets a whole row because the plane is so empty. That’s how many people are dying to fly to my parents’ beloved birth land.

The sooner Dad can convince Bà that Ông is truly gone, the sooner we can whip back to LAX. He should just come out and say it. She’s usually the most practical person I know, saving every leftover grain of rice for the backyard birds and brushing her teeth with exactly half a cup of water.

Ông was listed as missing when Dad was two. THE WAR dragged on some more before ending on April 30, 1975. My parents have tattooed that date on my brain. Every year, they still do a ceremony for The Day Saigon Fell. It’s been thirty-five years, still . . . solemn faces, solemn faces. I’m shocked they didn’t name me April30, instead of Mai (at home) / Mia (at school). Believe me, they are still patting each other on the back for that clever flip. Bicultural, they tell me and beam. I didn’t have the heart to tell them I’m uni-cultural. I will, though, as soon as I land back on surf and sand.

Ông has been gone for decades, so long that his youngest child, my dad, now has gray hair. Even if Ông were still alive, and that’s a gargantuan

if

, wouldn’t he have found Bà by now? As a man of science, Dad will have to concede to the only rational choice left: sending me and Bà home.

Finally, Dad returns. “Why aren’t you asleep?”

“Did I get a big blue pill? I don’t think so.” I can’t help that my voice does a sassy singsong.

“Don’t talk like a girl with a runaway tongue, you know better.”

“All I said was . . . never mind. There’s no way Ông is alive.”

“Bà is the one who thinks Ông might be alive,” Dad says, a bit exasperated. “When I see that quack detective, I’m going to—”

“Gag him with pills?” I can’t help but interrupt. I could say so much more, but control. “So the detective has to convince Bà that Ông is gone, right?”

“Right, as soon as she accepts that Ông is truly gone, you both can go home. Mai, I would just like you to be with her until she accepts. All her life this has been her one wish, to be able to accept his passing. What kind of a family would we be if we deny her that?”

OMG, Dr. Do-Gooder just gave me my ultimate wish. I can just kiss life right now. My heart is bouncing so high it might booong out my mouth. I could be at the beach in three days, four at the latest. We will land in Vietnam, Ông will not be there to greet us, we will cry and light some incense, then home home home. I’m trying not to dance. This is a solemn moment.

“It’s heartbreaking for Bà,” Dad says. “I didn’t know my father to miss him and I feel guilty that I don’t feel something more. All my life, though, I’ve tried to imagine what it was like for Bà. They had been promised to each other since he was seven and she was five.”

“I’ve always thought the whole thing was so weird. Was that even legal? What if they grew up and really really didn’t like each other?”

“Not those two. Their parents must have predicted how they’d be.”

Just then, the rims around his eyes turn pink. For no reason Dad reaches out and hugs me, smooshing my face against his vest with too many pockets. I’m so startled I hug him back, inhaling harsh soap and sour sweat and mediciny medicine. Just as suddenly, he gets up and goes to his row.

I’ve never thought of this before, but what if Dad went missing? I’d leave for school one day waving bye, to realize later that was the last time I’d ever see him. The idea shocks me so much I sit numb for a long while. I think I would miss him to the point where my insides would disintegrate and leave a charred hole.

T

hings are looking up. We’re at a stopover in Hong Kong, which is fifteen hours ahead so we’re already on day two of this supposedly forty-five-day trip. Trust me, I will be trading in my return ticket much sooner than that. Dad, as usual, is off helping someone with something urgent.