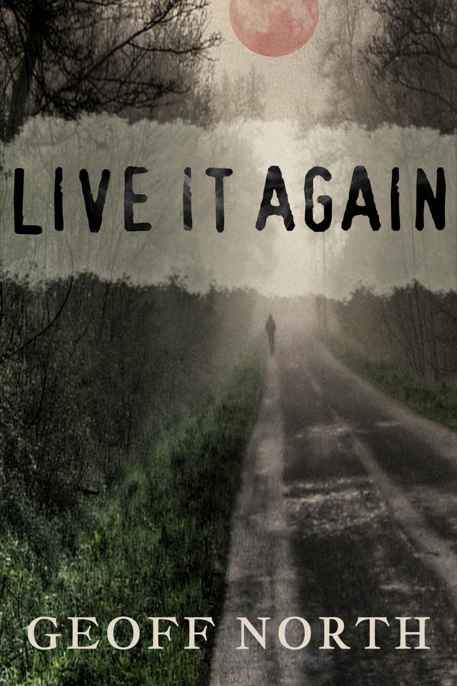

Live it Again

Authors: Geoff North

Live

it Again

By

Geoff North

Copyright © 2011

By Geoff North

Cover art by Keri Knutson

Formatted by Christine Rice

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. Reproduction in whole

or part of this publication without express written consent is strictly

prohibited.

For all those grown-ups that wished they knew then what they know

now—this is for you.

2011

Friday November 25

A warning. Metallic letters in glaring

yellow, outlined in orange. Rivets running through them vertically, covered in something

dirty and grey like ash. Hugh Nance saw the letters flash through his mind but

for an instant. A blink of his eyes and a quick shake of the head and the image

vanished. Not even enough time to register what it had said, but he knew

instinctively what it was. A warning.

He was still standing over Bob Richard’s

desk. His right hand clenched into a fist where he’d banged it down in

frustration just moments earlier.

“Are you finished?” The store manager asked

quietly.

“We’ve been friends since we were kids, how

can you do this to me? To my family?”

“If it were totally up to me I wouldn’t

have cut your hours at all, maybe a cut in salary, but you know how the economy

is.”

“The economy. Don’t give me that shit. This

is Braedon, for Christ’s sake.”

Bob reached across the desk and picked up a

handful of papers from a black plastic tray. “Take a look at these invoices. We

may be the only major grocery store in town but that doesn’t mean our business

hasn’t taken a serious hit in the last couple of years.” He plopped them down

facing Hugh. “Monday’s bill was less than seven grand. That’s everything,

Hugh--grocery, dairy, produce, tobacco…all of it. Shit, eighteen months ago if

that bill was less than twelve thousand I would’ve thought we were having a

slow week. But now? Hell, we’ll be lucky to sell half this stuff.”

Hugh backed away without looking at the

sheets. “You don’t have to show me, I set the prices, remember?”

“Then you of all people should know why I

had to cut your hours in half.”

He knew Bob was right, he’d seen it coming

for a long time. Hugh hated himself for it, but he pressed on anyway. “You can’t

do this to me. We’ve been friends for too long.”

“Please don’t. No more of this ‘friends since

elementary’ crap. We’re in our forties now. You could’ve moved on, found

something better years ago.”

Bob’s tone was soft, but the words hurt

Hugh more than the cut hours. He shut his eyes and steadied himself back against

the desk for a few more moments. What had the warning been he’d just seen in

his mind? All he could see now was the worried look on his wife’s face, the

disappointment. Again.

“How’s Cathy’s ankle?” Bob asked, as if he

could read Hugh’s mind.

“It’s healed up fine, but she hasn’t gone back

to work.”

“Well, maybe now…”

“Yeah,” Hugh finished for him. “She’s not

going to have much of a choice.”

Bob stood up and hesitated awkwardly for a

second. He was about to offer a hand out, but settled to put them both in his

pockets instead. “I’m sorry, Hugh. Really, I am.”

“Monday? Do I come in on Monday?”

“I have Mondays covered, but Tuesday just

like normal. And the other days, well, we’ll settle that up next week.”

“Every weekend a long weekend now, hey?” It

was a feeble attempt at humor, but it was a good opportunity to get the hell

out of his office. “See you Tuesday.”

Hugh strode through the warehouse in a

daze. Someone said goodnight but he was too mentally shell-shocked to see or

care who it was. He paused at the file maintenance office door, his office for

the last nineteen years. The sound of the compressor room right next to it had

been a constant reminder of how unimportant his position was. The thunderous

whir of fans and cooling machinery shook the little windowless space where he

was paid twelve dollars an hour. He’d started at nine.

The freight unloading door to the left side

of his office began to rumble open. Cold air rushed in around his ankles with a

swirl of powdery snow. Hugh nodded to the teenager waiting with the delivery

van outside without looking him in the eye.

“Winter is finally here, Hugh,” the kid

said as he began to load groceries into the back seat.

Mr. Nance, you little shit.

He zipped his coat up and shuddered. The

kid (

Tommy Jacobson? Timmy?

) though disrespectful, knew how to call the

weather. The clouds above were low and grey, rolling in quickly from the

northwest. An inch of the white stuff had fallen throughout the afternoon, but

the heavy wet crap was just moving in. The temperature had dropped at least ten

degrees since morning, and whatever fell during the night would be staying for

months. Winter in Manitoba was definitely here.

Hugh jogged over to the staff parking lot

and jumped into his car. He slammed the door and watched dust settle onto the console

from the cracked upholstery above his head. He glared back at

Little City Food

Store

and after a moment’s consideration gave it the finger. It was the

best he could do. He thought of his wife again and groaned. How was he going to

break the news to her? He pictured the look of shock on her face, then the

disappointment, and then the bitterness.

Why

hadn’t

she gone back to work

yet? She was a fucking hairdresser. They hadn’t made a lot of money in their

lives, but combined, they’d managed to support their family.

“Ungrateful bitch,” he muttered into the

steering wheel. He felt bad as soon as he said it. What kind of man talks like

that about the woman he’s supposed to love? What kind of man works at a dead

end job for almost half his life?

He looked into the rear view mirror.

Balding on top and going grey quickly at the sides. His pale blue eyes were

bloodshot and the lower half of his face was covered with stubble. He hadn’t

bothered to shave that morning.

Why bother?

He dug into his coat pocket and pulled out

a pack of cigarettes. He lit one and started the car. He undid the window an

inch and exhaled smoke out as he wheeled down the back lane. Only four smokes

left, not enough to get him through the night, not enough money in his pockets

to buy more. If ever there was a night he needed to chain smoke, this was it.

Cathy was always harping for him to quit, it was a filthy habit. Their kids

shouldn’t have to inhale his second-hand poison. They didn’t have to, he

thought. He’d been forced to smoke outside the house for the last fifteen

years. He wouldn’t be forced to quit by anyone. It would be his choice.

I’ll quit when I’m good and goddamned

ready.

There wasn’t enough money for cigarettes,

but there was enough loose change in his pockets for a couple of lottery tickets.

Two bucks turned into a few million could improve their lives substantially. He

took another heavy drag and turned onto Main Street, thinking of his old

friend, Bob Richards once again. Not a great friend, more of a constant

companion of his growing up. A reminder of how badly Hugh himself had done in

life. Bob had always been smarter, better looking, and far more outgoing. He

had a different girlfriend for every month of their senior high school years.

Hugh had one, and he ended up marrying her.

Don’t blame Bob for your situation, the

little voice in the back of his brain said. And don’t make it sound like such a

burden being married to Cathy; she’s a great gal, it added. The little voice

was getting weaker each day.

He parked the car in front of Reynolds

Liquor Mart and stepped back out into the wind. The first sleety flakes began

to pelt into his face. He’d have to pick up the tickets quickly before the

roads turned ugly. He crushed the butt of his spent cigarette into the ground

and walked toward the entrance, pulling the coat collar tightly around his

neck.

The door swung out from the inside and

smacked him on his lowered forehead.

“Oh, Hugh! I’m so sorry,” a female voice

said. She reached for his elbow; he pulled it away and rubbed his head. He had to

bite his tongue before his favorite expression spilled out.

For fuck’s sake

was what he wanted to say, but when he looked up and saw the concerned, pretty

face, he was grateful he’d kept his mouth shut.

“Not your fault Suzey, I should’ve been

watching where I was going.” Hugh had a little fling with Suzey Wilkinson a

year after he was married. It had only happened once, a

big

mistake. She’d

come out of a disastrous short marriage resulting in twins, and the night they

spent together was brought on by his own greedy desire. Marrying young and

partying hard in small towns was a bad mix. Cathy had deserved better. He

looked at Suzey and smiled.

Damn, she’s still pretty. Must be

pushing fifty.

The two hadn’t spoken of it since, and he

wondered sometimes if she even remembered. She was happily remarried and had

four more children. The twins had already graduated and moved on. Hugh still

felt a little awkward whenever he ran into her. Did she ever think about him?

He doubted it.

“If you’re buying tickets, don’t bother. I

have the winner right here,” she said with a laugh, waving a slip of paper in

front of him.

“Huh?”

“The lottery…it’s worth over forty million

tonight.”

“Right, the lottery,” Hugh finally

answered. He wiped away the sleet that was building up on his shoulders.

Suzey opened the door wider so he could

step inside. “How’s work going, Hugh?”

“It’s going,” he replied with a weak smile,

wanting to get off the subject. “You don’t mind a little lotto competition do

you?”

“No problem, just don’t pick the same

numbers I did. I don’t feel like sharing.”

“Take care, Suzey,” he said and watched her

walk out into the cold. He loved his wife. Well love is what he called it, but

he couldn’t help but think from time to time how it would’ve been if more had

developed from that one night with Suzey so long ago.

Hugh passed by the beer section on his way

to the front of the store and contemplated getting good and drunk. He had half

a bottle of rum left over from last Christmas. Tonight might be the night to

finish it off.

Gary Reynolds said hello without looking up

from his newspaper behind the counter.

“Give me three bucks in quick picks,” Hugh

said, digging through his pocket for the money.

The bald-headed liquor mart owner punched

in the sale on the lottery terminal and handed Hugh his ticket. “Looks like she’s

settling in for a good blast out there,” he muttered with disinterest.

“At least the farmers have the crops off,”

Hugh said. He hated small talk, especially small talk about weather and

farming.

Farmers have had their crops off for

weeks. He must think I’m a real idiot now.

Gary pushed the thick rimmed glasses up the

bridge of his bulbous nose and studied his customer with more attention. His

narrow, watery eyes made Hugh uneasy. The old bastard was probably drunk, or

stoned, or both. “What’s the most you ever won playin’ this game, Hugh?”

“I don’t know.” Hugh thought about it for a

few seconds. “I got sixty or seventy bucks on four numbers once a few years

back.”

Gary grinned, revealing more gum than

teeth. His thin moustache curled up above his thick upper lip. “Did it change

your life any? I mean, you been buying tickets faithfully now for more than a

dozen years or so, once, sometimes twice a week.”

“What’s your point, Gary?” He was done

being polite. The time for small talk had passed. “I’m supporting your

business, aren’t I?”

“No money in the lottery for me,” Gary

answered. “If you wanted to help support me, you might buy a bottle of booze

once in a while. All I’m saying is your money is probably best spent on

something else besides the long shot of winning a few million bucks.”

“Forty million bucks.” He looked behind

Gary and pointed to the pictures pasted on the wall. There were over two dozen

stupid, grinning faces holding oversized cheques for various big dollar

amounts. None of those winners had purchased their tickets at Reynolds Liquor

Mart, but it was good advertising. “Somebody has to win.”

“Yeah, I suppose so.” Gary went back to his

sports section. “You can’t win if you don’t play.”

Hugh was about to leave when he saw a

lottery newsletter near the scratch and win terminal. He picked one up and saw

more black and white pictures of recent winners on the front page. Some were

old, some were young, and they all had that same mindless expression pasted on

their faces, those big shit-eating grins.

Is that what bliss looks like? Would I

smile like that for the camera if I won forty million dollars?

He flipped the paper over and saw the

winning numbers listed in order from the beginning of January until the end of

October. Most had been won, but a few had carried over. Any one of those random

sets of six numbers could have changed his life already. Where would he be now

if he had?

Some place warm where there was sand

instead of snow.

Maybe there was some kind of formula to it.

He focused in on the different months; the neat little columns looked all the

same. The numbers three, eleven, and twenty-nine seemed to be everywhere. He

looked a bit closer. So did four, twelve, and thirty. And thirty-one, and thirty-two,

and thirty-three.