Live Long, Die Short (7 page)

Read Live Long, Die Short Online

Authors: Roger Landry

Basically, we act like, and therefore believe, that older adults are a societal responsibility; productive years are behind them; they are in a recreation or entitlement mode; they are cranky and demanding. Nowhere is our low value of older adults more evident than in the media. At a minimum, television and movies portray older adults in a manner that does not evoke respect. At its worst, older adults are the object of mocking humor and condescending pity. Perhaps this attitude stems from a utilitarian view of people as workers that began with the Industrial Revolution and has carried over into the digital age, or from the related phenomenon of older adults turning their back on salaried employment as soon as possible and adopting a recreational “fully retired” lifestyle. Or perhaps it’s just an accurate depiction of the result of our marginalizing public policies. In any case, it will come as a surprise to many that this less-than-flattering view of older adults is a new phenomenon.

Dychtwald reminds us in his book

Age Power

: “For most of history, in fact, it was maturity that was prized. Until relatively recently, the old, more than any other group, controlled power, assumed leadership, and set the example for others. In the early centuries of American history, in nearly every aspect of community, family, and work life, old people reigned. Only during the twentieth century have they temporarily been knocked to the mat, viewed largely as a social burden.

15

Dr. Dychtwald also believes that this situation will shift, and that belief is the basis for his prediction of “profound changes” made in

Age Wave

.

We will return to predictions later, but first, let’s discuss the basis for these predictions.

Death is not the greatest loss in life. The greatest loss is what dies inside us while we live.

—NORMAN COUSINS

T

he cat’s out of the bag and there’s no going back. Your grandmother’s belief that how she aged was primarily determined by genes and a little bit of luck, well, that belief has gone the way of the eight-track player. The fact is, we can no longer blame our parents for our aging experience. In 1984, the MacArthur Foundation assembled the Research Network on Successful Aging and began what was to be a seminal study on aging. Jonas Salk, the foundation’s most famous board member, had challenged them to study the successes and not the negative aspects of aging. Their findings changed our understanding of aging forever, jolting us from our Dark Age attitude into a revolutionary new perspective of this common human experience.

Th is historic study clearly proved that

how we age is mostly up to us,

and it rocked our stereotypes of aging to the core, challenging us as a society to rethink long-standing assumptions; forcing us to reevaluate approaches to healthcare, senior living, retirement, education, and even recreation. It also threw down a gauntlet, a moral imperative, to rid ourselves of what Dr. Robert Butler labeled “ageism” in his 1975 book,

Why Survive?: Being Old in America.

1

Ageism is age discrimination, which commonly fosters a

stereotype or notion of aging as mostly about decline. With the MacArthur Study findings, such a notion was now no longer tenable.

The MacArthur Study findings were clear: 70 percent of the physical difference and 50 percent of the intellectual difference between those who age in the usual way and those who age more successfully were due to lifestyle, the choices we make every day.

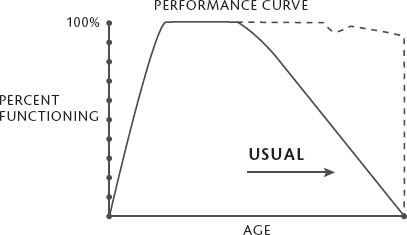

So, we ask, what does all this mean? If I age successfully, just what does that look like? What happens if I don’t live this lifestyle the MacArthur Study described? Do I age unsuccessfully? Drs. Rowe and Kahn are very clear about this, and our aging curve helps us to understand their guidance. Aging in the “usual” way is pictured in figure 2 as the solid line: an aging experience in which we are born, grow to maturity, and then at some point, because most diseases that kill us now are chronic diseases (rather than the acute diseases that ended the lives of our ancestors), begin a period of decline. This decline can now dominate a larger and larger portion of our lifespan because we’ve learned how to manage—yet not cure—chronic diseases such as heart disease, lung disease, arthritis, diabetes, and even cancer. Successful aging, on the other hand, depicted as the dotted line, is associated with maintaining abilities for a longer time, declining more slowly, and remaining minimally impaired despite advancing age.

It is clear from this curve that since lifestyle choices are associated with a more successful aging experience, such choices influence not only the quality of our life but also the quality of our death. Since life expectancy has upper limits, the longer we can stay at high levels of function, the more likely that the “terminal event,” as we say in medicine, will be short. This is called

compression of morbidity

, and it is the key to dealing with the dramatic demographic shift we are experiencing worldwide. Dr. James Fries introduced this concept in a keynote address to the National Academy of Science’s Institute of Medicine in 1982.

2

Compression of morbidity essentially means that the time we are sick at the end of our life is short: Rather than living the later phase of our life according to the predictions of those who associate aging with decline (my friend and colleague Dr. Bill Thomas calls these people “declinists”), we can indeed choose another route, a higher road more under our control even at the road’s end. According to the MacArthur research, my autumn leaf analogy—in other words, dying short—is possible!

Consider the final chapter in two men’s lives. Andrew is eighty-five years old and on his deathbed. For the last year, he has been bedridden in a nursing home, too weak to sit up. Three years ago, he fell and broke his hip. After nearly six months in bed he was able to walk minimally with a walker. Ten years ago he had a stroke that paralyzed his right side and left him unable to speak. After a year of rehabilitation, he was able to walk and speak, but with difficulty. Fifteen years ago, he had a mild heart attack, caused, his doctors said, by his long-standing adult-onset diabetes, which had in turn been brought on by his obesity.

Harold, eighty-six years old, is tragically killed by a drunk driver while bicycling in Spain. The week before, he watched the running of the bulls in Pamplona, something he had wanted to see most of his life. He had been on a month-long trip with his wife and granddaughter through France, Portugal, and Morocco. He’d taken the vacation after finishing his third book on American history, a topic he had pursued avidly after his retirement from his accounting business.

Two stories. One of “usual” aging, in that it is a story of decline not unexpected in our society. The other of vitality and purpose right up to the last moments. One with almost two decades of impairment, dependence, and lower quality of life. The other with a very brief end. Both gone, but with a dramatic difference in the last phase of life. If you could pick between the two, it’s obvious which you would choose. And now we know we can. But do we?

OK. So, in a nutshell: We can live a longer, higher-quality life that ends in a short time (like fall foliage dropping off the tree) without the pain, expense, anxiety, and burden to our families. Do I have any takers?

Of course I do. Who wouldn’t want this? And luckily,

we

are the biggest factor in making this happen. Yet you wouldn’t think so when you look at the numbers. Despite the fact that we’re pretty much in the driver’s seat as to how we age, when you look at the major causes of death, they are chronic, slow-decline, “I’ve lost control of my life”–type conditions. There’s no dropping off the tree with most of them.

Here are, according to the Centers for Disease Control, the major causes of death in the United States in 2010:

- Heart disease: 597,689

- Cancer: 574,743

- Chronic lower respiratory diseases: 138,080

- Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases): 129,476

- Accidents (unintentional injuries): 120,859

- Alzheimer’s disease: 83,494

- Diabetes: 69,071

- Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis: 50,476

- Influenza and pneumonia: 50,097

- Intentional self-harm (suicide): 38,364

3

At least six, and some may argue all, of these causes of death are modifiable by lifestyle and life choices. We can avoid them, have them for a shorter period of our lives, or have them with less impairment. The MacArthur Study removed the veil of fatalism and impotency from these conditions. And here’s more good news from the MacArthur research:

It is never too late to make a difference

, to change the slope of our own aging curve. Even when life throws you one of its inevitable curveballs and you find yourself having lost some of your abilities, it is absolutely possible, and in fact necessary, that you respond in a deliberate way, with the knowledge of what it takes to prove the declinists wrong, and halt your slide by stabilizing what you do have, or regaining some, or all, of what you’ve lost. Lamenting your loss,

beating your breast over it, or accepting it as part of your inevitable decline is inviting a trip further down the slide.

We now have a picture of aging that is empowering, in that each of us has a major input in what kind of older adult we will be, how independent or dependent, how vital or impaired, whether we flourish and continue to grow, or whether we wither away. Yes, we are now age empowered.

But we’re also challenged. Now accountable for our own aging experience, we’re challenged to become aware of what it takes to age successfully and to incorporate this into our lives, because the MacArthur Study, in addition to showing us that more was possible, tells us that it’s never too late to make a difference, to grow, to maintain what function we have now, or, at the very least, to change the slope of our decline. Luckily, the study also tells us what it takes to travel what I call this “high road to aging,” to age more successfully.

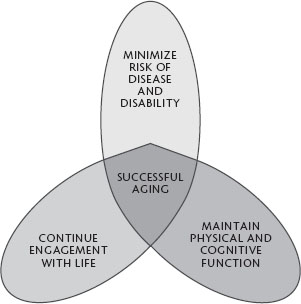

Those who age successfully have three characteristics in common—characteristics that, in fact, define the term

successful aging

—as illustrated in figure 3.

Those who age in a better way

maintain their physical and cognitive function

. Basically they

refuse to rust out

, challenging themselves physically and intellectually as a matter of lifestyle. Rather than buy into the stereotype of aging as decline, our successful agers believe that by using their faculties, whether physical or intellectual, they can at least maintain, and possibly expand, these abilities.

These aging gurus

minimize their risk of disease and disability

. They

refuse to be victims

, making great efforts to identify their risks for impairment, loss of independence, and even death and then doing all they can to

lower those risks

. Reading, researching, and working with their physicians, they become educated seekers of a lifestyle consistent with the MacArthur findings.