Read London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City Online

Authors: Drew D. Gray

London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City (11 page)

COPING WITH CHANGE: VICTORIAN VIEWS OF THE COUNTRYSIDE AND TOWN

The Victorians, perhaps more than any previous generation, were having to come to terms with the changing environment around them. The 1830s and 1840s had seen acceleration in the industrializing process that had begun in the previous century. While we should be cautious of depicting mid-nineteenth-century Britain as predominantly industrial (for it was far from that), the rate of change was arguably dramatic. A falling death rate ensured steady population growth despite a falling birth rate. In addition internal migrants flocked to the growing towns and cities from all over the United Kingdom, and they came to London in particular! Britain's population doubled between 1801 and 1851, from some 9 million souls to more than 18 million. While for most of the eighteenth century the rate of population growth had been 0.46 per cent, in the period to 1911 it averaged some 10 per cent.' According to a royal commission report of 1841 an `entirely new population [had] been produced' Where once `there was not a single hut of a shepherd, the lofty steam engine chimneys of a colliery now send their columns of smoke into the sky'4 In the period 1801 to 1911 the proportion of the British populace that lived in urban areas rose from 20 per cent to 80 per cent.'

The popular literature of the day reflected this change in the rural landscape; Merry & Wise published a short story called `Pits and Furnaces, or life in the Black Country' where three children comment upon the strange activities of a group of men in a field near their home. `Papa!' exclaimed Fanny, `what do you think they are going to do? I hope they will not spoil that green field: there are so few others near our house' Her father explains that they are looking for coal and this excites the imagination of Fanny's brothers who realize they can `watch them very easily, and shall see it all from the beginning, thus neatly juxtaposing the Victorians' competing attitudes towards progress and conservation.' The story unfolds as the boys explore the developing site, taking home samples for analysis and demonstrating the Victorians' love of science. Fanny, representing a female stereotype associated with continuity by way of contrast to the more dynamic aspect exhibited by her brothers, questions her mother about the origin of coal. She learns, as does the intended reader, that coal comes from the great forests that once covered the land before men (specifically English men) cultivated the soil. Yet all the efforts of ancient and `modern' men are placed within the context of religion in shaping human society. As Mrs Hope tells her daughter Fanny, `most wonderful of all that God should so arrange it that the decay and destruction of the plants of past ages should prove such a source of comfort and wealth to the present race of beings - thus linking us with times long gone by, and encouraging us to trust Him for the future'' Religion and science, those two contrasting and competing bastions of Victorian society, are thus neatly entwined in this story of progressive industrialization.

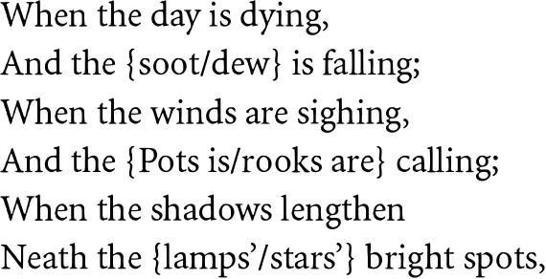

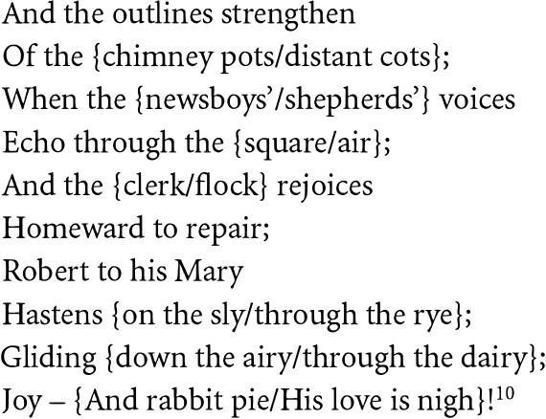

The contrasts between town and country appear in other popular publications of the day. In Jane Boswell Moore's `The Black Pony, Charlie and Phil go to live with their grandfather where, `instead of the dull streets they had become accustomed to' were `pleasant green fields, with high grass and corn' 8 Much later in the century the Rev R. F. Horton complained that there `are vast tracts of this green and pleasant land where the grass and flowers have ceased to grow, and the trees which survive are stunted and warped" That the Victorians were well aware of their somewhat ambiguous relationship with rural and urban living is demonstrated by this interactive poem published in 1874:

It has often been urged, and with some reason, that pastoral poetry must fail to be properly appreciated by dwellers in towns; while on the other hand ... urban verse must be unintelligible to the rustic. In the following poem we have striven to meet the requirements of both classes of readers.

Doggerel it may be but the emphasis is firmly placed on the differences between urban and rural life with a sense that the former is less pure, but perhaps more interesting. The manufactured nature of the urban environment and the naturalness of the rural reflect Cowper's idiom that `God made the country, man made the town' However, we should not read Cowper too simplistically: `If man made the town, then the town demonstrates both his state of original sin and his capacity for the greatest of human achievements'" Thus Cowper reflected the ambivalent position the countryside had in contemporary discourses, `sometimes seen as the abode of joy and tranquillity, more often regarded as dull'" Beatrix Potter had also highlighted the differences between urban and rural life in her Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse (1918). As P. J. Waller has noted, in Potter's tales the `town is mannered and alarming to Timmy [the country mouse], the country dull and dirty to Johnny' .13 Potter herself lived in London before later moving to the Lake District. The cities of England held a fascination for those that lived outside them, a fascination made all the more real by the rapid advance of the railways, which meant that almost anyone anywhere in Britain could experience urbanity for the cost of a few shillings.

The Victorian economy was built upon progressive and successful industrial growth in which knowledge and skills were crucial. Towns and cities were, by the mid-nineteenth century, well ahead of the countryside in this respect. The availability of labour (and importantly cheap labour), along with the clustering of workshops and suppliers with access to transport networks and the large numbers of available customers drove business growth in the urban environment. So it is perhaps odd that Victorians were so concerned with the growth of towns and the implications this had for their society. After all, it was extremely successful in terms of the wealth it created. Certainly many contemporaries were very positive about the city and Victorian urbanites were proud of their towns and built impressive architectural monuments to demonstrate this. We need only cast our gaze at the town halls, squares, statues and other buildings that survive from the Victorian era or at the wealth of guide books, engravings, paintings and maps that `celebrated and explored the towns' of Britain in the nineteenth century.14 We can tell what the Victorians felt about their urban environments when they festooned these buildings with words such as `progress', `growth' and `improvement' These were powerful expressions of urban pride.

In the early years of the nineteenth century new arrivals in the growing towns and cities felt little sense of neighbourhood, having exchanged the close-knit community of village life for the anonymity of urban living. However, as transport networks expanded and towns grew in size new identities were created and competition developed: village rivalries expanded into town and even regional competitiveness. This rivalry was fuelled by economics and trade, the growth of organized sports such as football and rugby and, after 1880, by the emphasis placed on civic pride by compulsory education." Thus, while England was becoming a predominantly urban culture as the last decades of the nineteenth century approached it retained its strong links to the countryside and to nature. Ruskin's gloomy vision of the future was coupled with his own obsession with all things medieval and both reflect the Victorian discomfort with industrialization and urbanization. 16

All of which brings us back to the concerns so often expressed at the time that the towns and cities of Britain were somehow detrimental to the health of the nation. Even today it might be fair to say that Britain has an anti-urban sentiment in its culture with our eulogizing of the countryside and our attempts to restrict urban sprawl even in the face of a massive housing shortage. We see ourselves as living in a 'green and pleasant land' despite the fact that most of us live and work in cities and towns and enjoy the benefits that they bring. Two modern institutions devoted to the preservation of our rural heritage had their origins in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. The Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) was established in 1926 and today calls for a closer engagement with a protected and sustainable countryside. The CPRE was preceded by the National Trust, which was founded in 1895 by three Victorian philanthropists: Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley, all of whom were concerned about industrialization and unchecked development and set up the trust to conserve Britain's countryside, coastline and buildings. The preservation or conservation of England has therefore been closely linked to notions of national identity for over a century. Today the city carries most of our fears about modern society and thus echoes with our Victorian past. For the middle classes of late Victorian London their particular concerns about the dangers of the city were focused on the East End, but this has historically been a difficult area to define and is as much subject to myth making as the Ripper himself.

DEFINING THE EAST END

Increasingly in the late nineteenth century the city was being identified as `a place of social danger: from the loss of customary human feelings to the building up of a massive, irrational, explosive force"' Nowhere was this more apparent than in the capital city, London. In London this danger was applied to the east of the metropolis to the area we have come to know as the East End. To some extent, like `Jack' himself the East End is a product of a complex meshing of perceptions and stereotypes and it becomes increasingly difficult to identify the `real' East End from that of myth and representation. According to Keating the East End was in many ways a creation of nineteenth-century writers, including novelists, reformers and journalists. `It was the creation of Edward Denison, Samuel Barnett, Charles Booth, Walter Besant, Arthur Morrison, and Jack the Ripper."' After 1880, according to the contemporary periodical Nineteenth Century, the negative association of the East End with poverty and crime was `rapidly taken up by the new halfpenny press, in the pulpit and the music hall' so that `it became a concentrated reminder to the public conscience that nothing to be found in the East End should be tolerated in a Christian country"' Since then we have had the additional overlay of the wartime `Blitz spirit' and the machinations of the residents of Albert Square in the BBC's long running soap opera, EastEnders.

For the mid-Victorians the East End was somewhere that only occasionally required their attention. When cholera broke out or when a particularly nasty murder case reached the papers, as it did in 1811 on Ratcliffe Highway, the Victorian middle class shivered in their comfortable homes and held their noses lest they be infected by the pollutant to the east. Indeed it is the smell of the East of London that is most redolent in much of nineteenth-century writing. Thus in visiting the East End in 1841 the future Lord Shaftesbury discovered such `scenes of filth, discomfort, disease! [such] scenes of moral and mental ill ... No pen or paint-brush could describe the thing as it is. One whiff of Cowyard, Blue-Anchor, or Baker's Court, outweighs ten pages of letter press'20 Much of the association of the East End with nauseous odours reflects the area's industry and poverty. As London developed, the dirty trades were often located in the East. Here were the slaughterhouses and tanneries, here too many of the homes of the poor - close by the docks where so many Londoners were employed. The area south of Whitechapel High Street was full of butchers and slaughterhouses throughout the nineteenth century. The Poor Law report of 1838 uncovered some of the problems of disease associated with the trade:

Dwellings thickly crowded with inhabitants stand all around the slaughter-houses [...] in the passages, courts, and alleys, on the very opposite side of the street from the houses of which there are no drains into the common sewer, fever of a fatal character has been exceedingly prevalent.21

The contrasts between West and East had a long history and were clearly a subject for amusement. In 1840 one periodical reported that in response to the laying out of a park in the East End the `butchers of Whitechapel have resolved to christen it Hide-park, in order not to be behind the West-end in gentility and fashion. Anybody, moreover, who has visited the region in which the slaughter houses are situated, will know that they may easily have a "Rotten-row" of their own' 22