London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City (34 page)

Read London's Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City Online

Authors: Drew D. Gray

This was also an area associated with crime and criminality as we have seen throughout this book. The figures in Table 7.1 show that prosecutions for theft and other forms of property crime accounted for just over a quarter of all hearings. As with assault, the number appearing in the police court charged with some form of theft is in no way an accurate record of the extent of pilfering that went on in the period. In her study of the London police courts Jennifer Davis argued that many employers (whether large or small businessmen) would have been reluctant to go to the law in many cases: `Sentiment might prevent some small employers from prosecuting those with whom they worked closely' and we should not discount the fact that those with larger workforces may well have shared similar emotions. Others may simply have not wanted to take the time out of their busy lives to attend court, especially if this meant closing business in order for other employees to testify. After all, employers had the ultimate sanction: they could simply dismiss the thief and refuse to provide them with a reference for future employment. This may well have served as a more severe punishment than anything the court could administer.38

Individuals were accused of stealing all sorts of property that reflect both their needs and opportunities for theft in this part of London. In many instances the magistrates remanded suspects brought in for a few days while evidence could be gathered or the owner of the property found. The examination and re-examination of suspects had been a feature of the summary courts of the eighteenth century and can in itself be viewed as a disciplinary function operated by the magistracy. Suspected thieves could be arrested and imprisoned for a few days or a week before being released with a caution.39 Minor criminals could be sent to prison for short periods as William Dover was in August 1887: having stolen £1 4s and 6d the 18 year old was sentenced to a month of hard labour. Robert Richards was offered a choice after he was found to have stolen a pewter pint pot from a local pub, either pay a £2 fine or go to gaol for 14 days: he paid the fine. John Farrington's offence was more serious as he had broken into a shop in Spitalfields and had stolen a camera lens valued at 15s; the magistrate ordered that he be fully committed for trial. This case made the pages of Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper which gave the victim's name as Henry Schwero, a music seller, of 1 Fieldgate Street.40 The London press routinely sent reporters to the police courts but given the number of cases heard it had to be something either exceptional or topical for the papers to report it. In March, George Carlton and Henry Cranfield, described as `rough-looking fellows', were convicted of assaulting and robbing a Chinese seaman on the West India Dock Road. The magistrate said it was `an abominable thing that poor inoffensive Chinese could not walk the streets without being assaulted and robbed'. He sentenced the pair to two months' imprisonment with hard labour.41 Not all property crime was as direct as some of those noted above, nor were all the culprits easily identified as members of a criminal class. Charles Lawrence was a veterinary surgeon who was well known in the East End. He pleaded guilty to embezzling money from a firm of iron merchants and, despite them intervening on his behalf, he was sentenced to six months in prison - the maximum sentence the court could

As we noted earlier the reporting of crime at the police courts can only offer a glimpse into the workings of the summary courts. Reporters would have been necessarily selective about the cases they chose to bring to the attention of their readers. The salacious, the topical and the unusual would have been the staple fare of the court reporter. In the Pall Mall Gazette the police and magistracy had, after the Trafalgar Square and Hyde Park debacles, an implacable critic, and at Thames it would seem that Mr Saunders JP was under scrutiny by the editors and reporters that observed goings on in his courtroom. The inconsistency of justice was highlighted in this report from late 1887: `Mr Saunders of Thames Police Court does not seem to improve in his notion of justice' it declared, before going on to note that the magistrate had fined one offender just 5s for running over a man's leg while `careering round a corner' in charge of a milk van but then sentenced Edward Buckley to 14 days' imprisonment for simply stealing a pane of glass `from a stall outside a shop, despite him making no attempt to escape. Finally the exasperation of the Gazette was complete when `a lad named Costin was charged with the theft of a German sausage. This dreadful offence was too much for Mr. Saunders who committed Costin for trial'.43 Many of those brought before the court were offered the alternative punishment of a fine or a short period of imprisonment. In some of the capital's other police courts, Marlborough Street for example, most defendants chose to pay the few shillings fine. At Thames, according to Robinson of The Graphic, most of those convicted preferred to take their chances inside and `work it off' to use a contemporary expression. `Money is always "tightish" Stepney way, he explained, and `every unfortunate cannot expect a little private benefit - a "friendly lead"; as it is called, a whip round of friends, relations, and acquaintances - to meet the expenses of the very unlucky day which has brought matters to so sorry a pass'

Robinson's detailed overview of the workings of the London police courts were published over three editions in 1887 and include some wonderful illustrations of the court. We see policemen giving evidence, defendants receiving advice from their solicitors (when they could afford them) and women weeping in the dock, as well as the interior of a Black Maria - the police vehicle that carried offenders to and from the courtroom in East Arbour Street. After offering some delightful vignettes from Bow Street in his second report The Graphic's correspondent concluded by noting that:

Police cases are not always amusing, however - there are dreary desert wastes, over which the whole staff has to plod, and it is `hard lines' on the student of human nature if he has dropped in when School-Board cases and Gas summons are being stolidly listened to by a sorely-affected stipendiary. Now and then in a School-Board case there is a glimmer of interest, but in a Gas dispute - despite the subject of discussion - there is not the spark of light and life. The reporters slip down from their seats, the clerk of the court yawns ominously, the policemen show signs of utter weariness, visitors, interested in coming cases, drop into fitful slumber. The magistrate sits patient and resigned, the gas collector produces a whole army of defaulters, who file in, one after the other, with the invariable plea that they have not burnt one-half of the quantity of gas charged for. These gentlemen [the Gas collectors] summoned to appear are the only beings in Court who betray the slightest amount of excitement over the details - the collector turns over his dropsical note-book and calls therefrom the number of thousands of feet of gas consumed, and the amount due to the company in consequence and the magistrate invariably agrees with him: `judgement with costs' and calls the next case. At length the collector's last dreary statement is heard and his soporific presence is removed.44

Fortunately for the cub reporter sent to cover proceedings in the police court the opportunity to attend the sittings at the higher court at the Old Bailey presumably followed from a successful initiation at the lower end of the criminal justice system. While the summary courts represent the arena in which most Londoners would have encountered the law and have made their complaints, the Old Bailey was where the most serious (and therefore more newsworthy) crimes were prosecuted and judged.

THE OLD BAILEY: LONDON'S CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT

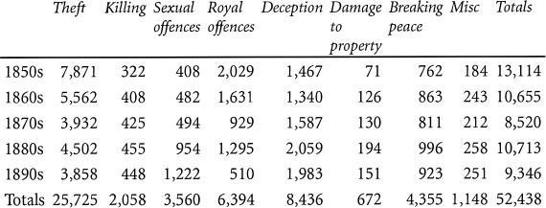

Between January 1850 and December 1899 London's Old Bailey courtroom heard over 52,000 trials for a wide variety of offences as Table 7.3 shows.

Table 7.3 Trials at the Old Bailey, 1850-1899

What is immediately apparent is the dominance of crimes against property in the statistics. Theft (which includes the sub category of `violent theft') accounts for 49 per cent of all crime tried at this level of the criminal justice system. If we included forgery and fraud (which come tinder `deception') and coining (dealt with under `Royal offences' as an attack on the currency was considered to be an attack on the monarch) then we can push this figure to 77 per cent. Interpersonal violence accounted for just 12 per cent and as we have seen a large amount of violence came before the summary courts. Trials for sexual offences, (rape, assault with intent to rape and bigamy) constituted around 7 per cent of the business of the court and a variety of miscellaneous offences (conspiracy, returning from transportation, performing an abortion, concealing a birth - to name but a few) made tip the remaining 2 per cent.45 We have already looked at murder in an earlier chapter and other forms of violence and sexual crime cannot be covered in any depth here. Therefore this chapter will concentrate on the key property crimes that concerned the late Victorians. If we take another look at the Old Bailey records it is possible to construct a more detailed table for analysing property crime over the second half of the nineteenth century.

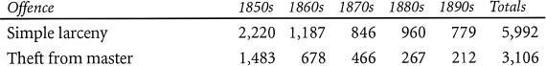

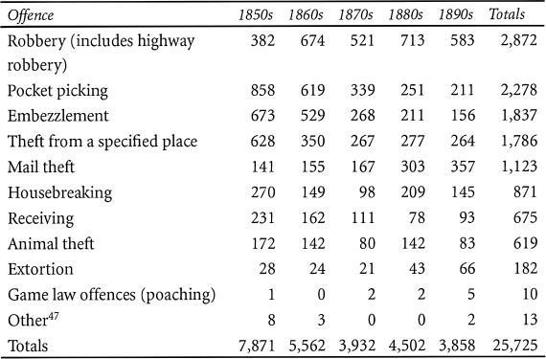

Table 7.4 Property offences at the Old Bailey, 1850-18994

Table 7.4 shows that there was quite a lot of variation in the prosecution of certain offences across the 50 years covered by this survey. How do we explain the peaks and troughs in crime statistics? This might reflect changes in legislation or in patterns of prosecution or indeed in perceptions of the seriousness of certain forms of lawbreaking. In general property crime was much higher in the 1850s than it was at the end of the period. This perceived fall in crime has in part been attributed to the gradual establishment and development of the Metropolitan Police from 1829 onwards. However, it also reflects moves towards using the magistrate courts to deal with a wider range of minor property crime. It was in the 1830s and 1840s that, as Clive Emsley has noted, a'flowering of the statistical movement' occurred in England and Wales, largely due to the work of Criminal Registrar Samuel Redgrave, who organized the way in which the statistics of crime were presented.48 This data was made available to the public and may to some extent have fuelled concerns about the amount of crime in society and the concomitant threat to private property and persons. Fluctuations may also have been the result of economic factors such as unemployment or agricultural depression. The 1880s, which saw an economic downturn after several decades of growth, has notably higher numbers of prosecutions at the Old Bailey than the decades either side.

As Table 7.4 demonstrates it was the offence of simple larceny for which most defendants were brought to trial in this period. After 1827, the distinction between `grand larceny' (the theft of goods to the value of one shilling - or 12 pence) and `petty larceny, was abolished. Simple larceny now covered all forms of theft that had no other aggravating factors that were prosecuted under more specific legislation (such as burglary, theft with violence or theft from a master for example). Burglary is the next highest subcategory which, if we include housebreaking, accounted for just under 20 per cent of offences prosecuted here. Stealing from one's master was clearly dealt with more severely in the earlier part of our period, the offence having been formally created in 1823 as a result of widespread concerns arising from the rapid industrialization of Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Masters had long been concerned with the depredatory habits of their domestic staff but this new law appears to have been aimed more at workers in the new industrial centres. Robbery generally meant theft from the person on the street either by single individuals or by groups of thieves. As we saw earlier the 1860s witnessed a'moral panic' about street robberies by gangs of garrotters who attacked their victims from behind.