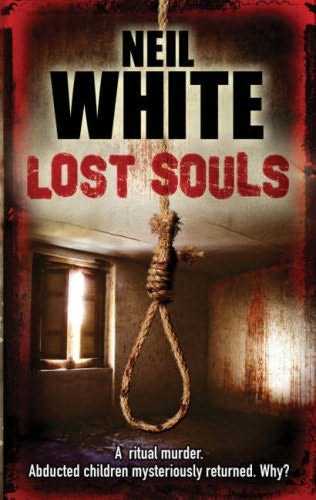

Lost Souls

NEIL WHITE

Lost Souls

To Alison

The old man turned away and closed his eyes, clamped his hands over his ears, but the images were still there, searing, sickening. He tried to shut them out, screwed up his eyes and started to pace. It was no good. He ended up where he started each time, next to her.

She was tied to a chair, her arms behind her back, her wrists strapped tightly to the thin spindles. Blood covered her face and painted her shirt in splatter patterns. He looked at his hands. They were sticky with her blood.

He closed his eyes again, but the sounds were harder to shut out. Wherever he paced, whenever he couldn’t see her, the noises were still there, like echoes, constant reminders.

He stopped to take some deep breaths. The woman he wanted to remember was the one he had known in life. She had been fun, vibrant, a face full of smiles. That was the image he wanted to keep, not the one in this room, her face a grotesque mask, nothing left of the person he’d known.

He couldn’t shake the image away. He had seen her

face in life; and now he had seen it in death. And it was worse than that, because he had seen her die, her eyes wide open, in pain, in fear, the knife getting closer. She had known what lay ahead of her.

He started to walk around the room faster, tears running down his face. He clenched and unclenched his fingers, looked up and then covered his ears as he walked, as he tried to stifle the sounds that once again crashed through his head. He had heard her last word, forced out through clenched teeth. It had come out as a guttural moan, but he had known what it was. It was

no.

She had tried to say

no.

He took a deep breath and stopped pacing. He turned to look at her. She was still the same. He put his head back and sobbed, and then he sank to his knees.

He stayed like that, rocking slightly as he sniffed back the last of his tears.

After a few minutes he stood up and slowly walked over to the chair. He put his hand on the woman’s cheek and gently stroked it, her skin soft under his fingers. But she felt cold. He leaned forward and kissed her on the top of her head.

‘I’m sorry, so very sorry,’ he whispered. ‘I tried to warn you. I really tried.’

The old man stepped away and looked down at his feet. He could feel the tears trickle down his cheeks, his skin parchment-thin, and as he touched them the blood washed away from his fingertips. He muttered a few words to himself, a private prayer, before reaching for the telephone.

‘Police please.’

He waited to be put through, and when he heard the voice at the other end of the line, he calmly said, ‘My name is Eric Randle, and I want to report a murder.’

North or south, murders are the same.

DC Laura McGanity blew into her frozen hands and, just for a moment, dreamt of London. Two weeks earlier it had been her home, but already that seemed like a lifetime ago. She had only moved to Lancashire, a mere two hundred miles from the capital, but it felt like a foreign country as the frigid air blew in from the hills that surrounded the town. She paced along the yellow crime-scene tape and it snapped loudly as it blew in the early-morning wind. She shivered and wrapped her scarf tighter round herself.

It wasn’t just the weather that felt alien. It was the quietness. She was standing by an open-plan lawn in a neat suburban cul-de-sac, with the hills of the West Pennine Moors as a backdrop, painted silver as the rising sun caught the dew-coated grass, just the snap of the crime-scene tape to break her concentration. She missed the London lights, the buzz, even the noise. In comparison, Blackley was like a constant hush.

Laura had been brought up in the south and trained by the Met, but love had brought her north. She

had arrived in a small town, concrete and graffiti replaced by moorland grasses and dry-stone walls. She knew she couldn’t afford a mistake. Her transfer north had been a risk, and she didn’t want to destroy her new career so soon. She had seen the looks in the eyes of the other officers in the station. Wariness. Suspicion. She was the girl from the big city, come to tell them their jobs.

She had to be alert now, because there was no time for distraction. With any murder the first twenty-four hours were the most important. After that, evidence on the killer could be lost. Fingernails got scrubbed, hair got cut, cars got burnt out.

She looked up just as Pete Dawson, the other detective at the scene, approached her. He was holding two steaming mugs of coffee.

‘You look like you need one of these,’ he said.

It seemed to Laura like he barked the words at her, the staccato speech patterns all new, the vowel sounds short and blunt. The London rhythm she was used to had more swagger, more bounce.

She smiled her thanks, and as she wrapped her hands around the mug she asked, ‘Where did you get them?’

He nodded over towards a house on the other side of the road, where Laura could just make out fingers on the edge of the net curtain, the light inside switched off so no one could tell that anyone was watching. ‘She’s been twitching those for half an hour now. I think she’s hoping for an update if she gives us drinks.’

‘Did you tell her anything?’

Pete shook his head. ‘I’m holding out for a fry-up. But be careful. These old mill girls can lip-read.’ When

Laura looked at him, confused, he added, ‘So they could still talk over the noise of the machines.’

Laura smiled. She liked Pete. He was one of those necessary cops. Precise minds are great—those who can dissect complex frauds or see leads in cases that look like dead-ends—but sometimes you just need someone to kick down a door, or find a quick way to prise information out of someone. Laura reckoned Pete knew many quick ways. He looked one wrong word from hurting someone, all crew-cut, scowl and scruffy denims. He was normally with the drugs squad, more used to throwing dealers against walls than loitering around murder scenes.

She took a sip of the coffee and sighed. It was hot and strong, and she raised it in thanks to the parted curtains on the other side of the street.

‘You look like you expected more,’ Dawson said, nodding towards the crime-scene tape. ‘Not used to the quiet life yet?’

A week before, Laura might have thought he was having a dig, but she knew him better now. Pete’s smile softened his words and his eyes changed. They became brighter, warmer, and she sensed mischief in them.

But he was right, Laura

had

expected more activity, the usual commotion of lawns being combed by uniformed officers, or a squad of detectives knocking on doors. Today there was none of that. The body had been taken away, but the first two cops on the scene were still there, an ashen-faced probationer and a police officer not far off retirement. Scenes of Crime officers were inside, their white paper suits visible through the

front window, but out in the street Laura felt like she was on sentry duty.

‘It doesn’t seem like the quiet life,’ she replied. ‘I moved north for a better life, and I get this,’ she nodded towards the house, ‘and in the middle of the abductions. It seems pretty dangerous around here.’

Pete shrugged. ‘It’s not always like this. Once we catch the bastard who has been taking those kids all summer, we’ll get more people to work cases like this.’

Laura looked back towards the house. ‘And are we any nearer to catching him?’

‘Every time there’s another one, we’re waiting for the mistake, the breakthrough.’ He shook his head. ‘He hasn’t made one yet.’

The abductions had been the big story in Blackley over the summer. The first one only rippled the nationals—everyone thought it was a runaway—but the next one confirmed a pattern and the media all came to town.

Children had been going missing all summer, snatched in the street. They disappeared for a week, sometimes longer. When they were found, they seemed unharmed, but there were things the eyes couldn’t see.

There had been seven of them so far, all boys: latchkey kids, early teens, cocky and street-sure. But that was a mask, protection from what they missed at home: love, security, attention. They came back with the mask slipped, and they seemed confused, frightened, days lost with no idea about where they’d been or what had happened to them. They’d thought they owned the streets, but now they realised how vulnerable they were, and that the world could be much crueller than they’d imagined.

They were found stumbling around, confused, lost, like they had just woken up. They were clothed, with no marks or injuries. They had to be examined intimately, just to check for a sexual motive, but there’d been nothing so far. They were sent home, back to the arms of their parents. The boys were all hugged a lot closer after that.

The eighth child was out there now, Connor Crabtree, with whoever was taking Blackley’s children. He had last been seen cadging cigarettes in a small car park behind a corner shop, accosting strangers as they went to buy milk or something. That had been six days ago, and no one had seen or heard of him since. The press were on standby, waiting for the inevitable return, something to report; the nation was gripped by the story. The press had even given the kidnapper a name: the Summer Snatcher.

Laura didn’t like the name—it sounded corny, no imagination—but she knew that it helped to keep the story in the news. It was more than just a story in Blackley, though. Everyone knew there would be more. Most parents had stopped their children going out, and the streets seemed quieter once it went dark. But the children being taken were the ones of parents who hadn’t listened, whose lives were too difficult to make room for their children.

There weren’t many clues. There were fibres on the boys, just tiny strands of cloth, from a blanket or something similar, but until they got the source they couldn’t get the match. The first two children had dust on their clothes when they were found, small specks of concrete

and traces of asbestos, but nothing specific. The police in Blackley were following leads, just to be visible, but everyone knew they were waiting for the return of Connor Crabtree, hoping it would bring fresh evidence.

Laura shuddered as she thought about her own son, Bobby. Four years old, in a strange town and a long way from his real father. She blinked, felt her eyes itch, took a deep breath. It wasn’t meant to have turned out like this, but Bobby’s father had decided a long time ago that Laura wasn’t going to be the last woman he slept with. He’d left, and Laura had struggled on her own for a while, but when she had fallen in love again she was able to give Bobby a family life once more. But it was hard. She needed to be with Bobby in the mornings. She missed seeing his sleepy face, and she wanted to know that he needed her.

‘What’s your theory about the abductions?’ Laura asked.

Pete considered for a moment, his face thoughtful, his hands jammed into his pockets. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘Could be a woman. You know, the kids are looked after and then given up again, some nurturing instinct satisfied.’ He smiled. ‘Not that they’d ever ask me anyway.’

‘Why not?’

‘I’ve spoken my mind too often.’

‘What do you think about this?’ she asked, nodding towards the murder scene.

He exhaled. ‘I don’t know. Some nutcase is the obvious guess, but there is one thing.’

‘Go on.’

‘The victim knew the killer. There was no break-in,

no sign of a struggle anywhere else in the house. No one reported it until the old guy made the call.’

Laura knew there was some sense in what Pete said. This was no domestic or a burglary gone wrong. It was a sadistic execution. A young woman, Jess Goldie, small and frail, barely twenty-five years old, had been strapped to a chair and strangled with a cord. There were no signs of a fight, no evidence of sexual assault. There was just a chair in the middle of the room, a dining-room chair with strong wooden legs, and she was strapped into it, her wrists tightly bound with thin nylon rope.

But that wasn’t what had struck Laura when she first went into the house. It was something else, the sight that had caused the young probationary officer to spend the next hour sitting outside, gulping lungfuls of fresh air in between dry-heaving.

Whoever had killed this young woman had ripped out her tongue and gouged out her eyes.

Laura had methodically examined the scene. She was at work, a detective, so the shock stayed away, her mind too busy to process emotion. It would come to her later, she knew that, maybe when she was in bed or taking a bath, alone and vulnerable.

There was nothing to suggest a struggle, no defensive wounds to the hands, no ripped clothing. But then Laura spotted the marks ringed around the woman’s neck, as if the cord had been pulled many times over. It hadn’t been a quick kill. It had been dragged out, made to last.

She turned to Pete. ‘What did you make of the old boy who called it in?’

Pete stroked his cheeks thoughtfully. ‘Eric Randle? Hard to say. He didn’t look the sort, if there is such a thing, and the only blood on him looked like contact blood. No splashes or spray. But it’s all too neat for me.’

Laura was about to ask something else when she heard a car drive into the cul-de-sac. It pulled up in front of the house, and she watched as a small man in a sharp suit climbed out.

‘Oh great,’ Pete muttered. ‘Now it’s all going to turn to shit. Egan’s here.’

‘Egan?’

‘DI Egan,’ said Pete, his voice low and quiet. ‘Dermot Egan. We call him Dermot Ego. You’ll soon find out why.’

As she watched the figure walk towards the house, Laura sensed that he was right.