Louis S. Warren (27 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

According to Cody, the role of Wild Bill Hickok became a prominent one for professional actors, too, sometimes in unconventional ways. Where scouts represented themselves on the stage and off, professional actorsâor confidence menâsometimes took to representing themselves as scouts, both on the stage and off. Thus, Cody relates that after Wild Bill Hickok's brief tour with his company in 1873â74, a rival stage company hired an actor to play the role of Hickok onstage, and to impersonate the gunfighter in public venues such as restaurants, saloons, and on the street. In Cody's account, the last stage appearance of the real Wild Bill Hickok was when he leapt onto the boards and thrashed this impostor in front of a packed house, just before returning to the West.

62

Whether or not Cody's Hickok tale was apocryphal, it captures the heightened tension between fakery and reality that energized frontier melodrama to its core. Before frontier melodrama emerged as its own subgenre, the standard melodrama's devotion to disguises and masks, with villains, heroes, and long-lost children continually donning new faces and new identities, was central to its appeal for audiences consumed with the artistry of imitation. The obvious impostures provided dramatic irony, allowing the audience insight into the action that the characters did not have, resolving it when the masks came off at drama's end.

63

The story of Hickok in the theater, punching the daylights out of somebody mimicking him, suggests how much the stars of frontier melodrama not only parodied all drama but also performed parodies within parodies. At times, the scouts in the dramas were so similar as to be almost interchangeable, and the genre threatened to swallow the “authentic” men who succeeded in it. There were two Jacks, “Texas Jack” and John “Captain Jack” Crawford (the latter emerged quickly on Omohundro's coattails in the mid-1870s). To the consternation of both men, audiences and seasoned show troupers alike often confused them.

64

Paradoxically, this was an appeal of the frontier or “border” drama. As the number of “real” scouts in “true” border dramas multiplied, myriad variations on the theme of authenticity and fakery permeated the action, making the typical masks and clumsy disguises of ordinary melodrama seem tame by comparison.

Buffalo Bill endured longest in the genre, and came to stand as its most “authentic” product. For this reason, scouts and actors who sought bona fides as frontiersmen attached themselves in one way or another to him. But in fact, he developed his own character by borrowing freely from others, particularly Hickok. For two years, in 1875 and '76, Cody played the lead in a play originally written for the lawman,

Wild Bill, or Life on the Border.

Because so many people confused Cody and Hickok anyway, few members of the audience probably realized that he wasn't the play's title character. But even if they were ignorant of Buffalo Bill's imitation of Wild Bill, the play contains dizzying twists on the theme of reality and fakery that pervaded the frontier melodramatic genre. The action swirls around counterfeiters who disguise themselves as Indians. Thus, the real scout plays a scout, opposite actors who play villains who fake Indians who fake money.

65

The denouement of the play resolves the many tensions between the fake and the real in favor of the latter. The character of Bill Cody apprehends the malingerers, and rescues George Reynoldsâthe father of Cody's love interest, Emma Reynoldsâwho has been kidnapped by the counterfeiters. In the end, the counterfeit ceases: the white men no longer play Indians, and they no longer make false money. The true scout, Buffalo Bill, whose fidelity is reinforced by the fact that he is “playing” himself, finds “true” love with virtuous Emma, the “true woman.”

Not all of the mimicry attached to the scout business was playful. On occasion, it veered into fraud, which posed real dangers for the leading lights of the scout business. For the game of authentic-and-copy to work, for audiences to enjoy the artistry of imitation, somebody had to be “the real thing,” that standard of reality against which the imitation could be judged. Cody's prospects hinged on retaining his status as the “real” Buffalo Bill. Should he lose his grip on that role, there was no other for him. He was not a professional actor.

In this sense, offstage impersonators posed a threat, something Hickok appears to have understood in his violent reaction to his impostor, and something Cody and Omohundro had to confront as well. After their first season together, Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack began carrying endorsements from military officers and western acquaintances, something that they each continued to do throughout their stage careers, because fraudulent theatrical companies, featuring actors claiming to be them, often traveled ahead of their own troupes.

66

In other cases, actors who played scouts in productions featuring real scouts like Cody and Omohundro would branch out on their own, trying to sell themselves as authentic frontiersmen. When Texas Jack took a break from the Buffalo Bill Combination in 1874, Cody temporarily replaced him with an actor. His identity remains a mystery, but he appeared asâand claimed to beâKit Carson, Jr. Mustered out of the company on Omohundro's return in 1875, he formed his own stage company and set out to make a name for himself in the scout business.

67

The efforts of Kit Carson, Jr., were in vain. His combination failed.

68

But he infuriated Cody, a fact that suggests how serious a matter imitation and impersonation could become for the stars of frontier melodrama. The business was fiercely competitive, with so many scouts qua actors and actors qua scouts that enduring as the chief draw required constant attention not only to stage production, but to authentic frontier exploits as well. Cody's entire stage career depended on his remaining the figure that other figures were imitating, even if much of his stage persona was a skillful imitation of other scouts, like Wild Bill Hickok, and, possibly, of other actors as well. We may assume that it was for this reason that Cody, who regularly made more in a week at the theater than he took home in a whole season of scouting, returned to the West to scout for the army in 1874, on the Big Horn expedition, and again in 1876, as the Great Sioux War burst upon the northern Plains.

69

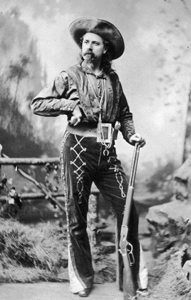

Cody in the stage outfit of black velvet and silver

trim in which he killed Yellow Hair (whose name

was mistranslated as Yellow Hand). Cody's the atricalism in Indian war had everything to do with the

competitiveness of frontier melodrama. Courtesy

Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

His careful attention to theatrical trappings in the scalping of Yellow Hair had everything to do with the endless one-upmanship of the scout business. Indeed, Cody's attention to theatrical effect in the killing (his costume, his shout “

First

scalp for Custer!

”) and his realism in staging it (same costume, same shoutâand the real scalp, too) entangled event and performance so thoroughly that historians and Cody partisans would debate for decades whether the killing was real or somehow faked. The movement of the encounter from battlefield to stage was so smooth that at least one man swore the enmity between Cody and Yellow Hair actually began in the theater. In 1936, longtime Rochester resident Robert Hicks told historian A. E. Sheldon that Cody had hired Yellow Hair for his stage combination in 1874, but one night Buffalo Bill flattened him with a roundhouse when the Cheyenne drank too much and began insulting ladies backstage. At that moment, claimed the alleged eyewitness, Yellow Hair swore vengeance, and the feud culminated two years later, at Warbonnet Creek.

70

In fact, Cody knew the frustrations of Indian fighting well enough to know, the moment he heard that Custer had fallen, that the Indian wars finally had a genuine battlefield martyr, a figure who would stand for the U.S. Army's conquest of the Plains the way Stonewall Jackson had stood for the Confederate cause in the Civil War. By becoming Custer's authentic avenger, shedding symbolic first blood and returning with the scalp to the eastern stage, Cody could claim to be the embodiment of the frontier hero, the white Indian who ventures over the line between civilization and savagery to vanquish evil by adapting savage methods, and then ventures back, without ever compromising his innate nobility.

71

But timing was as important as symbolism. News of Custer's death hit the nation's newspapers on July 4. The Fifth Cavalry was in the field and did not hear till July 7. On July 18, Cody wrote to Louisa that he had taken Yellow Hair's scalp, and a few days later he sent the scalp, warbonnet, shield, and other trappings to Rochester, where they were displayed in the window of a friend's shop, with a large poster explaining that Buffalo Bill had killed and scalped Yellow Hair in revenge for Custer's death. On July 23, the

New

York Herald ran the story of the CodyâYellow Hair fight.

72

Buffalo Bill became not only Custer's avenger, but the

first

of those avengers. All others were imitations. Accept No Substitutes.

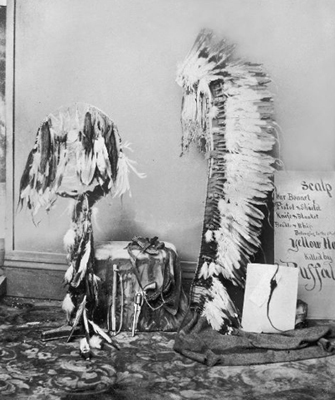

Yellow Hair's belongings, on display in a Rochester, New York, storefront.

Cody displayed them in the lobbies of theaters, too, but many condemned the

practice. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

In 1877, Cody's publicist, John Burke, noted privately, and in his typically cascading prose, that “Bill has had every advantage that could possibly assist a man, from the Sioux stirring up a stink, to poor Custer's misfortune, and Yellow Hand's [

sic

] unfortunate accident, with the hirsute incident, a âcustom more honored in the breach than in the observance' but very efficient in working up the âbauble reputation.' ”

73

Yellow Hair's scalp became Cody's trademark, distinguishing him in the scout business so effectively that other scouts' attempts to mark their own authenticity always seemed to mimic his. The futility of competing with Cody's brand of authenticity was perhaps most apparent to John “Captain Jack” Crawford, the self-styled “Poet Scout,” who starred briefly in Cody's combination in 1877â78 before going on to a lifelong rivalry with Buffalo Bill. Crawford was an Irish immigrant and Civil War veteran who emigrated from Pennsylvania to the Black Hills of Dakota Territory in 1874 (a move which may have been inspired by watching Cody's theatrical troupe perform in his hometown of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, in 1873).

74

Crawford became a correspondent for the Omaha

Bee

and an early settler at Custer City, Dakota Territory, where he set himself up as captain of his own company of volunteer scouts at the beginning of the Sioux War of 1876. Cody met up with Crawford during his scout forays that summer, and threw him an assist by recommending him to the military command as his own replacement when he left the Plains in August.

75

Cody's authenticity as scout and race hero was such that when the war against the Sioux continued in 1877, he did not bother to join. Crawford signed on as scout for the army again, and his military career culminated at the battle of Slim Buttes, where many of the Sioux who vanquished Custer were finally subdued. Crawford was reported to have killed and scalped a Sioux warrior during the battle. But, whether it was because of his own reticence about the deed or his inability to attach a name to his victim, or because it was too much a copy of Cody's “original” act of the year before, as a publicity device the scalp proved of limited use in his subsequent theatrical career.

76

In the fall of 1877, Crawford joined Cody's stage troupe, playing Yellow Hair in the reenactment of the fight on Warbonnet Creek. Seriously injured in a stage mishap, he soon decided to form his own theatrical company, letting it be known that he felt abandoned and manipulated by Buffalo Bill. Cody was angry and told Crawford that “had the accident not occurred I think you had [already] made up your mind to start out for yourself.” Cody's ire suggests how jealously he guarded his own authentic status, but it also hints at how difficult the scout business was. “People have flattered you until you think . . . that you are a great man. Jack, go ahead,” Cody urged. “You will find out that all that glitters is not gold.”

77

Nonetheless, Cody would not try to stop him. “I wish you success and I will never do a thing to hurt you.” The two men remained friends, but Crawford's jealousy at Cody's success made him bitter as old age approached. In bringing Buffalo Bill to stage stardom, he wrote on one occasion, “Ned Buntline created the most selfish and brutal fake hero ever perpetrated on the American people.”

78

Crawford's accusations notwithstanding, the fakery of Buffalo Bill paled beside the fakery of his many imitators, like Crawford, whose jealousy and mimicry of Cody only enhanced Buffalo Bill's claim to being “the real thing.”