Louis: The French Prince Who Invaded England (4 page)

Read Louis: The French Prince Who Invaded England Online

Authors: Catherine Hanley

17 Louis’s testament of 1225, in which he stipulates which of his lands will be left to which of his children.

18 The wide river Rhône at Avignon presented a formidable obstacle during the Albigensian crusade. The medieval bridge pictured (the Pont Saint-Bénézet) was built later in the thirteenth century to replace the one destroyed on the same site during Louis’s siege of the city in 1226.

19 A mounted and crowned Louis receives the submission of Avignon from its citizens at the end of the three-month siege.

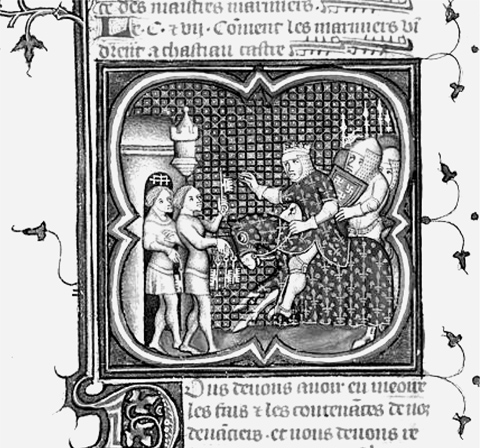

20 A composite image from the fifteenth century shows the events of 1226: the siege of Avignon (left), the death of Louis VIII at Montpensier (centre) and the crowning of Louis IX (right).

21 Following the exhumation of the royal tombs at St Denis in 1793, the archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir was able to make this sketch of Louis’s corpse before it was tossed into the ‘Capetian ditch’ along with many others. The body was still wrapped in the hide in which it had been transported to Paris.

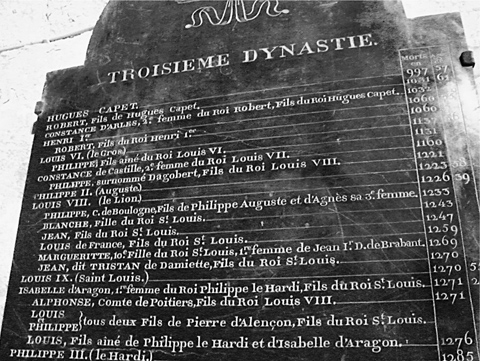

22 When the royal remains were re-interred following the restoration of the French monarchy they were all entombed together, with plaques erected to list the individuals. Here Louis’s name appears on a Capetian plaque, preceded by his father Philip Augustus and followed by his half-brother Philip Hurepel.

INTRODUCTION

I

N

A

UGUST 1216

Alexander II, King of Scots, rode south to offer his homage to the man he acknowledged as the new king of England; the official recognition of one monarch by another. The journey was a long one, and it took him and his sizeable entourage several weeks to travel all the way through the country; that he managed it in peace was testament to the authority of the man who held much of England in his grasp – a seasoned and respected warrior who was waiting for him at Dover. When Alexander arrived many of the most powerful lords of the realm were there to witness him kneel and give homage for the lands he held in England to the man he acknowledged had the right to bestow them.

The man in question was the son of the king of France, and his name was Louis.

* * *

Today, few people in Britain have heard of Louis. His name, so emblematic of France and of all things ‘foreign’, sounds odd in the context of English history. But if he had been more successful in his quest for the crown then we might now be as familiar with the name Louis as we are with others such as William and George which were just as foreign-sounding in their time. For, following in the footsteps of William the Conqueror, Louis sailed across the Channel to invade England and claim the throne. However, in contrast to his predecessor’s experience, there was for him no immediate and decisive battle, no swift coronation and no complete victory. Instead there was an almighty struggle punctuated by sieges and battles; there were vacillating barons who changed their allegiance from one side to another; there was devastation and suffering across the land as the war went on. Although he never succeeded in occupying the throne officially, Louis was in control of large parts of England from May 1216 until September 1217, and he was recognised as king not only by Alexander of Scotland but also by a large proportion of the great landholding barons. Indeed, it was these very barons who had invited him to invade.

It may seem incredible that England once reached a point where its lords sailed to the Continent and invited the son of the great French king Philip II Augustus to invade and take the throne, but this is exactly what happened: they made the offer, Louis sailed, landed unopposed in the south-east, marched to London and was proclaimed king by cheering throngs of people. He fought his way across much of the country and battled against the remaining adherents of King John and, later, of John’s son Henry. The story of how these events unfolded, and of how and why the barons decided that the most attractive candidate for the crown was a Frenchman, is a fascinating and under-explored one which we will investigate in these pages. Who was Louis, where did he come from, why was he invited to take the throne, what happened when he attempted to, what happened afterwards, what was his legacy, and why, crucially, do we not know more about him and about this pivotal era of English history?

Most of the narrative of this period centres on the English King John, with Louis a shadowy antagonistic figure in the background, but we will examine events from Louis’s point of view, exploring his life before, during and after the invasion; an invasion which we will investigate in some detail in the central section of the book. Louis himself will be the main focus of our attention, but we will also look at how he fits into the wider narrative of the relationship between kings and kingdoms at this time, and give some background detail to put his actions in context. Once our story of his life is complete we will discuss the question of why he is not called King Louis I of England, even though he held for some time as much or more authority than some of the monarchs who are officially recognised. We will conclude by exploring and analysing Louis’s profound and much under-appreciated influence on the course of English history.

In order to tell our story we need to draw on a wide range of evidence, and fortunately for us there are a number of contemporary sources available which can help us to reconstruct Louis’s life and his English campaign. Although he left no diaries or personal correspondence, numerous official documents from the period survive: charters, financial records, public letters, royal acts, papal bulls and so on. These sources form our factual base and are useful for confirming matters such as who, where and when, and also for identifying areas of agreement and disagreement, alliances and enmities. But they create only the skeleton of our story; in order to put flesh on the bones we must also turn to the more narrative sources of the period, the chronicles and texts written by contemporaries who were observing events as they happened or who had first-hand experience of them. Of course, these writers were not necessarily objective or even striving to be so: they are often biased and their narratives can be highly personal. But if we take this into account then we can safely use them to add colour and depth to our tale.

Let us, then, meet some of the men whose works we will consult. In this particular case they are all men: there were more women writers in the thirteenth century than is generally supposed, but those who wrote the chronicles and the great narratives of war were more likely to be monks in an abbey or clerics attached to an army, and therefore male. Our chroniclers hail from a variety of places – they are French, English, Welsh, Breton and Occitan – and they wrote either during Louis’s lifetime or shortly after his death. We will give a general introduction to them and an overview of their work here; further details on the texts, their languages of composition and their availability for consultation may be found in the Note on Sources at the end of this volume.

The best sources for Louis’s boyhood and youth are the two great chroniclers of his father Philip’s reign, Rigord and William the Breton. Rigord was a monk at the abbey of St Denis in Paris who spent many years compiling his

Deeds of Philip Augustus

; it is generally sober in tone, with Rigord realising he was writing for posterity and rarely offering a personal opinion. However, a gradual change in attitude can be discerned: the earlier part of the work portrays Philip in a very flattering light, but a few hints of criticism appear later on as the king acts in ways which do not meet with the Church’s approval. Rigord died in 1209 and so his chronicle of Philip’s reign is incomplete and it covers only the early part of Louis’s life.

William the Breton was also a cleric, but as he was a chaplain in the household of Philip Augustus he travelled around more than Rigord and is able to offer eyewitness accounts of some events, making him all the more valuable. He wrote two major works: another

Deeds of Philip Augustus

, which enlarged and expanded on Rigord’s work, and also an epic poem, the

Philippide

, which focuses mainly on the battle of Bouvines in 1214 and portrays Philip in the style of the heroes of antiquity. William’s work is useful to us and very readable, but we have to remember that he was among Philip’s greatest supporters, so anything he writes can be guaranteed to put Philip in the best light possible. This is sometimes to Louis’s benefit and sometimes to his detriment, as we shall see. Most of our references to William’s work will be to his

Deeds of Philip Augustus

; references to the

Philippide

will be noted as such.