Love in Infant Monkeys (12 page)

Read Love in Infant Monkeys Online

Authors: Lydia Millet

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author)

The upshot: Carter was no longer a liar, but still a clown. Comic-strip spoofs of the episode appeared, one of them starring “Paws,” a sharklike rabbit menace.

The president had been unmanned.

It was then that I had an inkling of what was going on. The killer rabbit had brought Carter to me.

“ . . . Never thought of you as the town bully myself,” he was saying. “You could be, ah, insistent, and you didn't always know your own strength, but heck, Robert, that's par for theâ”

“The killer rabbit,” I interrupted.

“Pardon me?”

“It's about the killer swamp rabbit,” I said. “Isn't it. Why you're here.”

Carter shook his head bemusedly, the vaguest hint of a smile playing about his lips. “Robert, I came to talk about

you

. And the wrong we boys did in letting you take the fall for us. In letting you alone be punished.”

you

. And the wrong we boys did in letting you take the fall for us. In letting you alone be punished.”

A diversion. It's hard for any guy to admit to his impotence.

Well, I kept at him. For a while, rather than face up to the lop-eared specter, Carter continued to claim interest in the incident that had led to my parents' leaving Plains. He showed a single-minded determination to divert the conversation from its true purpose. I could see how, in your high-level talks, he could have been a tiger. Still, I cycled back to the rabbit. And finally my subtle handling opened the floodgates.

“Oh, all right. Trivial episode, relatively, but I'll give you the story if you really want it.”

It wasn't till after the Reagan inauguration, he said, when he went back to South Georgia, that he really thought about the rabbit incident. He had time, in Reagan's early months, to read the jeering accounts; he had time to reflect that there had been nothing out of the ordinary in his behavior in the fishing boat. He had merely caught sight of an animal in the water and, surprised, jerked an oar in its direction. He'd done it the same way you might swat a fly. His train of thoughtâmoving from the Ayatollah Khomeini to Warren Christopher and standards of cancer care at Sloan-Ketteringâhad been rudely broken. He realized what the animal was a split second later and lost interest. He had seen swamp rabbits before, mostly in marshes; they took to water readily, to escape from predators.

Two of the four rabbit species in Georgia, he said, swam well; only the cottontails couldn't swim.

For a while, he said, he'd toyed with conspiracy theories. The Reagan strategists, after all, were lean and mean, unlike his own friendly posse of good ol' boys with their antiquated notions of honor and straight shooting. He imagined far-fetched scenarios: James Baker creeping through the foliage with a phalanx of hungry coon dogs, scaring rabbits out of their hollows

and chasing them toward the pond; Ed Meese, wearing oversize waders and a filthy baseball cap, pulling up to the waterline in a rickety truck with traps full of long-ears foaming at the mouth.

and chasing them toward the pond; Ed Meese, wearing oversize waders and a filthy baseball cap, pulling up to the waterline in a rickety truck with traps full of long-ears foaming at the mouth.

The thing was, said Carter with lazy good humor, he, unlike the Republicans, had long been a friend to the meek and the undefended. Heck, he had signed the Alaska Lands Act. And yet the rabbit had swum against him!

He laughed awkwardly. Clearly he was masking a wound that still ached. I had no doubt the rabbit had affected his conjugal performance.

I'd already put back a good part of the bottle; Carter had barely sipped. I needed a release valve, since my then-wife was attending twelve-step meetings that seemed to consist of a gaggle of hausfraus who had fastened like limpets to the notion that every man jack was a substance abuser. To hear them tell it, a lone Miller Lite in the hand of a spousal equivalentâI use the term advisedly, as there were several lesbians in the groupâwas the equivalent of a Scud missile. Though only dimly aware of the words' definitions, Debbie had armed herself to the teeth with jargon culled from these get-togethers. Terms like

codependent

and

enabling

were thickening the air like poison-tipped arrows.

codependent

and

enabling

were thickening the air like poison-tipped arrows.

“You wish you'd got it, don't you,” I said.

“I'm sorry?”

“The rabbit. Hit your mark, man. Instead of missing.”

Carter stared at me with his mouth agape. In that moment, the ex-free-world leader looked like a village idiot.

“Would have read better,” I went on. “In the history books. You're afraid your name will bear the stigma of that moment of weakness. Of your symbolic impotence.”

“Gosh, I . . .” He trailed off.

The inability to speak at all is, in my line of work, highly significant. I had to press home my advantage.

“I know what you're thinking,” I said. In a session I would never say this, of course, but we were old familiars, after all, and I felt myself homing in. “Maybe Reagan wouldn't have won at all. Maybe you'd still be president now. If you'd hit it. Who knows? Maybe the hostages woulda come home in time. Maybe you'd be more successful in other areas, too. If you know what I mean.”

The pause lasted a while.

Then:

“Well, Bob,” drawled Carter. “Now, you may just be right. But the thing is, I didn't miss. I wasn't trying to hit that poor critter at all.”

And just like that, the rabbit faded. Slowly but surely I knew the dark form of the old Mullins cat, strung up and skinned. Only had two and a half legs to begin with, limped around everywhere; that was why we hated it. Pitiful. Thing made you want to weep.

We trapped it in a corner, Al Jr., Travis, me, and J. C. Whose idea had it been to club it to death in the first place?

Not his.

“Listen. It was all of us that did it, Robert,” came Carter's voice faintly. The wine made my head heavy; it wanted to loll. “Sure, you did the . . . you know, first hitâbut the guys were egging you on. I hope you understand you don't have to bear the burden alone. There was a mob mentality. I mean, the hardness of those times took a toll on us kids. I don't believe it was your fault alone. I really don't. I know we were just children. But I want you to know that I am deeply sorry we did not all step forward to take responsibility. I think how you were punished, and I feel for you. I will always be profoundly repentant for what we boys did.”

Carter was playing hard at deflection. He'd brought out the big guns.

“What you may want to do at this point is visualize

the rabbit,” I said. My mind was wandering. Al Jr. had said we would end its suffering, put it out of its misery. Strength is the principle, now as it was then. Don't cave, I told myself. Do not fall prey to Carter's feebleness. For a while he had governed the nation, but weakness toppled him in the end. The rolling gait of the cat came to mind, how quickly it could get where it was going on its less than three legs. Old Mullins had pulled it around on a plywood cart with a string, but it didn't need the cart. Even when it had been broadsided by the bat, it had struggled to get up again.

the rabbit,” I said. My mind was wandering. Al Jr. had said we would end its suffering, put it out of its misery. Strength is the principle, now as it was then. Don't cave, I told myself. Do not fall prey to Carter's feebleness. For a while he had governed the nation, but weakness toppled him in the end. The rolling gait of the cat came to mind, how quickly it could get where it was going on its less than three legs. Old Mullins had pulled it around on a plywood cart with a string, but it didn't need the cart. Even when it had been broadsided by the bat, it had struggled to get up again.

In quiet times, when memory floated, I imagined that little cat had been brave.

Quiet times brought on sentimentality.

I looked at Carter, the smudged glass globe against my fingers. Behind my hand the near-empty bottle was a column of light. Carter himself stretched sideways and ballooned as though in a funhouse mirror . . . it came to me in a wash of smells and color, that scene in the alley.

He hadn't hit it. Not once.

There he was beside me, thin and bulgy-eyed. He shook his head, tried to stop the whole deal. Because it was my idea, I was up to bat first. He had put up

his hands to grab the bat from me, fell back when I pushed against his chest and stumbled away as I raised the implement.

his hands to grab the bat from me, fell back when I pushed against his chest and stumbled away as I raised the implement.

Down it went. Down it went.

He had never joined in.

“You need to visualize the rabbit,” I said, shoring up my supports. My words were not slurring. I've always held my liquor. “Fix it firmly in your mind. The rabbit is what defeats us in the end, no matter what we do.” I saw a leaden pinpoint shrinking inward; I saw dry motes of dust, the gray hours. Then my eyes glanced across Carter. In passing it came to me how sad he looked. My eloquence was moving him. Possibly, just possibly, he would be able to let go.

Back then I was advising clients to use punching bags for aggression, often with images taped to them. It was an innovative therapy and independently pioneered. But Carter was fairly sophisticated, and I felt instinctively it would be better to keep the self-expression abstract.

“So what are you going to do with the rabbit? Now that you have it? It's in your sights, Mr. President. What are you going to do?”

For a time there was another pause, Carter seeming to gaze at me.

Before long he stood. “You know, friend,” he said in his gentle voice, “all of Creation is under this blue dome of sky. Maybe someone tossed up that bunny's burrow with a plow blade; maybe it had a litter a coyote got into. There are animals that go mad if you kill off their young. Heck, swamp rabbits live maybe two years, if they're lucky. Reckon that poor fella's bones are somewhere near that pond as we speak, covered up in good old Georgia dirt.”

At this point he clapped me on the shoulder. I noticed his glass was still practically full: a good three fingers of the good Ãchézeaux. Was it going begging?

Something in his bearing was lighter. I understood that he was leaving. He wouldn't need to lean on me again. He'd gotten what he came for.

And, sure enough, he would go on to a resurrection. He would rise from the ashes of a failed presidency to attain the stature of a well-respected elder statesman. It's the job of men like me, behind the scenes, to shape and position; sometimes only a nudge is needed. Meanwhile, the public faces of our strengthâour avatars, so to speakâare held up as heroes.

But we know what we do.

I took the presidential hand and held it.

Finally it was withdrawn.

“I appreciate you seeing me,” he said warmly. “You let me know if you ever need anything.”

With that he turned and stepped away. And did I whisper it, or did it only run silently through me?

Out of its misery

.

Out of its misery

.

As he disappeared through the glass doors I stayed where I was, standing. The afternoon had been intense, and I couldn't risk stumbling. It occurred to me he had a point, partly. I was the fall guy for doing what had to be done. I bore the weight of other men's hesitation.

I saw the fullness of the three fingers then. Carter had left me with something.

The Lady and the Dragon

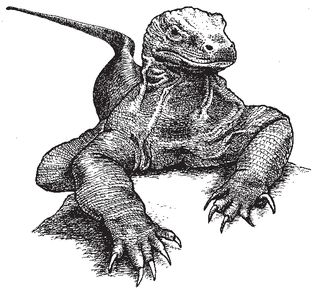

THERE WAS REJOICING AMONG media watchers when prominent newspaperman Phil Bronstein, then the husband of actress Sharon Stone, was bitten on the foot by a Komodo dragon.

The attack occurred at the Los Angeles Zoo, where the celebrity couple was touring behind the scenes so that Bronstein, reportedly an admirer of fierce carnivores, could get a close view of the ten-foot Indonesian lizard. It happened with lightning speed: Just as Bronstein stepped near the giant reptile to pose for a photo, “Komo” the dragon bit him. Jaws clamped rigidly onto the editor's foot had to be wrenched off; the bite severed tendons and necessitated the surgical reconstruction of his big toe. Still, it was widely regarded as comic, and

tabloid reports of the incident belie a barely suppressed delight.

tabloid reports of the incident belie a barely suppressed delight.

Had Bronstein not been married to Sharon Stone, his misfortune would surely have garnered more sympathy than derision, if far less press. As editor of the

San Francisco Chronicle

, he was successful but hardly a celebrity in his own right. But the joke was a clear one: The man-eating lizard was a perfect proxy for Stone herself.

San Francisco Chronicle

, he was successful but hardly a celebrity in his own right. But the joke was a clear one: The man-eating lizard was a perfect proxy for Stone herself.

Bronstein's entry into the cage of the lizard was managed by zookeepers, who recommended the editor remove his shoes, lest Komo mistake them for the white rats that were a staple of his diet. And though the keepers' judgment in allowing the lizard and the barefooted man into such close proximity might have seemed an invitation to litigation, publicly the couple was sanguine about the episode, with Bronstein taking responsibility for his decision to enter the exhibit and joking about the encounter. In television interviews Stone blamed neither the zoo nor the reptile.

Other books

Indebted: The Premonition Series by Bartol, Amy

One for the Morning Glory by John Barnes

a Coyote's in the House (2004) by Leonard, Elmore

I Want You to Shut the F#ck Up by D.L. Hughley

Elizabeth by Philippa Jones

A Murder of Quality by John le Carre

Man of the Trees by Hilary Preston

UnStrung by Neal Shusterman, Michelle Knowlden

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K. Dick

Erotica from Penthouse by Marco Vassi