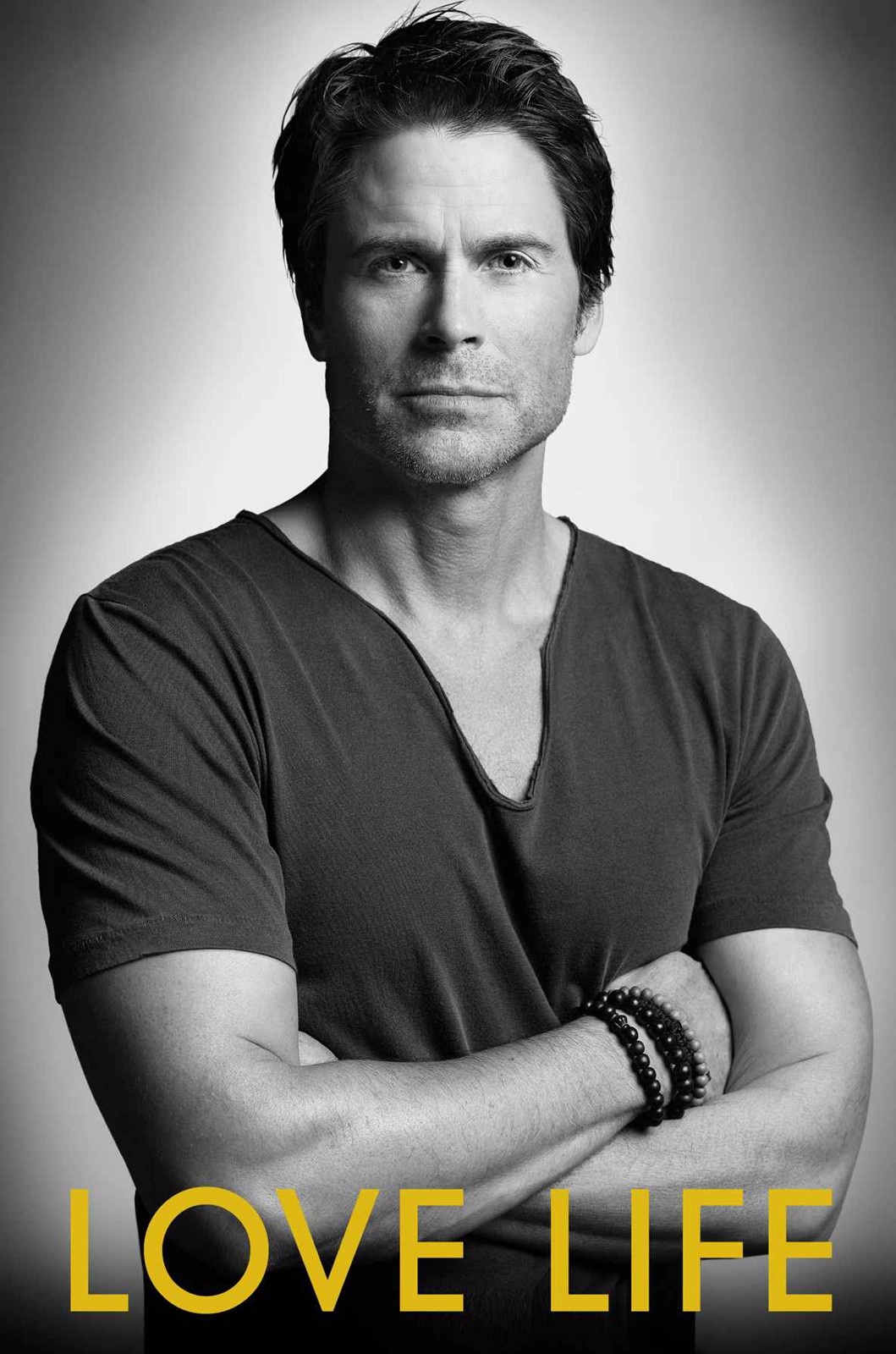

Love Life

Authors: Rob Lowe

Tags: #Actor, #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Movie Star, #Nonfiction, #Personal Memoirs, #Retail

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Characters of Malibu, Icons of the Valley

Stories I Only Tell My Friends

Excerpt

To Lovey

I

think it was Alfred

Hitchcock who said 90 percent of successful moviemaking is in the casting. The same is true in life. Who you are exposed to, who you choose to surround yourself with, is a unique variable in all of our experiences and it is hugely important in making us who we are. Seek out interesting characters, tough adversaries and strong mentors and your life can be rich, textured, highly entertaining and successful, like a Best Picture winner. Surround yourself with dullards, people of vanilla safety and unextraordinary ease, and you may find your life going straight to DVD.

To be fair, early on, we often have less of a say in the casting of our lives. We don’t choose our parents or our schools. And that is where we are formed; it is certainly where I learned some fundamental truths. Not the least of which is this:

You never forget the first time you find a woman’s vibrator.

My brother Chad and I were rummaging around our pal Danny’s tree house–like cottage that he shared with his single mom. I was

thirteen; my brother and his friend were around nine. I had taken to co-opting my brother’s friends in those early days after our arrival in Malibu because thirteen-year-olds thought boys who wanted to “act” were probably “queer,” but nine-year-olds held no judgments about my career aspirations. Chad and I had always been close, bonded by a tumultuous cross-country uprooting and the divorce that instigated it; if he resented my glomming on to his friends, he never showed it.

Chad, Danny and I spent our free time attempting to “shoot” the hill on Larkspur Lane on our skateboards and hiding perishable items among the shelves of our local market, to monitor as they rotted and began to stink. Danny’s mom worked at the checkout counter and every boy I knew had a confused, early-adolescent, dim-witted crush on her. With her sandy hair, light eyes and girlish body, it was often hard to reconcile her hippie-dippy, surf-babe looks with the fact that she was our buddy’s mother. Long before the term had been invented, she was the original MILF.

One day, sitting on her waterbed with its leopard-print sheets, watching

Gilligan’s Island

on a tiny black and white TV, I had rolled over onto a strange, white, missile-shaped device. It began to buzz and vibrate; I began to examine the mysterious obelisk closely.

I don’t think any of the three of us knew what it was, but between the location in which it was found, its shape and the sickly expression on Danny’s face, there was an unspoken consensus to investigate no further. I daintily hid the thing back under the sheets where I found it and we never spoke of the incident. Lesson: Sometimes it’s best to just “move on.”

Like so many in the post-Woodstock, pre-AIDS, ERA-and-EST-driven era of midseventies Malibu, Danny’s mom was no stranger to countercultural mores. After school one day, as the three of us sat eating her homemade avocado pie, she asked my nine-year-old brother if he wanted to be “smoked out.” Chad looked at me with what today

would be called a “WTF?” look, having no idea what was being offered to him. We knew that Danny was a cannabis early adopter, but Chad and I were still sons of the Midwest; we were petrified of drugs. So far.

We were in the minority. If there is one thing that a newly transplanted misfit teen doesn’t want to be, it’s that: standing on the outside of a peer circle. So, after observing the popular kids whipping out their bongs and pipes after a tough day in woodshop or madrigals, I knew what I had to do to ingratiate myself to my fellow thirteen-year-olds. I hopped the bus to Malibu’s only record store for a little shopping spree.

I always liked riding the bus. Because I rode them frequently into Hollywood for my auditions, I knew most of the drivers by name. I particularly liked the ones who let my friends and me hang upside down like monkeys from the overhead safety bars, swinging wildly as we sped down the Pacific Coast Highway.

At the record shop, standing in front of the glass case containing the various dope-smoking accouterments, I decided on a tiny, pocket-sized wooden pot pipe, mostly because it looked like one of Captain Kirk’s phasers from

Star Trek

. And in truth, over the coming weeks I got more use out of it as a toy, running through the sage-scented gullies and swales of the Malibu hills pretending to be shooting Klingons, than I did using it for its intended purpose. Because my dark secret was that I hated pot.

My “prop” pipe did the trick and I didn’t have to smoke at the bus stop in the morning to be cool. I would pull it out of my pocket and brandish it like I was Bob Marley, and eventually the other kids would be too stoned to notice that I never actually used it. I suppose it was an early bit of acting on my part, and it got results; presenting a façade would become a tool I would use to cope with the necessity of “fitting in” (to poor effect) up until my midtwenties.

Malibu in the mid- to late seventies was a breeding ground for many artists who would shape the next decade. There were other young actors to come out of that time and place, and I think it had a lot to do with being surrounded by an unrelenting fusillade of characters and quacks.

This may have been one of the reasons my mother chose Malibu as our new home in the first place. An expatriate from the land of Midwestern, Eisenhower, country-club values, she flourished among the experimental ideas she now found everywhere she turned. My brother and I were unwitting passengers on her lifelong anthropological odyssey.

For example, when my brother was not feeling well, she would accompany him to her favorite doctor. (For reasons I’ve never understood but am thankful for, my mother rarely involved me in her medical extravaganzas.) The doctor wore corduroy OP shorts and an open-chested Hawaiian shirt. He was suspiciously handsome and insisted that all his patients call him by his first name. His practice was based in a tiny walk-up office a block away from the lone shopping center in town. He had no visible staff. His preferred method of treatment for my brother would be to have him hold various types and sizes of crystals while he manipulated my

mother’s

arms, testing her strength in reaction to questions he would ask her about my brother’s health.

“Let’s see about his gallbladder,” he would intone, pressing down on my mom’s outstretched arm. If he was able to move it in a way he deemed abnormal, he would pronounce his diagnosis: “Clearly, Chad has an inflamed gallbladder.”

The prescription was usually a round of herbal remedies, which he sold us by the boatload. He also often required us to “rent” his crystals for a number of days; we would pay the fee, lug them

home for a while and then return them. I have no recollection of them doing anything other than sitting in my mom’s study collecting dust.

I didn’t judge it then; I judge it even less now. I know of an unbelievably talented A-list actor whose oeuvre runs from drama to comedy to comic book action hero. Like the president of the United States, he is never out of arm’s reach of a top secret black briefcase. His daily, hand-chosen battery of exotic (and hugely expensive) crystals provides him with more comfort and power than the launch codes of our nuclear arsenal give to POTUS. Whatever works for you, I suppose.

Although even I have my limits.

People don’t realize how banged up you can get making TV and movies. I wouldn’t compare it to a tour in Afghanistan, but try taking a full week of all-day riding lessons if you’ve never been on a horse. Or a three-week crash course of martial arts, grappling and hand-to-hand combat training. Clearly there are more physically demanding jobs in the world, but you often don’t expect preparing for a role to kick the shit out of you in the fashion of, say, the professional rodeo. But it can.

After one such character prep, I found myself with some pain in my lower back. As I asked around, the best and the brightest minds of Hollywood kept mentioning the name of the same specialist located in Santa Monica.

“This man is a genius!”

“I had been scheduled for a disk fusion and after four visits, I didn’t need surgery!”

I made an appointment.

I almost immediately began to feel uneasy when, once again, the guy had no staff and a cubbyhole office up a flight of stairs. The

good doctor looked exactly like the photo double for Fu Manchu, complete with long, wispy, pubic-hair-looking goatee and mustache.

“Take off clothes!” he practically barked at me, pointing to the massage table.

I began to think of all the Hollywood glitterati who had recommended him. Did he frog-march

them

naked to this flimsy table as well? Not yet knowing the great and extremely useful axiom “Just because someone has an Oscar doesn’t mean they know anything about anything,” I dutifully stripped and dove onto the table.

For the next hour and a half the guy did nothing but move his hands in strange motions over my body. In ninety minutes he never laid a hand on me (I probably should have been grateful)—no massage, chiropractic adjustments, acupuncture needles or any other type of treatment, just his hands relentlessly moving in the air over my back in little circles, like some demented deejay spinning records. Eventually I left in as much pain as I had been in when I arrived, minus two hundred dollars cash.