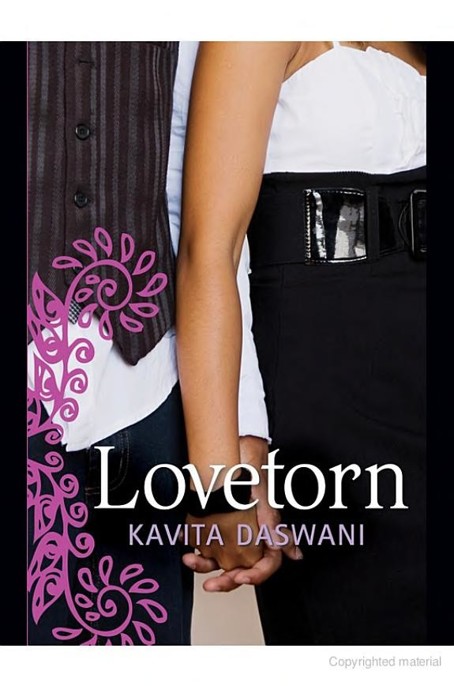

Lovetorn

Authors: Kavita Daswani

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #People & Places, #United States, #Other, #Social Issues, #Adolescence, #New Experience

Lovetorn

KAVITA DASWANI

Dedication

For my husband, my Nissim,

the kindest man I have ever known

And our little boys, Jahan and Nirvan,

who understood when I couldn’t come out to play

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Glossary

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

IN A CARVED WOODEN FRAME

on my mother’s bedside table sits a photograph of me taken on the day that I got engaged. I was dressed all in white, layers of stiff tulle peeking through my skirt, a pink satin sash askew around my waist. My thick hair had been cut short so that the top of it stuck up stubbornly, disappearing under part of the frame. I had tiny gold studs in my ears. I was looking directly into the camera, a toothy smile on my face conveying the exhausted glee that accompanies the final moments of a three-year-old’s birthday party.

My

birthday party.

That image popped into my mind now, and I wondered if my mother had packed the photo in one of the two suitcases she had been allotted by my father for this trip. Sitting in the back of a car as we were driven away from Los Angeles International Airport to our new home on the outskirts of the city, I turned to ask her. But I thought better of it when I saw how sullen she looked. On the other side of me, my younger sister had dozed off, whistling gently through her nostrils. I slid down in the leather seat and rested my head against my mother’s shoulder, turning slightly to take in the scenes whizzing past our window: the fast-food restaurants on almost every corner, the gas stations, the small shops advertising liquor and phone cards and lottery tickets. Long, immaculate highways stretched overhead, seeming to arch into the light blue sky. It was a brilliant, beautiful day.

I should have been utterly exhilarated. A sense of delight and wonder should have been coursing through my body. This was my first time in America, the only trip I had ever taken outside of my homeland of India. There was a new job for my father and a brand-new school for my sister, Sangita, and me. The prospect of this second life had been so alluring to my father that he had given up everything in India for it.

My father, sitting in the passenger seat next to the driver, was reading a copy of

Newsweek

that he had carried off the plane. This was his second trip in a month. He had come to Los Angeles on his own a few weeks ago to sign a lease on a house and fill out the paperwork at our new school. He had wanted to remain in the US and have my mother and sister and me meet him here. But instead, he had flown all the way back to Bangalore last week to help us pack up and to accompany us to our new home. My mother had insisted on it. And she had been so dead set against making the move that my father convinced himself, in this one instance, that he had to do as she’d asked.

“The weather has been wonderful,” my father said to us now, tucking the magazine into a bag at his feet. “It gets a little cool in the evenings, but the daytime is very pleasant.” He was trying to make small talk. “I have been busy here, making sure everything is ready for you. Setting up phones, internet, cable service. Opening bank accounts. Arranging your matters at the school. The house is very nice and comfortable. I was lucky to have found something furnished. Makes everything so much easier.” He had his head turned toward the three of us in the back. My mother, her arms folded in front of her, silent, stared out of the window.

We were in the back of a yellow cab driven by a man my father kept calling Mr. Phil. (We are nothing if not unfailingly polite.) On my father’s first trip here, he had happened to flag him down at the airport. Since then, my father asked for him whenever he called the cab company. As he explained to us, it wasn’t like Bangalore, where you could step outside your home and signal to a passing auto-rickshaw. There were no taxis available in Los Angeles without calling ahead.

“We’re lucky; there isn’t much traffic,” said Mr. Phil. He had a shiny bald head and wore an oversize watch on a red strap. The cab smelled of pine trees. “It’s usually pretty bad on a Friday, but it’s early yet. Maybe another thirty minutes or so and we should be off the One-oh-One.” My father nodded knowledgeably.

I turned to my mother again.

“Don’t worry, Ma,” I whispered, trying to infuse some cheer into my voice. “Everything will be fine.”

I put my hand on top of hers. A pallid ray of late-morning sunlight flashed against the slender ruby ring I wore on the middle finger of my right hand. I closed my eyes for a second to ward off the dull ache that was beginning to close around my heart, a sadness that existed because I had left behind the boy who had given me the ring, the boy to whom I had been promised when I was a baby, the boy to whom I was engaged.

Vikram was the person of all the many, many people I had left behind whom I had already started to miss the most. Since the day I had turned three, thirteen years ago, when he was already a “big boy” at six, we had been a constant in each other’s lives. We had promised to email and text and talk all the time. But he was still twelve-and-a-half hours ahead of me. He would be asleep when I was awake, and vice versa. How could we ever really connect that way? And not seeing him for two years . . . I didn’t know how I would survive it.

My eyes were growing heavy now. I closed them and succumbed to sleep.

When I awoke, we were pulling up outside our new home. My father had shown us pictures of it when he had returned to Bangalore to bring us here. He had been so excited. Now, looking at it through the window, I realized that this house at 21723 Fillmore Lane was almost identical to just about every other house on this quiet street. It was a pale beige color with a white door and a dark red tile roof. It looked like the houses I had seen in American cartoons when I was younger, where life was perfect, people were harmless, everybody was happy.

We pulled up outside. Mr. Phil helped my father get the luggage out of the trunk. I realized that this would be the first time in the course of my sixteen years that I would be entering a home where there would be nobody to greet me. My father had walked up the few steps leading to the front door and was jiggling a key in the keyhole, trying to unlock the door.

“It sometimes gets stuck,” my father said a little sheepishly. “I will call the landlord to fix it.”

My mother looked like she was about to erupt in fury. She didn’t want to be here. She had railed hard against my father’s decision—she and the rest of the large, involved family into which I had been born. It was ridiculous, she had told him. Moving thousands of miles away to a country where we didn’t know a soul. It made no sense.

But my father had not listened to her. This was something he

had

to do. It was a career-making job, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. He wanted eventually to be like the tens of thousands of smart and upwardly mobile Indian executives working in India who referred to themselves as “America-returns.” They had cachet now because they had worked in a country that was hard to emigrate to and in which it was not easy to find a good, well-paying job. But he had landed one—with a company called Indo-West Systems, a software company that he had had some dealings with in Bangalore. It was too good to pass up, even though his decision had come as such a shock to my grandfather that the two of them didn’t speak for three days.

Now, waiting for my father to open the door, it was evident that my mother had already had enough. Her hands were clasped firmly in front of her, and she was muttering Hindi curse words beneath her breath. Just when she was about to say something aloud, he finally managed to turn the doorknob.

Mr. Phil gathered our things and pulled them over the threshold and into the house. We stood there, our belongings heaped around our feet. Now, finally, everything became real to me. Up until now, this talk of a “new life” had felt like a dream. But here it was, in the form of a hardwood floor entryway, a cream-carpeted dining room to one side, another room containing the largest TV I had ever seen in my life. A flight of stairs was toward the back, leading to some bedrooms upstairs. The sun was high and bright now, its rays bouncing off the brass light fixtures. Sangita excitedly grabbed my mother by her wrist and dragged her off to explore.

“Thank you for your kind courtesy once again,” said my father to Mr. Phil. He reached into his wallet and pulled out a clutch of bills, which he handed to the driver. After Mr. Phil left, my father said to me, “What I gave as a tip would cover a full taxi ride in Bangalore.” He laughed. I smiled weakly. My mind was elsewhere.