Lucky Man (28 page)

Authors: Michael J. Fox

“Once the frame's on, but before it's bolted to the table, we wheel you out of the O.R. to the Magnetic Resonance Imaging machine.”

“Let me ask a question,” Tracy interjected. “You do the MRI

after

the frame is on? I thought you couldn't bring metal anywhere near one of those machines.”

“That's true, but the frame we use is aluminum,” Dr. Cook answered. “It's nonferrous, which means it doesn't respond to the magnets.”

Tra

, I was impressed,

good catch

.

“We do the MRI scan to find the VIM nucleus. We also see the areas we want to avoidâthe internal capsule containing all of the information responsible for movement that goes from your brain down the spinal cord. If this internal capsule is damaged, there's a risk of paralysis.

“Next we go back to the operating room, fasten the frame to the table, and raise you on an incline, almost as if you're sitting in a La-Z-Boy. Now we drill the hole in your skull and use a microelectrodeâa long tube with a narrow tip encasing a filamentâto explore the area. The electrode allows us to pick up the electrical signals that the brain cells make and see them on a computer screen. The signals are incredibly small and weakâthis is the electrical output of just one or two cells. The least little signal from any electrical equipment causes a huge interference, so we have to turn off everything else in the room, even the lights.”

“I'm sorry,” I interrupted. “But I don't remember hearing this part before. You're going to operate on my brain with the

lights out

?” I pictured a cadre of medieval barbers trepanning my skull by candlelight.

Dr. Cook smiled reassuringly. “Conveniently, there's a large wall of windows in this operating room.”

Low tech meets high tech

, I thought. Ever since, I have been scrupulous about turning off my cell phone in hospitals.

The doctor continued. “We pass the electrode down through the thalamus and look for the characteristic signals. As we listen to the cells and do things like touch your finger, for example, we look for responses on the computer screen. What we're looking for is a spot where we get a response only when we touch the thumb and index finger because that is the area directly behind our target area.

“The next step is to run an electrical current through the electrode and ask you if you experience any feeling, tingling, or numbness in your thumb and index finger. This is why you have to be conscious. When we get that response, we're directly behind the spot we want to be.

“We like to find that spot as quickly as possible, because each time you probe a new track with the electrode, you add a new risk.”

“Exactly what are those risks?”âMom, this time. But I could tell from Tracy's body English that she was only a millisecond behind with her own version of the same question.

“The biggest risk is bleeding in the brain from the various probes. Overall, the national estimate is a one in one hundred risk of causing any degree of bleeding, but with the microelectrodes we'll use, it's very very rare. The rest of the risks are paralysis, as I've already mentioned, numbness, garbled speech, and an inability to swallow and control secretions.”

There was a brief pause in which I could feel all the eyes in the room turn to me. I smiled, radiating, I'm sure, a genuine and heartfelt confidence. I was well aware of the risks, and while I didn't take them lightly, I felt they were far outweighed by the potential benefits.

“It's okay, Doc, you can keep going.”

“Now we move forward three millimeters from the spot where we get that good response. We put some current into the electrode; if we've hit the right spot, this will temporarily stop the tremor. That's a very good sign. The only thing left to do then is to put in a slightly larger electrode, with enough power to make the lesionâto kill the target cells. When we turn up this macroelectrode, it may cause your speech to temporarily garble, because the current spreads beyond the target area. But first we perform a test by heating up the probe a couple of degrees, enough to stop the activity but not enough to cause a lesion. We examine you to make sure you still have all those functions we don't want to impairâthat you can swallow, speak, and whatnot. This is the patient-participation part of the program. Now we go up to a stronger current until we've heated the target area to the temperature needed to kill the cells. Then, we take the electrode out and you're done.”

Tricky stuff. Everyone fell silent. It was a serious moment, but a phrase I'd tossed off a million times before kept popping into my head:

This isn't brain surgery.

Yet of course this time, it was.

Which got me to wondering:

“Why do

you

think it is . . . ,” I asked Dr. Cook, partly to break the tension, but also because I really wanted to know, “that brain surgery, above all elseâeven rocket scienceâgets singled out as the most challenging of human feats, the one demanding the utmost of human intelligence?”

To my surprise, Dr. Cook actually considered my question for a beat, took a swallow of diet soda, and then offered an answer:

“No margin for error.”

Jesus, he's right,

I realized.

That's it.

I mean, when you think about it, that's probably what gives brain surgeons the edge over rocket scientists. We've all seen

Apollo 13

. Those NASA guys always have the old “plastic bag, cardboard tubing, and duct tape” option to fall back on when the shit hits the fan. Neurosurgeons have no such leeway. What it comes down to is this: if a brain surgeon screws up, it means a multimillion-dollar malpractice suit, but if a rocket scientist screws up, it means a multimillion-dollar hit movie starring Tom Hanks.

No margin for error.

I was still marveling at the perfection of that answer.

He's absolutely right, one little hiccup and . . . So why am I smiling?

Holy Family Hospital, Methuen, Mass.âSunday Morning, March 15

Valium or no valium, I remember things. I remember my head being shaved and asking them to leave some bangs in front so, post-op, I could let them hang out from under my baseball cap and people would think I still had a full head of hair. I remember the stinging pinch of the screws and mumbling something about Torquemada when the aluminum frame was fastened to my skull. I remember a slight vibration, some pressure but no pain, when the tiny hole was drilled through the top of my head.

I rememberâthis must have been a couple hours into the operationâDr. Cook asking me to count to ten out loud. Somewhere between two and four, though, the voice I heard counting sounded as though it was coming from somebody else. A slow baritone warble at first, it suddenly modulated up and down, changing pitches, changing speeds, as if it were a record and some drunk at the party was leaning on the turntable. At eight, I stopped counting.

“

Heyyyy

. . .” I growled in my new

Incredible Hulk

, slow-mo voice, “

You guys are messsssing with my brrrrain.

” I remember them laughing.

And then I remember someone (Dr. Cook?) asking me to put my hand in a position that would cause it to tremor. He wanted me to make my hand tremor, to see it shake. I tried, but my hand wouldn't cooperate. So I moved it again, and it still wouldn't tremor. Now I was getting mad at myself; I felt like I was being a bad patient.

“I'm sorry,” I remember saying (my regular voice back now). “But it won't. I can't make it shake. It just won't do it.”

“Great. That's it,” the doctor said. “We're done.”

I remember lifting my left hand up in front of my face, turning it over and over, splaying out my fingers, obedient and smiling.

That's it. They're done.

Anguilla, the CaribbeanâApril 1998

Another day in paradise.

Dr. Cook cleared me to fly down to the Caribbean with my family just two days after the surgery; it was Sam's spring break. During my two weeks of rest and recuperation, I'd been getting up early every morning, around 6:00

A.M.

, before Tracy, before Sam and the girls, and this day was no exception. I rose from bed quietly without waking Tracy, threw on a pair of shorts and a T-shirt, wrapped my stubbly head (with its comical tufted forelock) in a blue bandana, slipped out the back door of the hotel villa, and made my way down the cliff stairs and onto the beach.

After walking for a quarter mile or so I sat down on the soft white sand and rested my forearms across my knees. Pelicans were fishing about ten feet offshore, wheeling and diving spectacularly, but they weren't the object of my attention. I was focused on my hand. I stared at it, and waited. Inside of five minutes my fingers began to flutter. It was subtle, no one else would ever have noticed, but it was there.

It was just like at the beginning, just like before, with one very big difference: this wasn't my left hand I was looking at. There was no question that the operation had been a success; my left side was as still as the sheltered blue bay in front of me. The problem now was with my rightâthe tremor had moved into the right side of my body. I wasn't surprised. This wasn't altogether new, and had nothing to do with the surgery. In fact, nothing the doctor did that day could have caused this most recent development in my symptoms. The lesion was created in the right hemisphere of my brain and therefore would only have an effect on the left side of my body. I'd actually begun to notice it back in February, after my first meeting with Dr. Cook. Probably the subsiding of the tremor on my left had just made the deterioration on my right side more noticeable.

I was sad, but I wasn't angry. I'd known for years that this was an inevitability. I have Parkinson's disease; it's a progressive disorder. It's just doing what it's supposed to do.

So, what was

I

supposed to do now?

I rose, brushed the sand off the back of my legs, and started to make my way back toward my wife and sleeping children. The answer was clear. After all that I'd been through, after all that I'd learned and all that I'd been given, I was going to do what I had been doing every day for the last few years now: just show up and do the best that I could with whatever lay in front of me.

I picked up some shells for the kids and stuffed them into the pockets of my shorts, and somewhere along the way, as I had almost every day since I'd stopped drinking six years earlier, I said this prayer:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change

Courage to change the things I can

And the wisdom to know the difference.

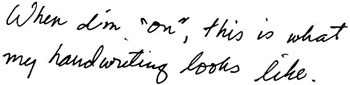

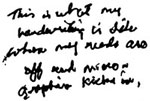

I need to explain the “on-off” phenomenon. This Jekyll-and-Hyde melodrama is a constant vexation for the P.D. patient, especially one as determined as I was to remain closeted. “On” refers to the time when the medication is telling my brain everything it wants to hear. I'm relatively loose and fluid, my mind clear and movements under control. Only a trained observer could detect my Parkinson's. During one of my “off” periods, even the most myopic layperson, while perhaps not able to diagnose P.D. specifically, can recognize that I am in serious trouble.

When I'm “off,” the disease has complete authority over my physical being. I'm utterly in its possession. Sometimes there are flashes of function, and I can be effective at performing basic physical tasks, certainly feeding and dressing myself (though I'll lean toward loafers and pullover sweaters), as well as any chore calling for more brute force than manual dexterity. In my very worst “off” times I experience the full panoply of classic Parkinsonian symptoms: rigidity, shuffling, tremors, lack of balance, diminished small motor control, and the insidious cluster of symptoms that makes communicationâwritten as well as spokenâdifficult and sometimes impossible.

Hypophonia, hypomimia, and “cluttering” can all get in the way of verbally expressing feelings and ideas. Hypophonia weakens the voice so badly that for some, like Muhammad Ali, simply making yourself audible demands a tremendous effort. So far I've been spared that particular challenge. When I'm “off,” my struggle is with “cluttered speech” combined with hypomimia, the medical term for the “mask effect” often observed in the faces of P.D. patients. My ability to form thoughts and ideas into words and sentences is not impaired; the problem is translating those words and sentences into articulate speech. My lips, tongue, and jaw muscles simply won't cooperate. What words I do smuggle through the blockade can be heard, though not always comprehended. Try as I might, I can't inflect my speech to reflect my state of mind. And it's not like I can liven up my halting monotone with a raised eyebrow; my face, utterly expressionless, simply won't respond. Like Emmett Kelly, but without the greasepaint, I often appear sad on the outside while actually smiling, or at least smirking, on the inside.

Micrographia is precisely what it sounds likeâtiny writing. I have a stockbroker friend, a fellow Young Onset patient (amazingly, the friendship predates our diagnoses) whose secretary was the first to recommend he consult a neurologist. Over the course of a year or so, she had found it increasingly difficult to decipher his memos, and finally confronted him with the evidence of his incredible shrinking handwriting. Without drugs, my own penmanship becomes similarly microscopic. Combined with the stubborn refusal of my “off” arm to move in a smooth, lateral, left-to-right direction, the result is a fractured column of miniature scribbles.

This:

Becomes this:

These impediments to self-expression are not the most painful or debilitating features of Parkinson's disease, yet they madden me more than even the most teeth-rattling full body tremor. When the meds are “off” and P.D. has already rendered me a prisoner in my own body, the suspension of my telephone and letter-writing privileges seems excessive.

Then there's the sensation of not being able to settle, or land in any one spot for more than a second or two. When I'm “off,” I feel like I'm dangling from a coat hanger that has been surgically implanted under my skin in the muscles of my back, wedged between my shoulder blades. The sensation is not quite one of being suspended in the air; it's more like being jacked up, with my toes scraping and kicking at the ground, straining for purchase, so that, if only for a moment, both feet can plant firmly and bear the full weight of my body. During the years I spent promoting the fiction that none of this was actually happening to me, my only recourse was to isolate myself and grit it out.

Three to four times every day, I go through the transitions between the two poles, navigating the tricky passage from the land of “off” to “on.” The most surreal aspect of this thrill ride is that during every “on” time, I delude myself into believing that that, and not the other, is my “normal” condition.

None of the pills I take gives me even a mild buzz, but the freedom of movement and the interlude of physical grace they provide are intoxicating. I don't squander a nanosecond of this time contemplating the inconvenient truth that what I'm experiencing is not “real.” I don't think about that when I'm splashing in the surf with Aquinnah and Schuyler, fishing for bass with Sam, or huffing to keep up with Tracy on the bike rides she loves so much. I truly do forget and, lost in this sublime ordinariness, it's easy to miss the subtle twitches, creeping rigidity, and vibrating sensations urging me to crack open the vial and toss back another little blue pill.

Every P.D. patient's experience is unique. Mine is this: If I miss or ignore those early-warning signs, there's no second chance. I am down for the full sixty to ninety minutes. It's no good upping the dosage, eitherâthat only results in exaggerated dyskinesias (random, spastic, hyperextended movements of the extremities) when the L-dopa finally does take effect. As with the “on” period, it is hard to believe that the “off” is ever going to end, and it doesn't help to remind myself that it always does.

Arranging life in order to be “on” in public, and “off” for as little time as possible, is a balancing act for any P.D.er. In my case, the gut-wrenching prospect of losing my balance, figuratively or literally, on

The Late Show,

say, or at a public event where there was no way to avoid close scrutiny, loomed ever larger the longer I remained in the closet.

Learning to titrate medication so that it kicked in before an appearance or performance, sometimes within minutes of my cue, became a process of continuous tweaking and refiningâlots of trial with little room for error. Timing a punchline was a joke if I hadn't timed my meds accurately. I became a virtuoso at manipulating drug intake, so that I'd peak at exactly the right time and place.

When the L-dopa begins to work, and the current “off” segues into a fresh “on,” the sheer relief of the transformation is its own special high. The people close to me are attuned to the physical ceremony that marks my latest transition back into the world of the fully functioningâthe subtle sigh, accompanied by a sudden spastic thrust or two of my left leg, immediately followed by the outstretching of my arms and rolling of my head. The leg thrusts are involuntary but entirely welcome, because they signal the beginning of the end. As the tension leaves my body, it always travels down and through that particular limb, and then into my foot, which rotates three or four times. Finally, as if being pulled by the force of a vacuum, the tension disappears, departing through the sole of my left shoe. The extension of my arms, and rolling of my head, are simply my body's way of celebrating the reunion of mind and motion.

This ritual ending of an “off” period is immediately followed by another personal rite, this one marking the return to “on” status. If you ask Tracy or anyone else who spends a lot of time with me, they will tell you that I do, and say, the same thing every single time: I smile, close my eyes, and then, like Barry White on helium, croon, “oh baby . . . I love it when the drugs kick in.”

“ON,” “OFF”âAND “OUT”

Spin City

Season Threeâ1998

Presenting an accurate snapshot of my symptoms at any one point in time is never easy, but what I've just outlined describes fairly well the body I had to work with at the beginning of

Spin City

's third season. In the months following the thalamotomy, the success of the procedure in taming my left side was a happy and obvious matter of fact. Just as obvious, though, was the rapid escalation of the new tremor on my right sideâworsening at a rate I could track almost on a daily basis. I wonder if the disappearance of the furious flapping in my left arm had also served to throw the other symptoms (rigidity, hypomimia, and the rest) into sharper relief. Whatever the reason, there was no doubt that after a sweet but all-too-brief post-op plateau, my disease was confronting me with a whole new set of challenges, personally as well as professionally. It was also hastening a decision, long postponed, to bring the private and public sides of my life into closer alignment. Keeping my disease secret was rapidly becoming untenableâand destructive.

Most P.D. patients will tell you that stress exacerbates their symptoms, and during the summer of 1998 my job suddenly got a whole lot more stressful. In response to our persistent creative conflicts, Gary Goldberg decided he would not return to the show for the third season, remaining instead in L.A. to be with his family and pursue other projects. Though at the time the split was grueling emotionally, I'm convinced it ultimately preserved our friendshipâin many ways stronger today than ever beforeâand set the stage for a professional reconciliation two years later that would ensure the series' future after my retirement. In the short term, though, I now found myself with the creative authority I'd craved for the first two seasons: a vast increase in my responsibilities.

Be careful what you wish forâ

I was now in charge of the show.

It's not that I didn't have tremendous help. Bill Lawrence returned to the show, as well as writer-producer David Rosenthal, and most of our talented, if eccentric, writers, technical crew, and administrative staff. Andy Cadiff, who had served brilliantly as director during the previous season, was given the added title of

Spin City

producer, and proved an invaluable partner in running the set. Danelle Black, the president of my production company, became a consulting producer, and as the executive closest to me, was inundated with requests for my time and attention. Danelle's skill at running interference for me transcended mere professional responsibilityâthis was loyalty and friendship of the highest order.

Still, I now had countless production issues to oversee and decisions to sign off on during each twelve-to-fourteen-hour day: rewrites for that week's episode, outlines and story arcs for scripts weeks in advance, casting and crew hirings, wardrobe and set consultations, music and editing oversight, and the continued tending of diplomatic relationships with the network and studio. All of this I enjoyed. Well,

almost

all of it: my least favorite duty, as a lifelong hater of mathematical absolutes, was establishing and then sticking to a weekly production budget.

As demanding as all this was for me, I was beginning to appreciate how truly difficult I was making life for the people I worked withâthe majority of whom didn't know about my health issues. I'm thinking of all the times my symptoms forced me to reschedule appointments at the last minute with various department heads, only to have to reschedule again and again, and sometimes ultimately cancel with no explanation. My behavior must have seemed flaky at best, and at worst arrogant and disrespectful. The many last-minute production delays, running anywhere from a few minutes to a half an hour or more, that I usually blamed on some vague injury or “important phone call from the West Coast,” must have been a source of mystery and annoyance. Not that it was any easier for those who knew what was really going on. Danelle, Bill, Andy, the cast, and the handful of others I had let in on my secret were under constant pressure to cover for me, to come up with fresh excuses and, if they didn't have time to check their stories against mine, worry they were going to betray my confidence by being caught in the whitest of lies.

There were already rumors, of this I was well aware. Some of them originated, I suspect, in Boston. My frequent visits to that city for medical treatment and consultation had somehow been brought to the attention of a pair of local newspaper gossip columnists.

They were the first, I believe, to link me to some vague and undefined “mystery” illnessâas far back as 1997. To their great indignation, I basically ignored them, and because their speculation was so unspecific, these mentions gained little wider attention. It wasn't until 1998 that the national tabloids cautiously picked up on the story. They printed a few items, at first blind, and then some that referred to me directly as having been stricken by an unknown illness and currently undergoing treatment.