Lucky Man (9 page)

Authors: Michael J. Fox

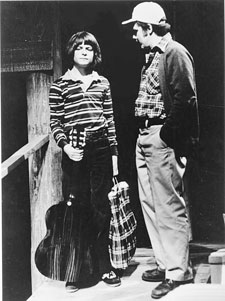

A massive open audition, “a cattle call,” in showbiz parlance, the search for the kid co-star of the new CBC situation comedy

Leo & Me

offered a one in a thousand shot at the job. I wanted to do it even if it did mean playing a twelve-year-old. Ross was right: here was payback for all the years of short jokes. As the day of the tryout neared, my confidence grew. My mom gave me a ride to the CBC studios in downtown Vancouver. When we walked in the door, a receptionist handed me a script. Scanning the room, packed with young hopefuls and their doting mothers, I searched for a couple of chairs where we could sit down and I could study my lines. I read the words on the pages, quickly understood where the jokes were intended to be, and silently ran through them in my mind.

This is how my mom remembers it: “There were all these little kids in there and mothers were fussing with their hair, but you wouldn't let me touch yours. The kids were all practicing their lines with their mothers, so I asked, âDo you want to go through the lines with me?' âNope. I'm okay. I'm okay.' You just took it all so in stride.”

Leo & Me

, explained the director, would be a half-hour comedy about a thirty-something gambler who lives on a run-down yacht won in a poker game. Leo's playboy lifestyle is cramped when he unexpectedly inherits guardianship of a twelve-year-old nephew, Jamieâthe “me” of the show's title. I hadn't given any thought about how to tell the director, producers, and other network types present at the audition, that I was, in fact, sixteen and not twelve. Was this going to be a problem? It became a moot point during the small talk after my reading, which they liked. I let slip how pissed off I was after flunking my driver's test for the second time. “It's discrimination,” I fumed. “The minute you lay a phonebook on the driver's seat, they just check the fail box.” They kept asking me follow-up questions, and the more humiliating details I disclosed, the more flat-out hilarious they found the entire story.

Who cares how old the kid is

, they must have thought,

he's a riot

.

“When you got the callback, and then the part, well, it was just surreal,” Mom marvels. “I couldn't believe it.” She couldn't, but I could.

In addition to the lead in the series, which would begin filming later that summer, I was also offered the lead role in a separate project, a TV film that would begin production shortly after I got out of school. It was that easy. After making $600 for the entire summer the year before, I would now be getting a check for $600 every week. That summer, between the eight episodes of

Leo & Me

and the TV movie, I pulled in almost six grand.

I mention the money because when people ask how it was that, given my many interests, it was acting that I ultimately decided to pursue, I'll laugh and give the glib but essentially honest reply: “It was the first thing I got paid any real money for.” In 1977, for a sixteen-year-old, working-class Canadian kid, an army brat, $6,000 was a

shitload

of cash. But that's really only part of the answer.

I enjoyed the experience, the creative process, and as much as anything else, the working environment on the set. For the first time I was accepted as an equal among adultsâpeople with far more experience than I had, who recognized in me abilities that I had not known I possessed and helped me to nurture them. This applied not only to my fellow actors, or the producers and directors, but to the seemingly endless numbers of peopleâgaffers, sound engineers, camera crew, hair and makeup people, and all the othersâthat it takes to make a TV show.

When the cameras weren't rolling it seemed as if we were always laughing, and the tone of the humor was often darker, more complicated and irreverent than anything I'd known. These artists and artisans occupied a world apart from the sober and serious sort of workplace most adults I knew had resigned themselves to. These were the people my father had warned me about. I was home.

In the fall of 1977, I entered high school (which in Canada begins in the eleventh grade) with a new confidenceânot in my ability to meet a new level of academic challenge, but in the conviction that school was, more than ever, irrelevant to me. Throughout the eleventh grade, I continued to pick up acting jobs, commercials, radio work, and guest spots on other CBC television series. It became more and more difficult to reconcile my burgeoning acting career with what to my mind were the increasingly pointless demands of school. Somehow I muddled through, though by the end of the final semester, I was still technically a few credits short of completing the eleventh grade. If I wanted my high school diploma and hoped to graduate with the rest of the class of 1979, I'd have to repeat those courses in the fall. If eleventh grade was tough, twelfth was going to be killer.

But before that, taking what was left of the summer after

Leo & Me

wrapped, I decided to spend some of my fresh TV money on a trip to California, my first. I'd made a new friend during the previous school year, a senior named Chris Coady. As bright as Andy Hill but with more of an outlaw edge, Coady had an irreverence and a twisted sense of humor that made him my ideal running buddy. The Rolling Stones'

Some Girls

tour would be passing through California in August, and we made plans to go catch the band at Anaheim Stadium. Chris didn't have a lot of cash, so I paid for most of the tripâthe plane tickets, the motel room near Disneylandâand we had a blast. Living it up in the Hotel California, we lounged by the pool, drank watery American beer, and chatted up girls who, like us, had come from various parts of the world to see the Stones. By the day of the concert, we'd run through most of our money and handed over what was left to ticket scalpers. By our last two days there we were completely broke, our only sustenance being the hot chocolate we'd get at a nearby Denny's with the free coupons we scrounged from the motel lobby. I had no idea, of course, that by the following summer I'd actually be living in California. Those few days of pseudo-poverty were a foreshadowing of the two or three years of very real economic hardship I would soon have to endure.

During much of that fall I was, at least ostensibly, going to school by day and performing at night in a long-running hit play at the Vancouver Arts Club, the most prestigious Equity theater company in town. This meant working until well after midnight every night. I would climb out of bed in the morning exhausted, go through the I'm-off-to-class motions, climb into my new pickup truck, and drive to the nearest park. I'd pull under the cool shade of a maple tree, fish a foam pad out of the cab, lay it down in the bed of the truck, and go back to sleep.

My first subject in the morning was drama, and having left the ever-supportive Ross Jones behind in junior high, I found myself in the strange position of receiving solid reviews for my professional acting at the same time I was flunking high school drama for too many absences. Naturally I pointed this irony out to my drama teacher, arguing that I should get credit for the work experience. She wouldn't budge.

By November it became clear that I was flunking just about every class I had. The whole high school thing had become a farce. I talked to my parents and told them I truly did want to graduate, but not at the price of throwing away the promising career I had embarked on. Mom urged me to hang in there, and made me promise that if she and Dad could work out a compromise with the schoolâcredit for work experience combined with tutoring and makeup courses outside of the regular classroomâI would stick with it and do my very best. Surprisingly, my dad sympathized with my frustrations even more than Mom. I was making a living. Indeed, he'd be the first to admit that I was making more in a year than he was. So my parents agreed to fight for me and vowed that if no compromise could be worked out, they would support my decision to leave school and work full-time.

The school administration refused to bend, and to my relief and surprise, my parents held up their end of the bargain. They supported my decision to drop out, despite the fact it had always been their dream to see one of their children go to college.

Why did they let me do it? Well, some of the credit has to go to Nana. “We had no reason to doubt that these opportunities, the plays and the job at the CBC, were what Nana said was gonna happen,” my mother says now. “Because Nana was so strong in her beliefs, if we hadn't followed through and supported your decision, I would have felt like we were letting her down, as well as you. So Dad and I said, âGo for it.'”

With Mom and Dad's blessing I gave notice that I would not be returning for classes in the spring. I made the rounds at school, collecting my things and saying good-bye to friends and those teachers with whom I was still on speaking terms. Their doubt about the wisdom of my decision was nearly unanimous. I remember one exchange in particular, with a social studies teacher. “You're making a big mistake, Fox,” he warned. “You're not going to be cute forever.” I thought about this for a beat, and as I turned to make my escape from his classroomâfrom school and, soon enough, from my life in CanadaâI shot him a smile and replied in a measured tone, “Maybe just long enough, sir. Maybe just long enough.”

U.S. Interstate 5âApril 1979

Here's an unlikely concept for a buddy movie, a sort of late 1970s, cross-generational Farley-Spade road picture: my dad and I driving through the night to California, on our way to Hollywood for my shot at the big time. My sidekick lay stretched out in the rearview mirror, Dad's 250 pounds contorted into the backseat of our 1977 Dodge Aspen. He was catching a little shut-eye while I drove the night shift, following the treacherous twists of Interstate 5 through Oregon's Cascade mountain range. We'd meet the sun as it brimmed over the more hospitable hills of northern California. Now that he was asleep, I could tune out his twenty-four-hour-all-news radio station and tune in the only static-free music I could findânew Doobie Brothers. “What a fool believes, he sees,” crooned Mike McDonald, “no wise man has the power to reason away.”

I remember thinking that night just how far Dad and I had come over the past few weeks. The fact that he was accompanying me to Hollywood, after years of regarding my ambitions from beneath a skeptical brow, was a turn of events I never would have anticipated. Of course his decision to let me bail on school was a gesture that cut both ways: sure, it was a show of support, but it was also, I knew, a challengeâthis was put-up-or-shut-up time. Still, he'd given my clichéd dream of escapeâdropping out of school to chase fame and fortune in Americaâan interesting twist: if I was going to be a runaway, I was going to be a runaway with a chauffeur.

Deciding to make my move that April was the hard part. It meant passing on work I had already lined up for the spring and summer in Vancouver: a German television production of

Huckleberry Finn

. But Toni Howard, an L.A.-based casting director I'd met on an earlier job, had convinced me that the time to strike was now. She believed I held an advantage: American producers would be eager to hire an experienced actor who looked young enough to play a kid, since labor laws made it costly to use actors under eighteen. Spring was also the casting season for TV pilots. It didn't take much to convince me, so supremely confident was I that a Hollywood career was my destiny. But since I wouldn't turn eighteen till June, I'd need my parents to sign off on my planâand that seemed inconceivable.

Mom: “Are you sure this is what you want to do?”

Me: “Absolutely.”

Dad: “You realize what you'd be turning down, right? You're

that

confident?”

Me: “Absolutely.”

And then Dad shocked me.

“Well if you're going to be a lumberjack, you might as well go to the goddamn forest.”

Dad agreed not only to drive me down to L.A., but to underwrite the adventure, putting the whole trip on his Visa card.

“A down payment on my pension plan,” he joked.

I couldn't have been more earnest in my reply: “It's a deal.”

We were off to the goddamn forest.

Los AngelesâApril 1979

As soon as we checked into our room at the Westwood Holiday Inn on Wilshire Boulevard, I hit the phone, confirming sit-downs with agents who said, yes, Toni had been in touch and they were expecting my call. Dad advised me that he'd just drive to the appointments and debrief me after each oneâhis way of signaling to me that this was my show, not his.

My composure was tested during one particularly memorable interview. The agent in the chair across from me seemed distinctly underwhelmed at the prospect of representing me. An awkwardness hung over the office like a methane cloud. For some reason, she couldn't look me in the eyeâher gaze kept drifting down to my feet. Finally, she summoned up the nerve to say what was on her mind, in the process interrupting some of my wittiest patter.

“Listen, Michael, you've got a great look and you're very funny and charming. Toni had wonderful things to say about you, so you're obviously talented. It's just that I don't understand why she didn't mention . . . that is, I wasn't prepared . . . well, I wasn't aware that you had a disability.” And with that her eyes went back down to my feet.

“I don't. At least I don't

think

I do.”

“Then why are you wearing orthopedic shoes?”

Now we were both staring at my feet. Those weren't orthopedic shoes. They weren't shoes at all, in fact, they were bootsâjet black, glam rock, platform boots with four-inch heels and two-inch solesâthe very height of 1970s cool, in my considered opinion. Embarrassed, I managed to laugh it off while assuring her that my only handicap was being a few inches too shortâand, I realized in a sickening flash, several years behind the California fashion curve. Anyway, the cloud quickly evaporated and the rest of the meeting went well.

After rejoining Dad in the office waiting room, we went downstairs to a coffee shop and slipped into a booth. “Well, she wants to sign me too,” I reported. “By the way, can you lend me another fifty bucks? I gotta get a new pair of shoes.”

On the fourth day in Los Angeles, we packed to go home; not because anything had gone wrongâquite the contrary, everything had gone preposterously right. Every agent I met had offered to take me on. Most had sent me out on auditions in order to gauge reaction, polling the casting directors for feedback. Every audition earned a callback, and three of the callbacks produced solid offers. This Hollywood thing was beginning to look easy.

Deciding which role to take was straightforward. Only one movie was scheduled to start production in June, after my eighteenth birthdayâa Disney feature called

Midnight Madness

. The less said about the script, the better, but

Midnight Madness

was my first real job in America, and I was thrilled to have it.

Now, all that was left to do was hire an agent. Dad and I had lunch with the Gersh Agency's Bob Gersh, the agent who'd sent me out on the Disney job. Bob was naturally solicitous of my father's approval, and he asked Dad if he had any questions. My father just smiled, put his big hand on my shoulder, and said, “I prefer to let him do all the talking.” You have no idea just how exotic those words sounded coming from my dad.

“Did you know,” I asked Dad as we left the restaurant in Beverly Hills, “that his father, Phil Gersh, was Bogart's agent?” Dad just shook his head.

Too much

. We drove back to the Holiday Inn, checked out, and loaded our bags into the trunk. One last stop, delivering a pot of flowers to Toni Howard, and we were on the I-5 again, heading north.

Queen Elizabeth Park, New Westminster, B.C.âJune 9, 1979

It was my eighteenth birthday, and I celebrated it back in Vancouver. I had a plane ticket to leave the next morning for Los Angeles and begin work on the Disney picture. Plenty of congratulations and backslaps all around. Mom, Dad, and my sibs were there, of course, as were most of my extended familyâeveryone from the videotape, in fact, with the sad exception of Nana. Chris Coady was present, and so, too, was Diane, the girl I'd been seeing for the previous six months.

The colors in the park that afternoon were jaw dropping. A cobalt sky presided over early summer gardens of pastel pinks and purples. Elsewhere, a dozen different shades of greenâfrom the pale streaks of lichen on streamside boulders to the deep jade of the Douglas firs. In the distance a white-capped mountain range crowned the treetops. This is why the license plates say

Beautiful British Columbia

, and I realized just how much I would miss it. But all this natural beauty exists only in response to rain, I reminded myself, and the occasional day of technicolor spectacle was bought and paid for with weeks and weeks of dull, damp gray. I wasn't going to miss the gray.

If they could have overheard my thoughts that afternoon, my friends and family probably would no doubt have found them silly and self-dramatizing. It was only one movie, after allâone job, six weeks. It's not like I was

moving

to California, they'd say. I'd be back. I knew otherwise, and so, in their hearts, did my mom and dad, especially Dad. He had made a point of telling me on the way back to Canada how well I'd handled myself and how proud he was. “You've got the world by the tail,” he announced while driving north on I-5. “Just hold on.” I realized that for me, the trip we made together to Los Angeles had been a rite of passage, a coming-of-age ceremony, like those in cultures the world over. But unlike many such rites, which often involve abandonment or even scarificationâsome physical evidence of a test or ordeal enduredâmine was not a wounding ritual. Dad had found a way to get past his misgivings and make my rite a ceremony of healing.

Did this mean that on my eighteenth birthday, I had actually come of age? The events of the next fifteen years or so would lead one to a very different conclusion. But on that June ninth in the park, with friends, family, and other well-wishers gathered around, I felt as if I had reached a new level of maturity. There was no question in my mind that I was now indeed a

man

âas I leaned over and blew out the candles on a birthday cake decorated with an image of Mickey Mouse.

OPENING CREDITS

The Slums of Beverly Hillsâ1979â1981

An inventory of my worldly possessions circa 1980: one duffel bag full of clothing (i.e., dirty laundry), one hot plate, some mismatched kitchenware, toiletries, blanket, bed sheets, and a wind-up alarm clock. Oh, and then there was the furniture: one mattress and one folding canvas director's chair.

My studio apartment was seventeen by twelve feet with a microscopic bathroomâtoilet, shower, no tub, and the domicile's one and only sink. The sink basin was too tiny to do dishes in, so I'd have to take them with me into the shower. More than once I washed my hair with Palmolive and my dishes with Head and Shoulders. A closet doubled as the kitchen.

Technically, my address was that of a small pink stucco apartment building on Shirley Place in Beverly Hills, although I rarely saw the building's peaceful, tree-lined street sideâI came and went via the back alley. There was a tiny separate garage structure where tenants would park their cars. My unit was one of the three built into the space above it. My front window gazed across a six-foot-wide pathway at the pink backside of the mother building. Peering through the narrow transom window in the bathroom required standing on top of the toilet seat. With nothing out there but Dumpsters, parked cars, and oil-stained asphalt, the vista did not reward the effort. But for $225 a month with a six-month lease, this was paradise.

My alley marked the boundary between Beverly Hills and Century City, a tight cluster of soaring glass-and-steel office buildings constructed on land that was once the old Twentieth Century Fox back lot. Shirley Place was named for Shirley Temple, Fox's biggest star at the time the maps were redrawn. Sometimes referred to as “the slums of Beverly Hills,” the ring of multi-unit dwellings that circle the more affluent residential areas are actually attractive and luxuriousâby my standards, anyway. People can live in bigger apartments for less money elsewhere in the city, but they covet the 90210 zip code that Aaron Spelling's Beverly Hills High soap opera was going to make world famous. The school itself, which backed up against the end of my alley, reeks of privilege and exclusivity. Just to walk past it can be an intimidating experience, as I discovered the day I bought my folding canvas director's chair.

I'd picked up the chairâmy first big purchaseâfor thirty bucks at Thrifty Drugs. Trekking back toward the apartment,

my home

, the chair slung over my shoulder, I must have looked like a complete rube, a total dink. Just as I was about to make the turn down my alley, a teenager from the high school drove by in a Porsche convertible. Slowing to a crawl, he considered me for a second and then, over the rumble of his turbo-charged engine, shouted, “Go back to the Valley!” I had no idea what he was talking about.

The Valley?

He meant the San Fernando, but for all I knew he was talking about the Fraser River ValleyâCamp Chilliwack.

Life as a fish out of water in Beverly Hills didn't really faze me, though. I'd always been an outsider in one way or another, and L.A.âhell, Americaâseemed like outsider headquarters. As the number of days I spent there added up, so did the number of eccentrics, risk takers, and freethinkers I encountered. Equally captivating was the breathtaking racial and ethnic diversity. As I saw it, California was everything that Canada, with its polite provincialism and reverence for order, could never be. So, far from being alienated, I actually felt at home. The logic of this mecca of nonconformity was this: not fitting in meant that I truly belonged.

Along with a new country, new city, new job, new apartment, and new chair, I'd also picked up a new identity. The Screen Actors Guild prohibits any two members from working under the same stage name, and they already had a “Michael Fox” on the books. My middle name is Andrew, but “Andrew Fox” or “Andy Fox” didn't cut it for me. “Michael A. Fox” was even worse, the word

fox

having recently come into use as a synonym for attractive. (Presumptuous?) It also sounded uncomfortably CanadianâMichael

Eh?

Foxâbut maybe I was just being oversensitive. And then I remembered one of my favorite character actors, Michael J. Pollard, the guileless accomplice in

Bonnie and Clyde

. I stuck in the

J

, which I sometimes tell people stands for either

Jenuine

or

Jenius

, and resubmitted my forms.

So it said Michael J. Fox on the call sheet I picked up at wrap each night that summer, or more accurately, each morning. True to its title,

Midnight Madness

turned out to be an endless series of all-nighters: six weeks of almost exclusively night shoots. The mix of late nights and young actors gave the set a loose frat party ambience. At least we had a few laughsâseveral more, we correctly sensed, than the audience ever would. Personally, I was just happy to be there. So what if I was working all night on a lousy project?âit left my days free to audition for better ones.

Determined to stay in L.A., I hit the pavement looking for future employment. By autumn I'd landed my third post-

Madness

project. My only disappointment was not landing a feature film. I came close on a couple of movies, most notably

Ordinary People

, earning a callback to see the director. But Robert Redford seemed less than impressed by my reading; he spent the audition flossing his teeth. My next big screen role would not be until 1981, the then-futuristically titled

Class of 1984

, a teen exploitation flick that would make

Midnight Madness

look like

Casablanca

.