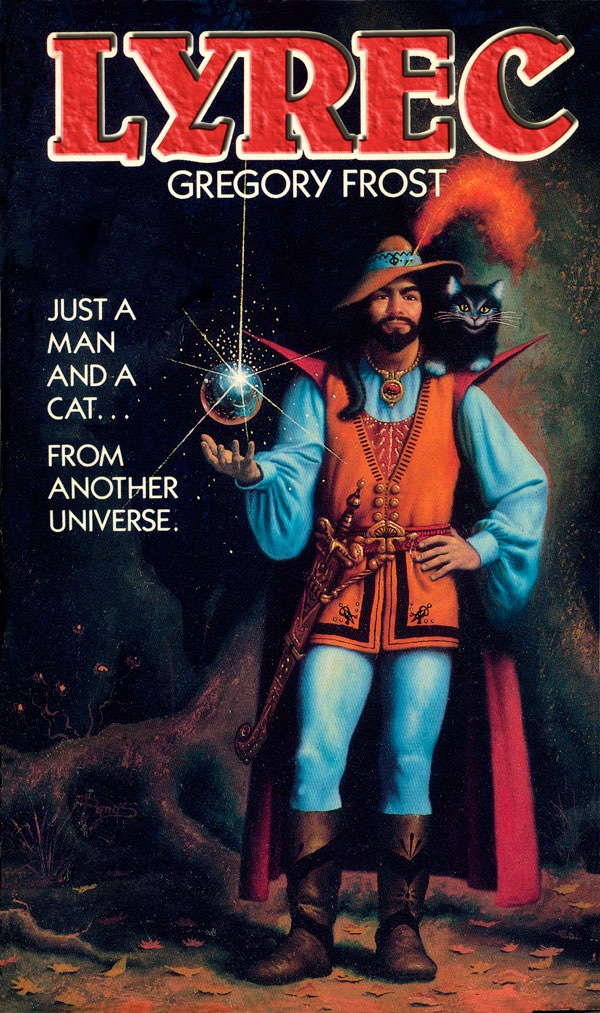

Lyrec

by

Gregory Frost

LYREC

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1984, 2011 by Gregory Frost.

PUBLICATION HISTORY

Ace Original Fantasy 1984

Quolibet eBooks

Edition, © Gregory Frost, June 2011

Cover art by Romas

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, electronically or in print, without the express permission of the author.

ISBN:

978161138 076 7

DEDICATION

In memoriam, to my father and mother, for all the love.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This edition of LYREC would not exist without the kind assistance and advice of members of the SFNovelists group, including Charles Stross, Tobias Buckell, Chris Dolley, and Sarah Zetel. Likewise to everyone at Book View Cafe, including Vonda McIntyre, Pati Nagle, and Judy Tarr.

Finally, to Romas Kukalis for the reuse of the original cover art for LYREC.

To all of you, my undying thanks for your wisdom and skills.

Prologue.

The pink light of dawn wedged between great gray clouds that spread like mountains across the sky.

The low forest scrub—thistled, foul-smelling, yellow freminiad that leather workers used in tanning—cast off a thin mist, which rose in smoky vines like departing floral ghosts.

A flock of birds took wing suddenly, fleeing from the approach of the forest invaders.

The invaders were preceded by the clank of armor and swords, by the slap of reins; by the creak of leather; by the exasperated blowing of horses that disliked being bridled so early. The warning was clear: men had entered Boreshum Forest. One king, his daughter, a cluster of soldiers, and a few trusted servants.

Dekür, the king of Secamelan, rode near the head of the party, with two soldiers before him. His daughter, Lewyn, rode by his side. He looked toward her, saw her proud head tilted back, revealing a strong jaw and slender neck. She was pale and blonde, with her cheeks brightly rouged by the chill air. Seeing the flock of birds take wing, she turned to him, her blue eyes wide with an excitement he could not share this early in the morning. He felt stiff and tired, and a little hung over.

“Beautiful birds, aren’t they?” she said, and he answered, “Yes, very,” then turned away.

Lewyn looked at him covertly in a way that children sometimes do, but he did not see.

He knew some of what she felt for him. Her adoration was plain enough. But the depths of it—how she compared him to a majestic winged corrut and sometimes fancied herself his lady—escaped him. When she sat straighter in her saddle, adopting what she took to be a more adult pose, Dekür did not notice and would not have recognized the pose for what it was had he chanced to glance her way. He had no notion that his daughter found herself tongue-tied around him. He understood more of what her brother, Tynec, thought and felt, and Tynec was only eight—a boy who still played swordfight with sticks and walked with fantasy companions. Lewyn, at fourteen, was intelligent, with a mind for strategy, if often given to the most absurd flights of romantic fancy about life and the world. He loved her dearly, but there was

and always would be distance between them. She looked far too much like her mother.

Dekür thought of his own father, Ronnæm, whom he had just left back in the village of Ukobachia. At one time not so long ago Ronnæm would have denied vigorously the notion that he might one day live anywhere near—much less with—a village of Kobachs; but that was before Dekür had defied his parents and (his father would have said) all decency to marry a Kobach woman: Leyanna. But the old man’s bigotry had proven no match for Leyanna’s quiet determination. So successful were her efforts to erase his prejudices against the Kobachs that, when she died so young, it was Ronnæm who needed the most consolation, who’d locked himself away and wept for hours.

The love Dekür had for his father made him smile. The old man, for all his faults, had taught Dekür well. He wondered if he could pass as much governing wisdom to Tynec and Lewyn.

Perhaps when they returned to Atlarma he would consult a soothsayer. And with that decision, he closed his eyes and let his horse do all the thinking.

*****

As they rode, the ground rose on the right to grassy hillocks.

The trees on the left grew close to the road, the dirt track shadowed by their overhanging branches. Dekür’s horse shied. The king opened his eyes, raised his head.

The attacking soldiers, their clothing green and muddy brown, seemed to rise out of the hillside. They sprang before Dekür could shout a warning, sweeping down on the party like a flock of harpies, hurtling into the nearest riders, stabbing with the spikes on the tops of their helmets, impaling, killing many in that first instant.

Shouts of surprise and pain rang out from Dekür’s men. The attackers uttered no sound.

Horses fell, screaming, crushing their riders. Swords grated, drawn from scabbards, and the fight began.

Having no chance to draw his own sword, Dekür ducked low, took his attacker across his back, then reached around, grabbed the lip of the soldier’s helmet and flung the body around him. With both hands he twisted the helmet to break the soldier’s neck as he dropped him to the ground. Then he leaned out from his saddle, grabbing blindly for the reins of Lewyn’s horse. Missed them. Lewyn sat petrified with fear. He grabbed again, clutched her reins and pulled them free from her limp grasp. Beneath him, the soldier he had thrown off scrambled up. Dekür cursed the man’s strong neck and kicked out at the helmeted head, catching it in the visor; kicked again, knocking the soldier back against the flanks of Lewyn’s horse. The soldier grappled for his kicking foot and managed to lock fingers around his ankle. Dekür spurred his horse into action. It leaped forward, knocking down a second soldier. The reins of Lewyn’s horse passed over her horse’s head and then jerked against Dekür’s grasp, wrenching, nearly dislocating his arm and shredding the soft leather of his gloves. But he held on and her panicked horse took to the gallop behind him. The enemy soldier, still clinging to his ankle and stirrup, dragged along with them.

Both hands full, Dekür could not draw his sword.

Ahead of him, his two pointsmen fought wildly. The nearest one had taken a terrible gash in his shoulder from a spike. He fought with his sword uncomfortably balanced in his left hand. Absurdly, Dekür thought, “Have to teach them to fight with both hands.”

He charged the pointsman’s enemy and rode him down. But, glancing back, he saw the soldier spring up again like a trampled blade of grass, as if nothing extraordinary had happened.

Dekür’s guts went cold.

Lewyn screamed, “Father!” She had come out of her shock and had seen the soldier dragging along with them.

“Don’t worry about him. He can’t hold on forever!” But he was not so sure, and his ankle was on fire in the other’s viselike grip. “If we get separated,” he shouted to his daughter, “you hug to Gafrey’s mane and ride all the way back to Atlarma. Don’t stop!”

“Father—”

“Just do it!”

“I will! Oh, gods!”

He never heard her speak another word.

The air around him began to sparkle and everything seemed to slow down. Dekür tried to kick his horse, but his legs moved sluggishly, as though through syrup. The sparkling lights dizzied him with their bobbing.

And then his horse was gone and his left hand was empty, and Lewyn and Gafrey had vanished. He fell slowly, slowly to the ground, felt his ankle sharply twist. He cried out at the pain. The enemy soldier had not disappeared.

Dekür landed on his face, dirt in his mouth and eyes, the air punched from his lungs. He choked, spat. The grip on his ankle relaxed. He knew what that meant and rolled over quickly.

The soldier, standing, pulled a bone dagger from his belt, and leaped. Dekür shot his arms straight up, caught the other’s wrists and tossed him to one side, then scrambled to his feet. His ankle buckled, but he forced himself to stay upright, fighting off the clench of nausea.

He pulled out his sword and struck at the rising soldier, sweeping the blade in an arc beneath the soldier’s helmet. The severed head flipped up bloodlessly and bounced on the ground. The body dropped at his feet. Then it exploded. Dekür raised his arm in protection as bits of the body spattered against him in a blast of wind. He expected blood and entrails. What hit him were twigs and thorns and tightly wound sprigs of long grass.

He stared agape. All that remained of the infernal soldier was the helmet. He limped to it, prodded it with the tip of his sword. The helmet rolled over and stopped against a stone. Empty. No head, no body, a thing of dry grass; a straw man.

Dekür wiped the dirt from his face. He looked back down the road. A few of the straw men had broken away from the fighting and were now walking purposefully toward him. He saw only two of his own men still standing. Even as he watched, one of them took a blade in the ribs and fell.

Dekür cried out: “Lewyn!”

Far away in the forest, he thought he heard a distant echo his name. “Lewyn,” he said and started off into the trees. He tried to run, but his ankle would not hold him and he fell into bushes that jabbed and gashed his face. Stumbling defiantly up, he hobbled on into the deeper gloom, making a path where none had been.

He called his daughter’s name again, was certain this time that he heard her reply, and moved ahead as quickly as he could.

After a while, he leaned against a tree to rest his ankle and his frayed wits. Far behind him, something moved cumbrously along the path he had made. The infernal creatures would not allow him to rest. Dekür hesitated a moment, tears of pain squeezing from his eyes, and then headed deeper into the forest, grabbing onto low branches and small trees for support.

As he moved on, the plants and trees around him began to change. It was a subtle change at first, and in his agony he failed to notice. Then he grabbed something soft and liquid on a branch, and all at once he realized. He stopped.

The plants had acquired an oily sheen. The trees were bent, deformed; their leaves were no longer green but red and maroon, and hung as if in heavy fatigue. He smelled a sulfurous rot on the air and thought to turn back then, but behind him came the crashing through the brush of men or things like men, much closer now than before, though he couldn’t see them yet. Ahead, somewhere, was his daughter. He moved forward.

His ankle had swelled. With each step now, it seemed to grate inside his boot. But there was no time to stop and bind it. He moved on with his teeth clenched, his stomach folding and threatening to rise.

The forest threw off sharp, acrid odors that made his eyes water. The inside of his nose burned. His throat felt raw. Wiping at his eyes, Dekür paused, blinking, to look ahead. There, where a gap showed between the trees, the forest appeared to have turned black.

He moved toward this area cautiously, his sword at the ready. As he closed on the blackness; he saw that it was a wall, an enormous black wall. He touched it: cold, the rough stones wet. Dekür looked up. The wall ended smoothly above the trees—no battlements or windows graced its heights.