Lyttelton's Britain (2 page)

Read Lyttelton's Britain Online

Authors: Iain Pattinson

I

T WAS

1991. I’d only completed a few months as a trainee producer at the BBC when I was summoned to the office of HLER (that’s BBC acronym for Head of Light Entertainment Radio). ‘The producer of

I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue

will be moving on to other things,’ said HLER. ‘We think you’d make a good replacement’. Up till then I’d barely produced any programmes at all and must have looked a little shaken. ‘Don’t worry, you’ll be fine,’ said HLER. ‘Just remember to laugh at all their jokes’.

The standard procedure in BBC Radio Entertainment at the time was for new producers to serve an apprenticeship on a show before attempting to operate it themselves. Since the next series of

Clue

wasn’t due to start for a couple of weeks, I just sat in my office and awaited instruction. After a week or so had passed, I paid a visit to Janet Staplehurst (the programme’s long-serving production assistant) to ask for news of the producer’s imminent return from the Edinburgh Fringe. ‘His show’s going down rather better than expected,’ said Janet. ‘He’s decided to stay up there. You’ll have to produce the series yourself.’ My mind raced and I felt slightly sick. The ever-efficient Janet was reassuring: ‘Don’t worry. The studio’s booked – and the team.’ I felt heartened. ‘And who writes the links for Humphrey Lyttelton?’ I asked. ‘You do,’ she replied.

Even less impressive than my track record as a producer then were my credits as a broadcast scriptwriter. Up till 1991 – nothing. Not a scrap. When the day of my first recording as producer of

I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue

arrived, and I finally introduced myself to its seventy-year-old chairman Humphrey Lyttelton, my face was still aching from an afternoon of sycophantic forced merriment in the company of the rest of the

Clue

team. It was with not a little trepidation that I handed Humph the script for the show. I was expecting at the very least a critical eye to be cast over my efforts, before various jokes were cut out or hastily re-written. Instead, he thanked me politely and didn’t give the script a second glance. When the recording started my heart was in my mouth. Then, as the show’s opening signature tune faded into audience applause, suddenly and quite palpably, I began to understand the genius of the man. With effortless timing, natural ease and unforced charm he took my fledgling script and made it fly. Not only was he able to elicit gales of laughter where the best I’d hoped for was the occasional flurry, but, most remarkably, he was able to conjure audience hilarity from a simple pause, an inflection, a sigh, a shift of tone, even from silence. It was a complete and towering tour de force and in minutes my mood changed from near hyperventilating panic to the most indescribable joy. That night I was seized with one single-minded determination: to ensure Humphrey Lyttelton’s scripts were as good as they could possibly be.

Some months later, during a brief stint producing

The News Quiz

, I found myself working with a writer called Iain Pattinson. Iain was unlike most of the young, faintly unkempt, university-educated writers who filtered their way into the Radio

Entertainment department in the hope of a commission. After a short and unexceptional education in Sidcup, Iain had worked as a market stall holder, insurance broker and marketing executive in the oil industry, before taking early retirement to pursue a dream of writing comedy. Despite his relatively advanced years, a fizzing resentment at the apparent preferment of his Oxbridge-educated peers seemed to lend him a certain youthful vigour. Unlike the department’s other writers, Iain was not only ‘life educated’, he was also financially secure. Quite early in his new career as a writer, he was offered a job on Channel 4’s all-new

Clive Anderson Talks Back

, a job offer that any of his colleagues would have jumped at without hesitation. Ian took one look at the fee and declined, with the words: ‘That’s less than I pay my gardener’. I liked that. And I realised also that the wonderful material he was writing for

The News Quiz

could be done infinitely more justice were it delivered by Humphrey Lyttelton.

So it was that I bequeathed to Iain the role of Humphrey’s link writer, in turn heralding the most significant writer/performer relationship in Radio Comedy since Galton & Simpson began writing for Tony Hancock. For sixteen years Iain has written for Humphrey some of the most unfalteringly brilliant and enduring comic lines ever heard on a British wireless, lines which have in turn been delivered with an incomparable skill, style and charm.

Having attempted the job myself, I was well placed to appreciate the difficulty Iain faced, week after week, trying to come up with an amusing introduction to each edition of the programme. Writers on panel shows that draw their material from specific areas such as news, sport or music, immediately have a peg on which to hang their opening material. The problem Iain faced

was that

I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue

draws its inspiration from no single theme. However, we swiftly discovered that by taking the show on the road, not only did we lose our London audience of elderly bag ladies, foreign tourists and assorted oddballs seeking shelter from the cold, but most significantly, we gained a location around which to frame Iain’s introductory lines. At first these introductions were no more than a couple of paragraphs, but they soon developed into extended comic histories of the place visited, hugely appreciated by the local theatre audience and one of the most popular elements of the programme as a whole.

Iain’s great skill was not only to write wonderfully funny material, it was also his complete understanding of the character of ‘Chairman Humph’, the unwilling, aristocratic, sometimes irritable, frequently baffled, occasionally louche, often semi-comatose chairman of Britain’s most popular radio panel game. Over the years Iain’s opening material for

I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Clue

has evolved into the almost comprehensive UK gazetteer you have in your hands today. Every page of it seems to resonate with the character and personality of Chairman Humph. It serves as both a reminder of, and tribute to, one of the most brilliant, unique and best-loved broadcasting talents I ever expect to see in my lifetime.

Jon Naismith

LYTTELTON’S BRITAIN

LYTTELTON’S BRITAIN  ENGLAND

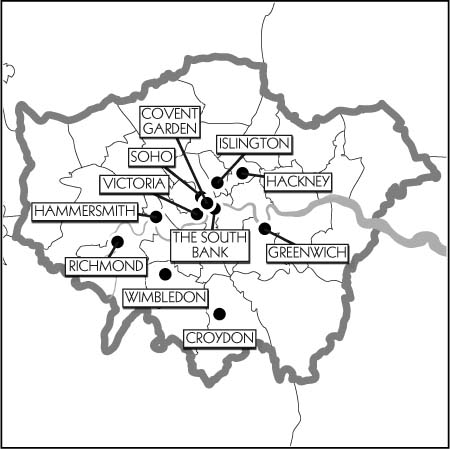

ENGLANDLONDON

G

REENWICH

is a London borough which rightly prides itself in a rich history spanning many centuries of Royal association. In 1415, Henry V landed in Greenwich after his return from the Battle of Agincourt, when the vastly superior French horsemen were comprehensively routed by our English archers. But then ten minutes of Linda Snell is enough to terrify anyone.

Henry’s military success thus secured France as a market for fine British meat products, and to teach them a lesson, he decreed that export cattle should be fed on diseased sheep carcasses, in the certain knowledge the French would never notice.

Elizabeth I came to Greenwich in 1580 to knight Francis Drake in reward for his round the world voyage. Townsfolk flocked to witness the sight of Good Queen Bess taking up a large sword to perform his circumnavigation ceremony. This was before English spellings were standardised, and as the result of a slight but painful misunderstanding, the words ‘Arise, Sir Francis’ were entirely wasted on him.

In the 17th Century, architect Christopher Wren did much to set the style of Greenwich when his colonnaded, Neo-Renaissance Royal Naval College was commissioned. However, this was only after his original design, of a huge, upside-down Tupperware bowl held up by string attached to big sticks, was rejected on the grounds the town wanted something visitors might bother to come and see.

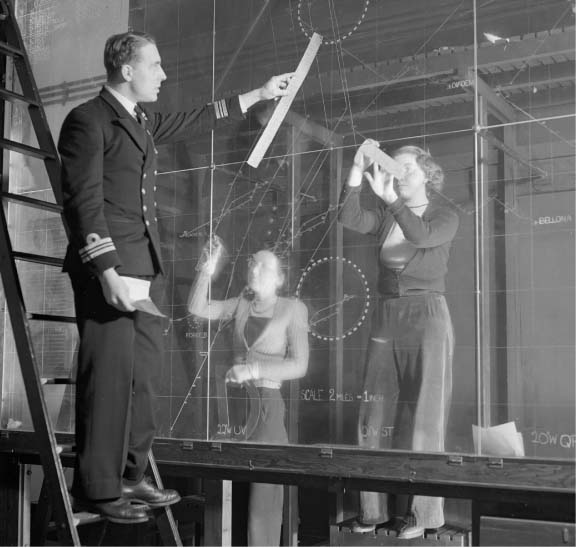

Royal Naval College, Greenwich, 1948. (The law was later changed, making it illegal to keep women in large aquariums)

Greenwich is also famous for its long associations with literature. Christopher Marlowe frequented local taverns and was supposedly killed in one during a brawl with friends over the bill for dinner. The theory that Marlowe didn’t actually die but

assumed a new identity as William Shakespeare is supported by the line from

Twelfth Night

: ‘If music be the food of love, play on, but there’s no way I had a prawn cocktail starter.’

Local residents have included the intellectual and pioneering landscape gardener John Evelyn, who is mentioned by his neighbour Samuel Pepys in the diaries which he wrote in Greenwich in his own special code. As a result, Evelyn has a local pub named after him: ‘The Dot, Dot, Dash, Dash, and Bucket’.

The same century saw the founding of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich Park. The finely crafted lenses of its Newtonian telescope gave an unprecedented view of the Northern skies right up until the 1980s, when it had to be moved after someone built a bloody great office block in the way at Canary Wharf.