Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (16 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Clemenceau could not be accused of hypocrisy. His forty-one-year-old son Michel, a lieutenant in the Fourth Army, had very nearly given his own life a fortnight into the conflict when he was shot by a German lancer. Showing some of his father’s famous dueling spirit, he managed to kill his antagonist before passing out. Still, Monet may not have wished to entertain arguments about the necessity of children laying down their lives for la Patrie. His own son Michel had finally been accepted into the army, in part because recruiting restrictions dropped following the deaths in battle of almost three hundred thousand French soldiers. How much Clemenceau discussed politics or the war with Monet is uncertain. Giverny was his sanctuary: he valued Monet’s company, among other reasons, precisely because politics held so little interest for him.

Clemenceau was a sparkling conversationalist whose every witticism his acquaintances admiringly recorded in their diaries. Monet, on the other hand, was a man of few words. “Don’t ask me anything,” he once warned a visitor. “Don’t try to make me talk. I have nothing interesting to say.”

8

As Sacha Guitry observed: “Claude Monet did not have what is commonly called conversation. To the most important questions asked him on art, he would answer by a ‘Yes’ or a ‘No’...You spoke to him: he listened to you.”

9

Yes or no answers were, in fact, more than some people got out of Monet. A bystander once overheard him replying to friendly questions from Geffroy with a rough growl: “Rrrou...Rrou...Rrou...”

10

And he was laconically noncommittal even with Clemenceau. “One may have been the most intimate friend of Monet,” he remarked to Guitry, “without ever having known the man’s thoughts.”

11

Monet’s friends never mistook his taciturn demeanor for a lack of intelligence. Guests moving from his dining room for the postprandial coffee in his living room passed through the “Salon Bleu,” his eclectic and well-stocked library. According to Geffroy, Monet had loved books ever since he first arrived in Paris and met many writers and intellectuals at the Brasserie des Martyrs.

12

When he painted Monet’s portrait in 1874, Renoir showed him not at the easel but, rather, hunched intently over a book, smoking a pipe and looking decidedly professorial. At Giverny, in his more sedate maturity, Monet used to read aloud in the evening as Alice sat beside him in the Salon Bleu, sewing and listening. Among his favorites, apart from Mirbeau and Geffroy, were authors such as Flaubert, Zola, Ibsen, Hardy, and Tolstoy. He also read the classics: Aristophanes, Tacitus, and Dante. He worked his way through nonfiction too: Montaigne, Hippolyte Taine, Jules Michelet’s

History of France

, the

Memoirs

of Saint-Simon, the journal of Delacroix. Monet did not appear in the pages of the latter, although in his youth he used to spy on Delacroix’s studio from the window of a neighboring building, hoping for a glimpse of the painter at work—thus demonstrating the same avid interest in the master that, decades later, others passing through Giverny would show in him.

MONET’S LITERARY INTERESTS,

as well as the promise of a good meal, took him to Paris for a final time in 1914. The week before Christmas he attended the monthly luncheon of the Académie Goncourt, a literary society (more properly known as the Société littéraire des Goncourt) that had been founded with a legacy from Edmond de Goncourt. Geffroy and Mirbeau had been founder members of the Académie Goncourt in 1900, with Geffroy serving as president since 1912. It was a continuation, of sorts, of Mirbeau’s Bons Cosaques (who broke bread together for the last time in 1888): the membership was broadly the same, as was the enthusiasm for both literature and food.

The ten members of the Académie Goncourt, known as Les Dix, met for lunch on the first Tuesday of each month, initially at the Grand Hôtel, then later at the Café de Paris. For the past few months, they

had been gathering in a wood-paneled private dining room, the “Salon Louis XVI” (soon to be known as the “Salon Goncourt”), in the restaurant Drouant, a specialty seafood establishment near the Opéra much frequented by Clemenceau and other journalists. “They discuss various topics during the meal,” a newspaper reported, “and then, as dessert is served, they begin to study the literary production of the year.”

13

The upshot of these earnest deliberations over the

pêche Melba

was, each December since 1903, a five-thousand-franc literary prize: the Prix Goncourt.

Although not officially one of Les Dix, Monet was a regular fixture at the monthly Goncourt lunches. They were one of the few things that could lure him to Paris, the attraction being good food and good conversation in the company of his boon companions.

Monet’s presence as a painter among a group of writers was not as incongruous as it might have seemed. He had long been on friendly terms with many writers besides Mirbeau and Geffroy. At the Bons Cosaques dinners in the 1880s he had met writers such as Henri Lavedan, Paul Hervieu, and J.-H. Rosny the Elder, whom he called “men of heart and talent.”

14

He often seemed more comfortable with writers, in fact, than with painters. He had been close friends with Stéphane Mallarmé before the poet’s death in 1898. One of his proudest possessions—on prominent display in his studio, among photographs of friends—was the yellowed envelope on which Mallarmé, a regular visitor to Giverny, had composed his address in verse:

Monsieur Monet que, l’hiver ni

L’été, sa vision ne leurre

,

Habite, en peignant, Giverny

,

Sis auprès de Vernon, dans l’Eure

.

(Monsieur Monet who, neither winter nor

Summer his vision can blur

,

Lives, painting, at Giverny

,

Found at Vernon, in the l’Eure.)

The letter found its recipient, with Monet later marveling that the envelope had not been stolen by an “intelligent mailman.”

15

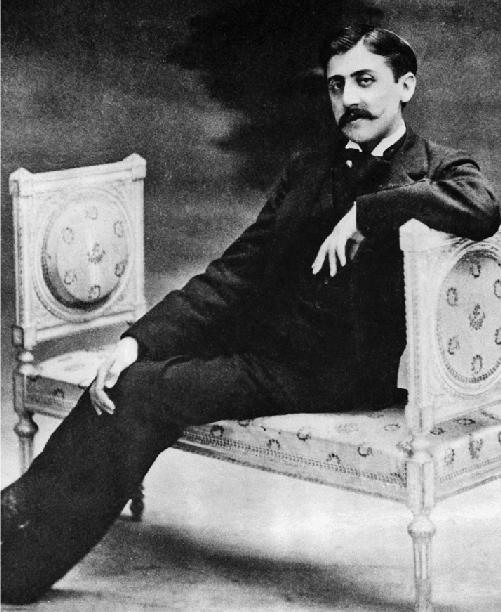

Monet was a painter uniquely admired by novelists, most enthusiastically, perhaps, by Marcel Proust, an unabashed Monet hero worshipper and would-be visitor to Giverny. Proust even hoped to write a book about Monet’s garden.

16

However, the two men had never met. Visits arranged by mutual friends had failed to come off—possibly for the best, since the haze of pollens in Monet’s garden might have distressed the severely asthmatic Proust, who was obliged to ask his visitors to forgo flowers in their buttonholes.

Proust had therefore to content himself with making pilgrimages to the places in Normandy painted by Monet “as though these were shrines.”

17

He mentioned Monet many times in his writings: fifteen times in his notebooks, twenty-four times in his unfinished novel

Jean Santeuil

, a dozen times in

Contre Sainte-Beuve

, and at numerous points in his essays and letters. Monet’s name was also destined to appear ten times in Proust’s magnum opus,

Remembrance of Things Past

, the first volume of which,

Swann’s Way

, had been published in December 1913.

Something of Monet’s appeal for Proust was summed up in 1909 by the novelist and playwright Henri Ghéon, who outlined the difference between Monet and other painters, such as Degas and Cézanne: “They paint in space, he—if I may say—paints in time.”

18

Monet was interested, like a novelist, in depicting and exploring the effects of time. By showing the natural world through different seasons and at all times of the day, his serial paintings of wheat stacks, for example, reveal how the viewer’s impressions no less than the objects themselves are transformed by time’s workings, giving a temporal perspective on people and places. The experience of these spaces and places, Monet believed, was affected by the particular moment in which we encounter them. Proust expressed the same philosophy in the last lines of

Swann’s Way

when he wrote that “the places we have known do not belong only to the world of space” but are, rather, “contiguous impressions” experienced at particular points in our lives. Monet’s paintings constituted a series of these contiguous impressions—of objects and spaces dissolving into time such that, as Proust wrote, the

“houses, roads, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.”

Marcel Proust

Swann’s Way

was eligible for the Prix Goncourt in 1914. There is no evidence that Monet ever read Proust or that Proust’s admiration for Monet was in any way reciprocated. Monet did, however, act as an advocate for other writers. Besides tucking into the oysters and noisettes of lamb at the Goncourt dinners, he also participated informally in the decision making, occasionally trying to influence jurors. One year earlier the novelist Lucien Descaves, a member of Les Dix, had received a letter from Monet in which the painter frankly admitted he might be sticking his nose in where it did not belong—but “no matter,” he shrugged, before urging Descaves to cast his vote for Léon Werth’s novel

La Maison blanche

. Monet’s advocacy of the novel had less to do with the novel’s undoubted merits than the fact that Werth, a close friend of Mirbeau, had been serving as the ailing author’s amanuensis, helping him to complete his novel

Dingo

. Monet explained to Descaves that Werth was a “man of real talent,” that the prize would do him “a great good” and that his victory—and here was the nub of the matter—would “cheer poor Mirbeau.”

19

Werth did not win the prize that year despite Monet’s backing. Nor did the novel that posterity would have garlanded, Alain-Fournier’s

Le Grand Meaulnes

. Tragically, Alain-Fournier had been killed in battle in September, aged only twenty-seven, leaving his second novel unfinished. His death, announced in

Le Figaro

only a few weeks earlier,

20

must have hung heavily over the luncheon festivities that December afternoon, all the more so since Werth, at that moment, was in uniform at the front. The purpose of the meeting was, in fact, to decide whether or not to award the

prize at all in 1914, given that many works announced for publication and eligible for consideration were still at the printers because of the mobilization of authors, editors, and publishers. In the end, Proust and all other hopefuls would have to wait: Les Dix decided against awarding the prize, announcing that, instead, two awards would be made in 1915.

21

Much hope certainly rested on 1915. In August the Kaiser had assured his troops that they would be back home “before the leaves have fallen from the trees,” while the chief of the general staff, Helmuth von Moltke, predicted that the war would be over by Christmas, a sentiment echoed by the British prime minister, Herbert Asquith, and quickly adopted as a popular saying in the first months of the war.

22

But there were, as the holidays arrived, no signs of peace breaking out. Christmas Day was observed, according to the official communiqués, by vigorous German attacks at Tête-de-Faux in the Vosges, north of Lens, and along the Aisne. “In the distance,” wrote a French journalist in Alsace at sunset on Christmas Day, “the sound of cannons and machine guns still reaches us.”

23

Only a heavy fog at last halted operations.

THREE DAYS AFTER

Christmas, Monet wrote to a painter friend deploring the “terrible year” and expressing his hopes for a better state of affairs in 1915. He explained that, with Michel about to be mobilized, he and Blanche would soon be alone in the house. “I must admit,” he wrote to Geneviève Hoschedé, “that I feel very hopeless and sad at this depressing end to the year, and fearful of the future.”

24

By early 1915, word of Monet’s new project had begun to circulate. In January he received a letter from a friend in Paris, Raymond Koechlin. The fifty-four-year-old Koechlin was the sort of wealthy and cultured patron—albeit Protestant rather than Jewish—that Clemenceau originally had in mind for Monet’s decorations. President of the Society of Friends of the Louvre and former editor of the highbrow

Journal des débats politiques et littéraires

, Koechlin was independently wealthy thanks to his father, an Alsatian textile manufacturer who relocated to Paris after the Franco-Prussian War and ultimately became mayor of the 8th arrondissement. Koechlin, a widower, filled his apartment overlooking

the Seine on the Île Saint-Louis with Japanese prints, Muslim ceramics, Chinese pottery, and also modern paintings: Delacroix, Renoir, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and of course Monet, whom he hailed as a fellow “Japanese fanatic.”

25