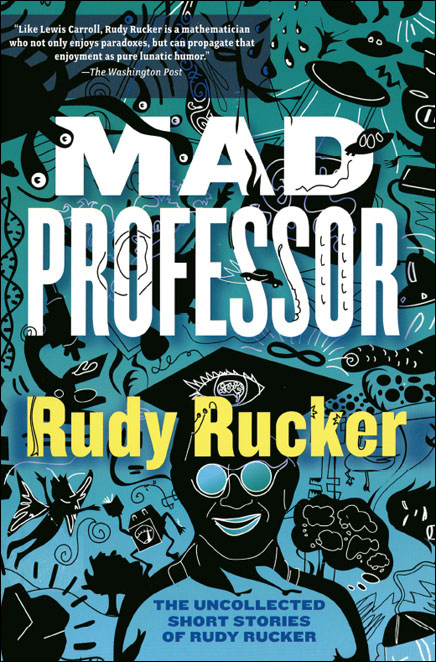

Mad Professor

Authors: Rudy Rucker

PROFESSOR

MAD

PROFESSOR

The Uncollected Short Stories of

RUDY RUCKER

Â

THUNDER'S MOUTH PRESS

NEW YORK

M

AD

P

ROFESSOR

The Uncollected Short Stories of Rudy Rucker

Published by

Thunder's Mouth Press

An imprint of Avalon Publishing Group, Inc.

245 West 17th Street, 11th floor

New York, NY 10011

Copyright © 2007 by Rudy Rucker

First printing, 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-10: 1-56025-974-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-56025-974-9

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Book design by Maria E. Torres

Distributed by Publishers Group West

Â

Â

Â

Â

For Robert Sheckley, 1928â2005

The premise could be seen wavering, there were repercussions of a rhetorical nature, and the author could be glimpsed, a ghostly figure of unbelievable beauty and intelligence, trying desperately, despite his many personal problems, to put things together again.

âRobert Sheckley,

Minotaur Maze

2+2=5 (

Written with Terry Bisson

)

Elves of the Subdimensions (

Written with Paul Di Filippo

)

The Men in the Back Room at the Country Club

Guadalupe and Hieronymus Bosch

Six Thought Experiments Concerning the Nature of Computation

Jenna and Me (

Written with Rudy Rucker Jr.

)

The Use of the Ellipse the Catalog the Meter & the Vibrating Plane

Junk DNA (

Written with Bruce Sterling

)

Pockets (

Written with John Shirley

)

OF

course I'm not a mad professorâeverything I write and do is perfectly logical! Come right this way, step into my laboratory, and you'll see for yourself. Careful not to touch that leverâ

whoops,

you've turned on a lecture.

I might characterize my fiction by four qualities:

⢠Thought experiments

⢠Power-chords

⢠Gnarliness

⢠Wit

The notion of fictional

thought experiments

was made popular by no less a mad professor than Albert Einstein, who fueled his science speculations with

Gedankenexperimenten.

Thought experiments are a very powerful technique of philosophical investigation. In practice, it's intractably difficult to visualize the side effects of new

technological developments. In order to tease out the subtler consequences of current trends, a complex fictional simulation is necessary; inspired narration is a more powerful tool than logical analysis. If I want to imagine, for instance, what our world would be like if ordinary objects were conscious, then the best way to make progress is to fictionally simulate a person discovering this.

The kinds of thought experiments I enjoy are different in intent and in execution from merely futurological investigations. I'm not necessarily trying to make useful predictions that businessmen can use. I'm more interested in exploring the human condition, with literary power chord standing in for archetypal psychic forces.

+ Â + Â +

When I speak of

power chords

in the context of fantastic literature, I'm talking about certain classic tropes that have the visceral punch of heavy musical riffs: blaster guns, spaceships, time machines, aliens, telepathy, flying saucers, warped space, faster-than-light travel, immersive virtual reality, clones, robots, teleportation, alien-controlled pod people, endless shrinking, the shattering of planet Earth, intelligent goo, antigravity, starships, ecodisaster, pleasure-center zappers, alternate universes, nanomachines, mind viruses, higher dimensions, a cosmic computation that generates our reality, and, of course, the attack of the giant ants.

When I use a power chord, I try to do something fresh with the trope, perhaps placing it into an unfamiliar context, perhaps describing it more intensely than usual, or perhaps using it for a novel thought experiment. I like it when my material takes on a life of its own. This leads to what I call the gnarly zone.

+ Â + Â +

I discuss my concept of

gnarl

at length in my nonfiction tome,

The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul: What Gnarly Computation Taught Me about Ultimate Reality, the Meaning of Life, and How to Be Happy

(Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005).

In short, a gnarly process is complex and unpredictable without being random. If a story hews to some very familiar pattern, it feels stale. But if absolutely anything can happen, a story becomes as unengaging as someone else's dream. The gnarly zone is lies at the interface between logic and fantasy.

I see my tales as simulated worlds in which the characters and tropes and social situations bounce off each other like eddies in a turbulent wake, like gliders in a cellular automaton graphic, like vines twisting around each other in a jungle. When I write, I like to be surprised.

William Burroughs was an ascended master of the gnarl. He believed in having his work take on an autonomous life to the point of becoming a world that the author inhabits. “The writer has been there or he can't write about it. . . . [Writers] are trying to create a universe in which they have lived or where they would like to live. To write it, they must go there and submit to conditions that they might not have bargained for.” (From “Remembering Jack Kerouac” in

The Adding Machine: Selected Essays,

Seaver Books 1986.)

+ Â + Â +

And now a few words about

wit

. Robert Sheckley, to whose memory

Mad Professor

is dedicated, was a supremely witty writer. Over the years I got to spend a few golden hours in Sheckley's presence. And I think it's safe to say that wit, rather than mere humor, characterizes his work.

Wit involves describing the world as it actually is. You experience a release of tension when you notice a glitch. Something was off-kilter, and now you see what it was. The elephant in the living room has been named. The evil spirit has been incanted. Perceiving an incongruity in our supposedly smooth-running society provokes a shock of recognition and a concomitant burst of laughter. Wit is a critical-satirical process that can be more serious than the “humorous” label suggests.

In this vein, Sheckley writes: “Good fiction is never preachy. It tells its truth only by inference and analogy. It uses the specific detail as its building block rather than the vague generalization. In my case it's usually humorousâno mistaking my stuff for the Platform Talk of the 6th Patriarch. But I do not try to be funny, I merely write as I write. . . . In the meantime I trust the voice I can never loseâmy own . . . enjoying writing my story rather than looking forward to its completion.” (From “Amsterdam Diary” in

Semiotext[e] SF,

Autonomedia 1997.)

+ Â + Â +

The “mad professor” theme is itself a classic power chord.

One way to think of the trope is as a dialectic triad: the thesis of the dry professor and the antithesis of the unpredictable artist are synthesized into the mad professorâlike Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde sharing a single body.

A different way to think of it is that being mad is actually part of being a professor, and not any kind of aberration. Professors, after all, have their heads in the clouds. They don't see things like regular people do.

In the famous allegory of the cave in Book VII of

The Republic,

Plato describes a race of humans who spend their lives staring at

shadows on the wall of a cave. From time to time some of them escape from the cave into the higher world. Having experienced the light of the true Sun, when they return to the prison of the cave their eyes are a bit slow in catching the subtleties of the shadow-play that ordinary men and women deem to be the entire real worldâthey're like absent-minded professors.

“And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring the shadows with the prisoners who had never moved out of the den, while his sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady . . . would he not be ridiculous? Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending; and if any one tried to loose another and lead him up to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.”

Further shadings in the mad professor archetype can be found by distinguishing it from the mad scientist. What's the difference? Professors tutor and counsel their students, they lecture and teach, they publish books and papers. They're social. It's not enough for a mad professor to gloat over the secret of reality in a dungeon lab as a mad scientist might. No, the mad professor is driven to write up what he or she saw, and to try and make everyone understand it. Another difference would be that the professors, who are less goal-oriented than the scientists, love erudition for its own sake, and affect a high literary style studded with quotes from timeless intellectual figures such as William Burroughs, Robert Sheckley, and Plato.

+ Â + Â +

I'm certainly a professor. I started my academic career as a calculus section tutor in graduate school forty years ago. I worked

as a professor of mathematics for about twenty years, and spent the following twenty as a professor of computer science. Two years ago I retired and became an emeritus professor, which means I get to stay home all the time.

I admit to being contrary, unpredictable, and idiosyncratic. But mad? Of course not. As my character Bela Kis puts it in my recent novel

Mathematicians in Love

(Tor Books, 2006): “Crazy means illogical. I'm logical. Therefore I'm not crazy. Note that a system can be at the same time logical and unpredictable.”