Maelstrom

by ARTHUR C. CLARKE

It must have been in 1937 or ’38, when I was Treasurer of the five-year-old British Interplanetary Society (annual budget to start the conquest of space, about $200), that the BIS was sent a book with a rather odd title, by an author with an even odder name. “Akkad Pseudoman’s”

Zero to Eighty

(Princeton: Scientific Publishing Company, 1937) must now be quite a rarity: I am indebted to my old friend Frederick I. Ordway III (responsible for the technical designs in

2001: A Space Odyssey)

for the fine copy I possess.

He was not, of course, really Mr. Pseudoman, as the preface made clear. This was signed “E. F. Northrup,” and explained that the book had been written to show that the Moon may be reached by means of known technologies, without “invoking any

imaginary

physical features or laws of nature.”

Dr. E. F. Northrup was a distinguished electrical engineer, and the inventor of the induction furnace which bears his name. His novel, which is obviously a wish-fulfillment fantasy, describes a journey to the Moon (and around it) in a vehicle fired from the earth by a giant gun, as in Jules Verne’s classic

From the Earth to the Moon

. Northrup, however, tried to avoid the obvious flaws in Verne’s

naive

proposal, which would have quickly converted Ardan

et al.

into small blobs of protoplasm inside a sphere of molten metal. Northrup used an electric gun,

two hundred kilometers

long, most of it horizontal but with the final section curving up Mount Popocatepetl, so that the projectile would be at an altitude of more than five kilometers when it reached the required escape velocity of 11.2 kilometers per second. In this way, air-resistance losses would be minimized, but a small amount of rocket power would be available for any necessary corrections.

Well–it makes more sense than Verne’s Moongun, but not by much. Even with 200 kilometers of launch track, the unfortunate passengers would have to withstand 30 gees for more than half a minute. And the cost of the magnets, power stations, transmission lines, etc. would run into billions; rockets would be cheaper, as well as far more practical.

I am sure that “Akkad Pseudoman” would have been surprised–and delighted–to know that men first circled the Moon aboard Apollo 8 at Christmas 1969; the date he gave in his novel was June 28, 1961. Incidentally, he was not the first to propose this scheme: the Winter, 1930

Science Wonder Quarterly

has a beautiful Frank R. Paul illustration of a line of giant electromagnets, shooting a spaceship up a mountainside. It could very well have served as the frontispiece of

Zero to Eighty

.

A few years after reading Dr. Northrup’s book (which is still full of interesting ideas, including a remarkably sympathetic–especially for the time–treatment of Russian technology) it occurred to me that he had made one slight mistake. He had put his electric launcher on the wrong world; it made no sense on Earth–but was ideal for the Moon.

First: there’s no atmosphere to heat up the vehicle or destroy its momentum, so the whole launching track can be laid out horizontally. Once it’s given escape velocity, the payload will slowly rise up from the surface of the Moon and head out into space.

Second: lunar escape velocity is only one-fifth of Earth’s, and can therefore be attained with a correspondingly shorter launch track–and a

twenty-fifth

of the energy. When the time comes to export goods from the Moon, this will be the way to do it. Although I was thinking of inanimate payloads, and launchers only a few kilometers long, suitably protected human passengers could be handled by larger systems, if there were ever enough traffic to justify them.

I wrote up this idea, with the necessary calculations, in a paper titled “Electromagnetic Launching as a Major Contribution to Space-Flight,” which was duly published in the

Journal of the British Interplanetary Society

(November, 1950); it may be more conveniently located in my

Ascent to Orbit: A Scientific Autobiography

(Wiley, 1984). And because a good idea should be exploited in every possible way, I used it in fiction on two occasions: in the chapter “The Shot from the Moon” (

Islands in the Sky

, 1952) and in the short story “Maelstrom II” (Playboy, April 1965, reprinted in

The Wind from the Sun

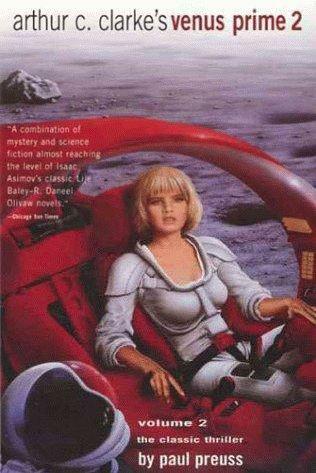

, 1972). This is the tale which Paul Preuss has ingeniously worked into

Venus Prime

, Volume 2.

Some twenty years after the publication of “Electromagnetic Launching” by the BIS, the concept was taken much further by Gerald O’Neill, who made it a key element of his “space colonization” projects (see

The High Frontier

, 1977; Gerry O’Neill is justifiably annoyed by the Star Warriors’ preemption of his title.) He showed that the large space habitats he envisaged could be most economically constructed from materials mined and prefabricated on the Moon, and then shot into orbit by electromagnetic catapults to which he gave the name “mass drivers.” (I’ve challenged him to produce

any

propulsion device that doesn’t fit this description.)

The other scientific element in “Maelstrom II” has a much longer history; it’s the branch of celestial mechanics known as “perturbation theory.” I’ve been able to get considerable mileage out of it since my applied maths instructor, the cosmologist Dr. George C. McVittie, introduced me to the subject at Kings College, London, in the late ’40s. However, I’d come across it–without realizing–in dear old

Wonder Stories

almost two decades earlier. Here’s a challenge to you: spot the flaw in the following scenario. . . .

The first expedition has landed on Phobos, the inner moon of Mars. Gravity there is only about a thousandth of Earth’s, so the astronauts have a great time seeing how high they can jump. One of them overdoes it, and exceeds the tiny satellite’s escape velocity of about thirty kilometers an hour. He dwindles away into the sky, toward the mottled red Marscape; his companions realize that they’ll have to take off and catch him before he crashes into the planet only six thousand kilometers below.

A dramatic situation, which opens Lawrence Manning’s 1932 serial “The Wreck of the Asteroid.” Manning, one of the most thoughtful science fiction writers of the ’30s, was an early member of the American Rocket Society, and was very careful with his science. But this time, I’m afraid, he was talking nonsense: his high jumper would have been perfectly safe.

Look at his situation from the point of view of Mars. If he’s simply standing on Phobos, he’s orbiting the planet at almost eight thousand kilometers an hour (a Moon that close to its primary has to move pretty fast). As spacesuits are massive affairs, and not designed for athletic events, I doubt if the careless astronaut could achieve that critical thirty kilometers an hour. Even if he did, it would be less than a half-percent of the velocity he already has, relative to Mars. Whichever way he jumped, therefore, it will make virtually no difference to his existing situation; he’ll still be traveling in almost the same orbit as before. He’d recede a few kilometers away from Phobos–and be right back where he started, just one revolution later! (Of course, he could run out of oxygen in the meantime–the trip round Mars will take seven-and-a-half hours. So maybe his friends should go after him–at their leisure.)

This is perhaps the simplest example of “perturbation theory,” and I developed it a good deal further in “Jupiter V” (reprinted in

Reach for Tomorrow

, 1956). This story, incidentally, was based on what seemed a cute idea in the early ’50s. A decade earlier, LIFE Magazine had published space-artist Chesley Bonestell’s famous paintings of the outer planets. Wouldn’t it be nice, I thought, if sometime in the 21st century LIFE sent one of its photographers out there to bring back the real thing, and compare it with Chesley’s hundredyear-old visions?

Well, little did I imagine that, in 1976, the Voyager space-probe would do just this–and that, happily, Chesley would still be around to see the result. Many of his carefully researched paintings were right on target–though he couldn’t have anticipated such stunning surprises as the volcanoes of Io, or the multiplex rings of Saturn.

Much more recently, Perturbation Theory plays a key role in

2061: Odyssey Three;

and I won’t promise not to use it again one of these days. It gives all sorts of opportunities for springing surprises on the unsuspecting reader–

–Over to you, Paul Preuss!

Prologue

The wind was too thin to sustain a living thing but not too thin to carry the abrasive grit. The grit etched the rock and heaped the sand and carved the ice and the hard stone into arches and buttresses and buttes. The thin wind was a digger.

The hole it was digging now, in the sand beneath the ice, had a piece of metal in it. The metal was shiny and hard, not so hard that it had not been shattered–who knows when or how–but so hard the wind-borne grit could not mar its mirror surface.

Something else had etched the metal and dug channels in it. The channels were different from each other but all the same height and width and depth. They ran in straight lines. There were three dozen different kinds of them, but they repeated themselves in various sequences until the total number of them, etched in the metal, was a thousand and more.

“I’m sayin’ it’s too valuable. It’s one of a kind. You won’t get no money fer it, under the table or over.” This was about as private as you could get around here, in the poker nest under the pipe rack in the drill rig dome, where the booze and the dope were cached. The crew boss knew all about it; he didn’t give a squeak, as long as nobody showed up high on any company monitors. But you had to whisper in here. These damn domes carried sound from one side to the other just as good as a phone link, and you never knew who was standing over there listening in.

too

valuable.”

A week later, already four days behind schedule, the crew finally got the rig up and started to sink pipe. The sun went down in the red Martian sky, taking a pack of sundogs with it. Liam and Johnny were working the drillhead. They’d been hard at it for four hours and they were already down to permafrost when the pipe kicked–nobody ever did figure out how it happened, but it was no surprise, this was not a tight ship–but then Johnny really screwed up and it got away from him and the business end of the pipe blew a hole in the ice. Which normally would have resulted in maybe some people getting a quick ride back to the unemployment line in Labyrinth City, except right underneath them there was a big pocket of pressurized gas in the permafrost and it blew too, and the whole pipe rack went way, way up like a bundle of straws, and then all the straws came back down on Liam and John.