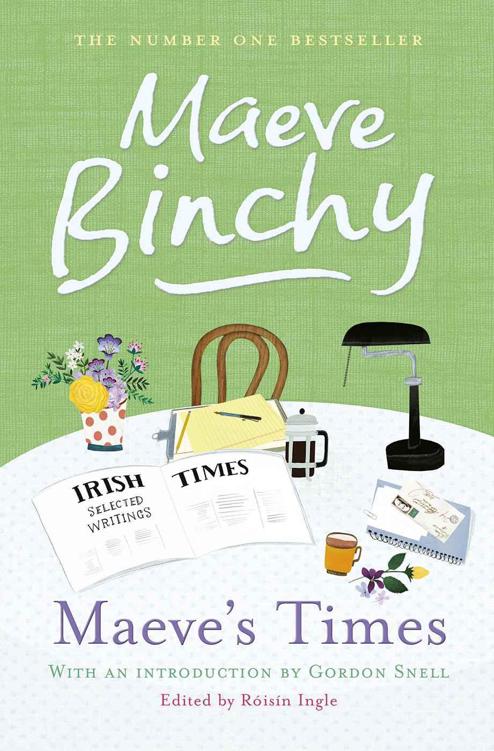

Maeve's Times

Authors: Maeve Binchy

Selected

Irish Times

Writings

Edited by Róisín Ingle

Note on Maeve Binchy and

The Irish Times

Thinking About Underwear Down Under

The World’s Greatest Lies About Women

Pageantry and Splendour at Westminster for the Royal Wedding

Keeping Faith with My Dear, Dear Dublin

The Couple Who Behaved Perfectly

Vanity of Vanity, All is Vanity

A Nice, Traditional, Normal Sort of Patrick’s Day

The Day We Nearly Wrote a Sex Book

Numbed Dover Waits for Lists of the Dead

The Right to Die in Your Own Home

Up in the Clouds with Charlie Haughey

Election Brings Life to an Ageing Society

Maeve’s Operation: The Whole Story

Keeping Cruise off the Roads is New Priority

One Eye on Bargains, One Eye on Alsatians

No Fags, No Food – It’s No Fun Being Fergie

It Was One of Those Custard Heart Days

The Man Who Set Up Office in the Ladies

A Royal Romance Spelling Danger from the Start

Even the Presidents Are Getting Younger

Casually Elegant Meets the Mob

Traveller’s Tales – The Call of the Check-In Desk

‘They’ve Gone and Dumped Portillo …’

Talking to Various Ships Passing in the Night

Staving Off the Senior Moments

Another World for the Price of a Cup of Coffee

Striking a Pose for My Country

Ten Things You Must Never Say to Anyone with Arthritis

What’s It Like to Have a House Full of Film Crew? Let Me Tell You All About It

Will and Kate Show Is Testament to Abiding Allure of the Royals

‘I Don’t Have Any Regrets About Any Roads I Didn’t Take …’ (in conversation with Joanne Hunt)

The Irish Times

Maeve Binchy was appointed Women’s Editor of

The Irish Times

in October, 1968. As a young teacher she had loved both her job and her holiday travels, and had been a favourite contributor since her first travel letter, sent in by her father, was published a few years earlier. On her appointment the then News Editor, the late Donal Foley, declared, ‘Won’t she be great crack to work with? And she’s a brilliant writer!’ Both proved true over a career which lasted the best part of fifty years.

Maeve wrote for and edited the daily ‘Women First’ page until 1973, when she transferred to the London office as a columnist, feature writer and reporter, balancing the day job with her rapidly growing career as a writer of fiction and drama. When Maeve resigned from the staff of

The Irish Times

in the 1980s, she retained her close association with the paper as a regular contributor. Maeve and her husband Gordon Snell moved back to Ireland in the early eighties.

F

rom her earliest childhood, Maeve loved stories – and wanted to be part of them. When her father started to read her some tale of two children wandering through a wood, she asked at once, ‘Where was I?’

He would say patiently, ‘You were sitting in a tree beside the path.’ And with Maeve happily located, the story could go on.

When she grew up and became a storyteller herself, she made her readers feel that, like little Maeve in the tree, they were on the scene, among the action and the characters. She did the same in her journalism, writing with on-the-spot directness of the people and events she met with.

It was her father’s enthusiasm that led to Maeve becoming a journalist in the first place. As a teacher she used her long holidays to travel all over the world, on cargo ships, cheap flights, trains and hitch-hiking. She worked in school and holiday camps, on a kibbutz, and as a tourist guide, in North America, the Middle East and Asia.

Her father sent some of her long, lively letters home to the newspapers, who published them as articles. That was the start of her career as a columnist – a job she kept doing happily even after she had become a celebrated novelist.

Whether she was observing a couple having an angry but icily polite disagreement, or feeling the panic – including her own – brought on by the trials of air travel, or watching the outlandish fantasies of the fashion industry, she had a unique eye and ear for the quirks, intensities and absurdities of human behaviour.

No wonder her readers were delighted with her – for she told it all with the eagerness and enthusiasm of someone who says, ‘Just wait till I tell you what happened ….’ and goes on to tell an enthralling and often hilarious tale.

She brought the same directness to her many serious reports for the paper – on the bombs in London and other cities, the capsized ferry disaster, and the savage war in Cyprus.

Maeve followed the advice she often gave to aspiring writers – to write as you speak. Her view of the world and the people in it was the same in her writing as it was in her life: she was compassionate and perceptive, she treated everyone with the same considerate interest, and her humour was uproarious but never sneering or cruel.

Her capacity for friendship seemed limitless, and hundreds of people from all over the world, who never knew her, have written to say that they thought of her as a friend.

I can almost hear her say, ‘That’s enough of that! You make me sound like some kind of saint!’ Indeed as a schoolgirl, sainthood was a role she considered aiming for, but decided against – partly on the grounds that it could involve martyrdom, but really because it just wasn’t her style.

We must all be glad she took on the roles she did, as teacher, writer, and friend to so many – and I above all feel specially lucky that we met, and spent so many happy and loving years together.

When I read these articles, stories and reports from

The Irish Times

, I hear her voice and feel she is back with us again, in all the vivacious joy she created around her. In these words, and in her many novels, short stories, plays and films, Maeve lives on – and always will.

Gordon Snell, June 2013

School Outing

29 October 1964

O

ddly enough, the horror of a school outing is not the responsibility of looking after other people’s children in alien surroundings, nor is it the noise and possibility of them getting out of hand. The real problem is wondering whether they are going to be bored. The outing is so eagerly anticipated, and so much discussed, that it has to be an anti-climax – unless there are a few unexpected delights, like a teacher getting stuck in a hedge, or half of the sixth years being left behind in a chip shop, or someone getting involved with a man.

Of course, the real disaster is collecting the money. How often have I collected 38 times 18s. and spent it three times over before the day came when the man in CIÉ had to be paid?

Then there is the likelihood of someone getting sick; far from being able to minister to such unfortunates, I start to get sick myself, which undoubtedly heightens the awfulness for everyone involved. In all the years of hot bus journeys and twisty bends on the roads, and 12-year-olds eating four pounds of sweets in between bags of chips and bottles of Coca-Cola, no one has ever gotten sick, but I can never believe my luck will hold.

We went to Wales recently and to date this was by far the best outing. From the children’s point of view it was going to a foreign country – there would be Customs and foot-and-mouth spray on the way home. There would be new, strange Woolworths to investigate, there was a chance to see both the mail boat and the ferry, since we went out by the former and came home by the latter. They could even send postcards to people saying ‘spending a little while in Wales’ without elaborating that the little while was five hours. There was also Caernarfon Castle, the

raison d’être

of the whole visit, but no one gave that much thought.

From a teacher’s point of view, it also had everything to recommend it. It didn’t leave at a ridiculous hour in the morning; in fact we only left Dún Laoghaire at eleven-thirty a.m. Once you got them on the boat there was really nothing that could happen to them except the obvious and if that did happen someone would be bound to notice and stop the ship. Exploring the boat took most of the first hour, settling on a place for the mammoth eating of sandwiches brought us up to about two o’clock. Then there was an hour of everyone rubbing themselves with Nivea cream. After this the Welsh coast was sighted and approved of, and we got on to land and into a bus in a matter of minutes.