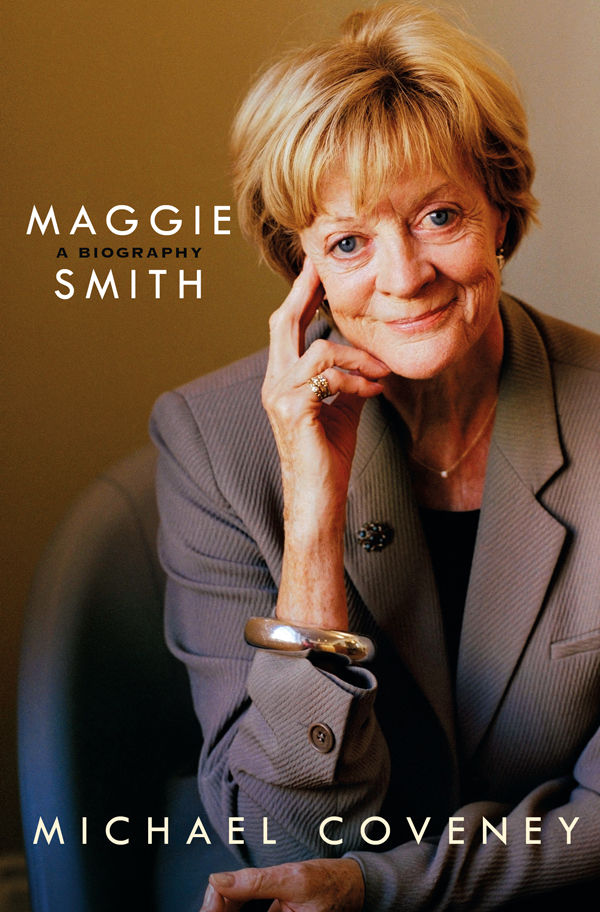

Maggie Smith: A Biography

Read Maggie Smith: A Biography Online

Authors: Michael Coveney

ICHAEL

C

OVENEY

M

AGGIE

S

MITH

A Biography

St. Martin’s Press  New York

New York

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click

here

.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

‘Of those whose business it is to imitate humanity in general and who do it sometimes admirably, sometimes abominably, some record is due to the world; but the player’s art is one that perishes with him, and leaves no traces of itself but in the faint descriptions of the pen.’

William Hazlitt

‘You have to have been desperately unhappy before you can play comedy, so that nothing can frighten you any more. And you can’t do tragedy before you know absolute happiness, because having known that you are safe.’

Edith Evans

In the Company of a Secret Star

‘I saw that Mary Smith in

Maggie, Maggie

…’ The play was really called

Mary, Mary

, and Maggie Smith liked the chance, overheard remark because it jumbled up her identity with that of a character who never existed. Actors use and subsume their personalities in the identities of figments. They want both to hide behind someone else and to show off. By moulding imaginary characters to their own physical reality, they unwittingly reveal themselves, or a small part of themselves. And yet, with Maggie Smith, the mystery remains. She is, for starters, very funny. But, like the greatest of vaudevillians, she believes that she only properly exists in the spotlight. What she thinks of the world – ghastly and depressing, on the whole – she believes is of no interest to anyone else. She is brilliant, and she can be demanding. But she is not grand, and she is not boring. At work, she is obsessive. She looks at all people, all vanities and all enterprises, with a mocking sense of disquiet and disbelief. Her fear and astonishment at the world, allied to her instinctive technical talent, and her innate intelligence, have made her a great stage actress in both comedy and tragedy, and an international film star.

She has gone from revue to West End stardom, from the Old Vic before the advent of the National Theatre, to distinction as a founder member of Sir Laurence Olivier’s first National Theatre company. She has won two Academy Awards, five

Evening Standard

best actress awards and, in recent years, achieved phenomenal worldwide success in the Harry Potter films and

Downton Abbey

. She was married for eight years to the vagabond actor Robert Stephens and had two sons with him. She disappeared from Britain for five years to lead the classical company at Stratford, Ontario, and to make films in Los Angeles. Her background is ordinary, her talent exceptional. Maggie Smith, even to those who know her best, is not only a mystery, but also an enigma.

‘A star is someone with that little bit extra,’ said Noël Coward, but the definition crumbles when you try to define ‘bit extra’. An audience knows a star when it sees one. On screen, the cliché is that the camera loves a star. In the theatre, certain basic qualities of stardom are quantifiable: total audibility, eye contact throughout the house, animal magnetism, the precise ability to convey the process of thought, and physical allure, even with the back turned on the audience. In Maggie’s case, the very pronunciation of her name stirs expectation and raises the spirits. As the journalist Bernard Levin once said, ‘There’s a glow around her, on stage and off, and everybody knows about that glow. It’s real.’ And yet, of all palpable stars, she is the last to place a boorish insistence on her status. Some big stars, such as Vanessa Redgrave and Helen Mirren, are perfectly charming and approachable people, but even in those two cases, the portcullis will descend at moments of crisis: they become elevated and remote. Maggie is unusual in that she behaves at all times as if she has no power or status whatsoever. On the night of her second son Toby’s professional stage début in

Tartuffe

in 1991 at the Playhouse in Charing Cross, she stood unostentatiously in the foyer sipping a glass of champagne with screenwriter Beverley Cross, her second husband, impervious to the first-night throng and totally unrecognised. At the same time, Maggie-watchers knew that the ‘Do Not Disturb’ signs were up.

Paradoxically for a show-off, Maggie Smith chisels away at her work with the monastic dedication of the instinctive recluse. In a golden age of British acting, she is distinctly quiet and ‘invisible’, even compared to such leading peers as Vanessa Redgrave, who is three years younger, and Judi Dench, who is just three weeks (nineteen days) older. She rarely appears on television as ‘herself’, gives very infrequent, guarded interviews to the press, lends her name to no causes (well, very few: the Oxford Playhouse, her ‘alma mater’ is one), her signature to no petitions, her prestige to no boards of directors. Life is difficult enough without the hassle of good works and deeds. And the pettiness of the theatre, the rapacity of the film companies and the vanity of acting, you feel, are phenomena Maggie just lives with as the price she pays for the demon within.

The stage director Peter Wood, who has known her all her working life, says that ‘psychological shingles is what she’s got, an inflammation of the personality ends’. The Oscar-winning costume designer Anthony Powell is reminded of ‘flayed anatomy, with those missing layers of skin, stripped away to show the formature of muscles and bones. She is more scared of being touched and hurt than anyone I know.’ The stage offers security in spite of all its dangers. In the theatre, Maggie forfeits her individuality in a curious distillation of her personality, and at last knows who she is, what she should wear and to whom she must speak. Off stage, she is beset with confusion and indifference on all these points.

Or at least, that is the appearance. ‘Dealing with her gift’ is the spine of her life, according to the actor Brian Bedford, one of her favourite leading men, and nothing much else interferes with that task. She worries endlessly at a text, like a dog at a bone, not to find a new laugh, nor to perfect a new trick, but to make a line, a passage and then the whole play, come alive again. She is renowned for never ceasing to dig and delve in her texts. In rehearsals, she will habitually withdraw from the company coffee break and be found poring over the script at the back of the room. Even on the last night of a run she will sit in her dressing room transfixed over her script, puzzling out what else it might contain. The director William Gaskill, who worked with her in the early days at the National, and is one of her most trusted colleagues, says that Laurence Olivier would arrive at rehearsal with his performance intact, deliver it like a gift and adjust it thereafter if necessary. ‘Maggie never has anything finished before she starts,’ he says, ‘which is why rehearsing with her is so exciting.’ And unlike many actors half her age, she still practises her scales and arpeggios. ‘Red lorry, yellow lorry’ is a drama student’s articulation exercise (repeated, fast, ad infinitum) she has never stopped using, like a trusty old toothbrush. She is fanatical about not putting on weight. She trains like a dancer.

Any attempt to ‘place’ Maggie in the annals of British acting is bound to consider her alongside Judi Dench and Vanessa Redgrave. These two were left to contest the crown of Peggy Ashcroft when Glenda Jackson departed the scene to pursue a life in politics as a Labour MP. Dench and Redgrave are, in a way, the Gladys Cooper and Sybil Thorndike of our day, while Maggie is certainly the Edith Evans. She has had notable success in many of Edith Evans’s roles – Millamant, Mrs Sullen, Rosalind, Cleopatra, Judith Bliss – and is the nearest we come to the idea of the chastely intelligent Anne Bracegirdle, for whom Congreve wrote his most famous female roles. Dame Edith’s background, like Maggie’s, had not a whiff of theatrical tradition; she was the only child of a minor civil servant in the Post Office and her mother, in Bryan Forbes’s phrase, ‘set great store by the proprieties’, as did Maggie’s. Her talent was instinctive, imaginative and untrained, and she had a way of finding words such as ‘basin’ inherently funny. Like Maggie, she never had to brazen it out in the provinces: ‘God was very good to me,’ she once said. ‘He never let me go on tour.’

Evans knew Bernard Shaw – she was his Lady Utterword in

Heartbreak House

, his Serpent in

Back to Methuselah

, his Orinthia in

The Apple Cart

and, after a protracted scuffle, his Epifania Fitzfassenden in

The Millionairess

, a role Maggie played so deliciously on television – but was not all that devoted: ‘He kissed me once. But I derived no benefit from it.’ Nothing was allowed to interfere with her theatre work, which amounted to sixty glorious, uninterrupted years after she had been discovered as Cressida in Streatham Town Hall by William Poel. She had no children and was loyally supported by a self-sacrificing husband whom she knew from her teens, and whom she married in 1925 and hardly ever saw, as he worked abroad for British Controlled Oilfields. Like Maggie, Edith Evans was intensely private off stage. She had no real interest in the material world and no ambition in conventional show business terms. And she first went to the Old Vic as a West End star. Unlike Maggie, she wasn’t innately funny or clownish, she did hardly any revue, made few films until much later in life (‘I don’t think I have a film face; it moves about too much,’ she once told reporters) and wrote quite a lot of letters.

Maggie could wrest Millamant and Mrs Sullen from Edith Evans because the performances were a fading memory among critics and audiences. But Evans’s Lady Bracknell in

The Importance of Being Earnest

, with its almost self-parodying haughtiness and deadly swoop on ‘a hand-bag’, bedevils any actress, thanks to its notoriety from the 1952 Anthony Asquith movie. Maggie herself used to do impressions of these intonations in her revue days. When Judi Dench played Lady Bracknell at the National Theatre in 1982, she brilliantly side-stepped all comparisons by portraying the tension and melancholy of a much younger dowager, non-stentorian and with the bloom still on, whose husband, dining alone with his meals on trays, was a considerable brake on her social and indeed sexual potential. Her success in the role did not obliterate Edith Evans; nor, to be fair, did Maggie herself when she finally delivered her surprisingly girlish and touchingly vulnerable Lady Bracknell in Nicholas Hytner’s revival of the play at the Aldwych in 1993, the start of their significant collaboration together.

But both performances were pretty good swipes at reclaiming the role from old-fashioned, gorgonesque eccentricity. And Dench has also had her mould-breaking Royal Shakespeare Company triumphs as Hermione/Perdita in

The Winter’s Tale

, and as Viola, Portia, the Duchess of Malfi, Beatrice, Lady Macbeth and Imogen in

Cymbeline

. She followed her Lady Bracknell at the NT with an equally unexpected, and equally memorable, Cleopatra. Any competition Maggie mustered at that time was confined to Canada, so that the impression, in Britain at least, was that Judi Dench had become our leading tragedienne. The release of feeling, a sort of glorious shiver with an instantly recognisable crack in her voice, characterises all these Dench performances. The renewed monstrosity of Bracknell she left to Maggie to accomplish when she got round to her second Aunt Augusta in

Travels with My Aunt

(Lady Bracknell’s Christian name was adopted by Graham Greene for his nomadic gorgon); you could say that she ducked the challenge. Dench generously concedes, though, that it is Maggie’s extraordinary way of looking at the world that marks her out, her delightful sense of the absurd: ‘She does things in such a daring way that she leaves me standing. She also leaves me laughing.’

Everyone loves Judi Dench, just as everyone loved Ellen Terry. But her drive is of a different calibre to Maggie’s, less gnawing, less obsessive. John Moffatt, who was in that first Old Vic company with both ‘Jude and Mags’ said that Maggie, like Paul Scofield, is possessed by a demanding and driving genius, but that she also skirmishes in the realms of camp by inhabiting a world that is peculiarly her own, rather as the revue star Beatrice Lillie did. Maggie loves a line of Bea Lillie’s, said of a hopeless case leaving the stage: ‘She’ll never find the kitchen, she’s that moody.’ And, as Maggie’s performances are often a series of elaborately contrived masks that proceed to disintegrate, she further arouses interest in what she might really be like under the skin. As the director Peter Hall says, ‘When the public sees Maggie Smith in a play, the public becomes voraciously interested in what kind of person Maggie Smith is.’ There are various points of similarity between Maggie and Judi Dench, but that is not one of them. Judi Dench is known to be a cosy, comfy creature with good manners, good breeding and a pronounced liability to burst into giggles and gales of laughter. Everything is more dangerous, acidulous and beadily observed with Maggie.

This is not a value judgement on their respective talents. But Maggie, especially in comedy, presents the role, while Dench puts herself in its centre and works outwards, negotiating the limits of her own characterisation at the same time as she meets the rest of the actors and the surrounding production. This method leads, not all that surprisingly, to the occasional aberration in the costume and wig departments, where Dench is often reprehensibly careless. Maggie never makes such mistakes. With Vanessa Redgrave, the contrast is even greater, and has been well made by Simon Callow. ‘To work with Maggie and then with Vanessa,’ says Callow, speaking from experience, ‘is to go from alpha to omega. They are the Gielgud and the Olivier in the sense that they represent absolute opposites. Vanessa inhabits poetic states and becomes infused with them; but what they are, and where they come from, is entirely mysterious. Maggie, on the other hand, is interested in a particular truth at every moment, and she goes at it like a forensic scientist. She never stops. Vanessa is so much more intuitive, and random; she throws a casual light over something, and because nobody’s ever had such a strong beam before, you see all kinds of things reflected.’

Callow believes that Maggie, like Olivier, finds a kind of sanity only in technical craft: ‘They are both tremendously needful personalities who don’t go into “acting” at all, and must externalise what they do. But if it were only that, you wouldn’t be interested in them. Maggie plucks at the script and says, “What am I supposed to do – I mean – I mean, you say – I mean, it’s supposed to be funny.” Then you say, “It’s supposed to be funny,” and she will press a button and go into comic mode, and what you have written or translated becomes like Congreve. For Vanessa, you have to create a whole imaginative framework, which takes about five hours to get across. You can’t just say, “This woman hates men.” Once Vanessa finally takes such an idea into her imaginative world, she takes it on completely. But one idea, put simply to Maggie, can instantly go through her whole performance. She is ecstatic at such moments and becomes the most beautiful, physical and most alive woman you have ever seen in your life.’