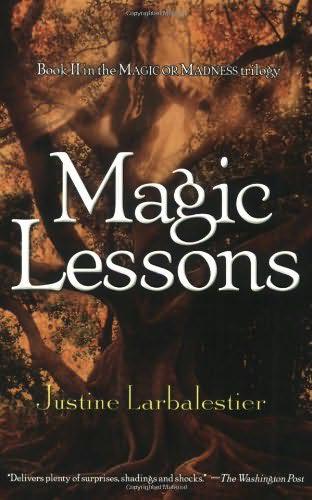

Magic Lessons

Authors: Justine Larbalestier

by Justine Larbalestier

Magic Lessons

Also by Justine Larbalestier

Magic or Madness

Magic Lessons

by Justine Larbalestier

Magic Lessons

RAZORBILL

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Young Readers Group

345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Copyright 2006 © Justine Larbalestier All rights reserved

Interior design by Christopher Grassi

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Larbalestier, Justine.

Magic lessons / by Justine Larbalestier.

p. cm.

Summary: When fifteen-year-old Reason is pulled through the magical door connecting New York City with the Sydney, Australia, home of her grandmother, she encounters an impossibly ancient man who seems to have some purpose in mind for her.

ISBN: 1-4295-9066-1

[1. Magic—Fiction. 2. Space and time—Fiction. 3. New York (N.Y.)—Fiction.

4. Sydney (N.S.W.)—Fiction. 5. Australia—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.L32073Mafu 2005

[Fic]—dc22

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For Niki Bern, best sister in the multiverse

Note to Readers

Like the first book in this trilogy,

Magic Lessons

contains both Australian

and

American spelling, vocabulary, and grammar. Chapters from the viewpoint of the Australians, Reason and Tom, are written in Australian English, and those from Jay-Tee’s point of view are written American style. You will find

synaesthesia

in the Australian chapters, but

synesthesia

in the American. If any of the words are new to you, turn to the glossary, where you will learn that being

jack of

something means you’re

over it

, and that a

dog’s breakfast

is a

mess

.

Reason Cansino

Once, when I was really little, we passed a road sign pep

pered with bullet holes. It was pretty much the same as any of the other road signs we passed out bush, but this one I read aloud in my squeaky toddler voice: “Darwin, 350. Two times 175. Five times seventy. Seven times fifty. Ten times thirtyfive.”

My mother, Sarafina, clapped. “Unbelievable!”

“How old is the kid?” asked the truck driver who was giving us a lift to the Jilkminggan road. He glanced down at me suspiciously.

“Almost three.” Sarafina was seventeen.

“Not really?”

“Really.”

When we arrived, three of the old women—Lily, Mavis, and Daisy—sat down with us on the dirt floor of the meeting place. They gave us tucker—yams, wild plums, and chocolate bickies to eat, and black-brewed, sticky-sweet tea to drink. A posse of kids hung around, darting in and out for plums and bickies, but mostly stood just out of reach, watching and giggling.

A few gum trees dotted the settlement, their leaves a dull green, standing out amongst the dirt, dry scrub, and ant hills taller than a man. Healthier, greener trees, bushes, and vines grew farther away, on the other side of the buildings, where the ground sloped into the banks of the Roper River. The buildings were low, made of untreated wood and rusting corrugated iron. The only one with four walls, a proper door, and windows was the silver demountable where school was held— the hottest, most uncomfortable building in the settlement.

“You’re that travelling woman, eh?” Daisy asked. “With all them different names?”

Sarafina nodded.

“What you want to be called now?”

“Sally. And my daughter’s Rain,” Sarafina said, even though my name is Reason.

“We hear about you,” Daisy said. “You been all over, eh? All the way down south, too?”

“Yes,” Sarafina said. “We’ve been all over Australia.”

“Seen lots of white man places, too?”

“Some.” Sarafina always stayed away from cities so that her mother wouldn’t find us. “I like Aboriginal places better.”

The three women grunted as if this were to be expected.

“That little one, that Rain,” Daisy said, looking at me. “She’s countryman, eh?”

Sarafina nodded.

“Her father countryman, innit?”

“Yes.”

“Where him from?” Mavis asked. She was the oldest of the three women. Her hair was all white and her skin was so black it shone. She took a piece of chewing tobacco from behind her ear and put it in her mouth.

“I don’t know.”

The three women murmured at this. “Don’t know?”

Sarafina shook her head.

“Who his people?”

“Don’t know.”

“Them from desert country? Arnhem country?”

Sarafina shrugged. “He didn’t tell me.”

Daisy nudged Lily. “That little one, Rain? Him amari? Him munanga, I reckon.”

“True,” Lily said, “but him daddy still got country.” She turned back to Sarafina. “Where you meet him?”

“Out west.” Sarafina gestured past the water tank resting on a huge mound of dirt, to the horizon where the sun would set.

“How long you him together?”

“One night.”

They nodded at this. “Drunken fella?”

Sarafina laughed. “No.”

“Him from bush or white man place?”

“Bush.”

“Ah,” Lily said, pleased to be given something solid. “Stockman?”

“I don’t know.”

“Him barefoot or got boots?”

“Boots.”

They nodded again. “Stockman.”

Sarafina made flashcards. She cut up an old cardboard box that had once held cartons of Winnies, and she wrote on them with a fat black Texta she’d bought in Mataranka.

She wrote the names of nine recent places we’d either stayed or seen road signs for: Darwin, Jilkminggan, Katherine, Mataranka, Ngukurr, Numbulwar, Borroloola, Limmen Bight, and Umbakumba; the names of all the planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto (though she said the last one wasn’t

really

a planet); and the branches of mathematics: foundations, algebra, analysis, geometry, and applied.

We sat on the dirt floor under a roof of paperbark. Occasionally strands of it would drift down and land on us. The three women sat cross-legged, gutting a kangaroo and waving the flies away.

Rain?”

“Teaching her how to read.”

They all nodded and agreed reading was important, though

Sarafina held up the cards with one hand, waving flies away, and patting one of the dogs with the other. The sky was the intense blue that only happens when the earth is the red-brown of iron. Not one cloud. Dry season. There would be no rain for months.

Sarafina held up the next card. “Nnn . . .” I said, trailing off, staring at the card with its

n

and

g

and

k

and

r

’s and

u

’s. I wasn’t sure if I’d seen it before. I didn’t understand how those letters went together to make sounds.

“Ngukurr,” said Lily, sliding past the

g

that had confused me. Her people were from there. She knew how to read that one.

Sarafina put the cards down, realising she should, perhaps, have started with the alphabet. For the next two hours we sang, “A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H-I-J-K-L-M-N-O-P-Q-R-S-T-U-V-W-X-Y-Z.” The old women laughed and lots of the kids joined us, some of them sneaking out of school in the demountable, with the drunken white teacher. I informed Sarafina that

f

,

j

,

q

, and

z

were my favourites.

Annie, Valerie, Peter, little Rabbit, and Dave said they liked

s

best, so Sarafina invented an

s

dance for them. This involved standing up, putting your hands above your head, pushing your hips to one side and your shoulders to the other, and shimmering like a snake.

We all

s

-danced, falling down and snake-bellying away across the ground, coating ourselves with red dirt. Everyone was good at it except me. I was too little and unco. Sarafina was the best, even though she was the only whitefella, faster and more shimmery than anyone else. We all laughed.

The dogs barked and jumped up, running in circles, trying to join in, but they weren’t good at moving on their bellies and kept rolling over, trying to get us to rub them instead. They didn’t look like snakes at all.

When we were all danced out and tired and the women had the kangaroo roasting amongst the coals, Mavis told us the story of the mermaid ancestor and how she’d made the land. She had many names, but Mavis said munga-munga was best.

I dreamed about her that night and many nights, but in my dreams when she made her giant path across the country, sparkling numbers and letters spilled out from her tail, littering the red earth, turning into valleys and rivers and hills and ocean, drifting up into the sky and becoming the planets and the stars.

8

Once, when I was ten years old and Sarafina twenty-five, I lost my temper. Sarafina had always told me never to lose my temper, but she never told me why.

I’d only been at the school for a week. It was my first and last time in a real school, one where you had to wear shoes and be quiet when the teacher spoke and not leave the classroom unless the teacher said you could, but also one where there were lots of kids and games and books about things I’d never heard of. I was really hoping I’d be able to stay.

I was being called Katerina Thomas and my hair was cut short and dyed light brown, almost blonde. I still looked like me, though.

Josh Davidson was the class creep. He’d go around snapping girls’ bra straps (those that had them), calling them bitches, and, when he could, cornering them and trying to touch their breasts (even if they didn’t have any yet). He was taller than the other girls and boys, stronger, too.

He was a lot taller than me. He’d already tried to snap my non-existent bra, and I had a bruise on my arm from where he’d grabbed me when I was coming out of the bathroom. A teacher had turned the corner and told him to let me go before he could do anything else.

The next day in class, Josh sat next to me. He pushed his chair as close as he could. I felt fear and anger inside me like an intense heat. He didn’t try to touch my breasts; instead, he put his hand on my thigh. I held my knees tight together. Put my hand in my pocket to hold my ammonite.

I felt my anger getting bigger, uncoiling inside me. There was a scream, but I didn’t open my mouth. The stone in my pocket grew warm and sweaty as I clutched it tightly. The rage was like a wave, starting small, then spiralling out of me. Growing bigger and bigger, as fast and beautiful as Fibonacci numbers: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597 . . . My eyes exploded in blinding red light.

Someone yelled out, something about a doctor.

Then, for a moment, I could see. The intense light in front of me faded away. Josh was on the floor. He wasn’t moving. I felt glorious, better than I had ever felt in my entire life. Then I fainted.

It was hours before I discovered that Josh Davidson was dead. An aneurism, they thought. The blood in his head had lumped together, had stopped the oxygen getting to his brain.

Had I made his blood do that?

I didn’t ask Sarafina, but that night we left. Not just the town but the state—we went all the way across the country, as far as we could get. No more school for me.

We never talked about it, but after that, Sarafina’s warnings about not losing my temper came even more often. Without explanation.

I know now. I stopped that boy’s blood. I killed him.

I’m magic, like my mother, but she never told me. She didn’t tell me that if I lose my temper, people might die. She never told me that if I don’t use my magic, I’ll go mad, like her. Or that if I do use it, I’ll most likely die before I turn twenty. She never told me to choose between magic or madness.

Sarafina didn’t tell me anything.

Back to the Asylum