Magnus Merriman (36 page)

Authors: Eric Linklater

Johnny Peace, the village shoemaker, was a witty fellow who could make rhymes and who knew all the gossip of the country. He was a young man and lived alone. His shop was a favourite gathering-place, and rarely an evening passed there without debate of some kind. He was, however, alone when Magnus went in, and readily agreed to have a drink. Johnny Peace already knew everything that had happened during the storm for several miles around, and he himself had had an adventure, for on his way to one of the village shops he had encountered the schoolmistress coming down-wind like

a full-rigged ship. âIf she'd had a bone in her mouth the picture would have been complete,' he said. âBut God! she ran aground. She came full-speed against me and flung her arms round my neck. “It's the wind,” she said, “I can't help it, Mr Peace, I give you my word I can't help it!” But from the way she hung thereâand she's no lightly madeâI doubt she was just waiting for the opportunity, and the next time there's a hurricane I'm staying safe at home till she's safe in the school.'

Jock of the Brecks arrived while they were talking, and after having some of Magnus's whisky he related his own experiences in the storm, and took another drink. The topic was hardly exhausted when it was found that the bottle was empty, so Johnny Peace shut his shop and they went to the village inn, where they drank beer till closing-time. It was Saturday night and the shops were still busy. Under the gable-end of one of them a little group of men and boys stood sheltering from the snow that now was falling. Before the lighted windows the flakes descended in a thick but gentle flurry. After the inn had closed its doors Magnus and his friends talked awhile with the casual bystanders, and then Johnny Peace proposed they should return to his shop. They added the blacksmith to their number, and Johnny produced another bottle of whisky.

After an hour or so the blacksmith went home. Half an hour later Jock of the Brecks went home. But Magnus stayed where he was, for Johnny Peace was a fine congenial soul, and by now Magnus had reached that state of mind in which talk seems infinite and infinitely desirable. He wanted to tell Johnny about the War and about India and about America; about the books he had written and the book he was going to write; about love and death; about women he had known and about his plans and hopes for Peter and Peerie Mansie. And Johnny, though a gifted talker himself, was sympathetic and a patient listener. Long after the bottle was empty Magnus talked on, and Johnny agreed when agreement was required, and deprecated that which it was politic to deprecate. At last he fell asleep, and Magnus bore him no ill-will, for the load of speech was almost off his mind and he felt free of a great burden.

He went out, and saw that the world had turned white. A virgin landscape lay before him, starlit and placid. The air was clear and the fallen snow was faintly luminous. It had raised the dykes to a new level and smoothed the rough ground with gentle undulations. Magnus beheld that blanched serenity with drunken ecstasy.

The cobbler's shop was a little distance from the road and a little higher than the road. Sheltered by a wall the down-hill path from its door Was but thinly covered with snow, and Magnus mounted his bicycle. At the corner he ran into a drift and fell heavily, striking his chest on the upturned grip of the handle-bar. When he got up he felt sick and there was a dull pain under his heart. He stood for a moment or two, swaying slightly, and the odd determination of drunkenness took him: he had started to go home and he would continue to go home. But the snow lay deep on the road, it was nearly a foot deep, so he left his bicycle where it had fallen and began to walk. He moved slowly, for his feet sank at every step and the pain in his side made it difficult for him to breathe. He walked on, head down and half-dazed. Presently, despite the pain, he felt curiously happy. His heavy plodding walk became a slow rhythm and he took a childish joy in crunching through the snow. A part of his brain was sleepy and inactive, but another part was intensely alive to a multitude of small impressions. He perceived the shape of the snow-filled ditches with singular delight, and the lurching rhythm of his own walk seemed enchanting. He looked at his feet, rising and falling, sinking and reappearing, with great amusement, and the dark gable of a cottage, neatly roofed in white, held him for a minute of exquisite pleasure. The countryside appeared to fall away from the road in endless folds, and the suave and simple lines were delicious to see.

In timeâhe did not know how longâhe came to the farm-road to Mossetter, and slowly climbed uphill. He stopped to rest awhile, and turned and saw beneath him a starlit maiden land, stained with the star-twinkling darkness of the great loch, spreading in dusky whiteness to the white round breasts of Hoy. Twin hills they stood, snow-clad, round as the buxom breasts of a girl, and flatly before them lay the

white map of Orkney. And now a new drunkenness came to Magnus, but whether of his belly or his soul he did not know. Tears sprang to his eyes to see such loveliness, and perception like a bird in his breast sang that this land was his and he was one with it. As though his tears had flooded it his mind was filled with knowledge and he knew that his life was kin to all the life around him, even to the beasts that grazed in the fields, and to the very fields themselves. Live was the flowering of a single land, and love of country was no virtue but stark necessity. Patriotism and the waving of flags was an empty pride, but love of one's own country, of the little acres of one's birth, was the navel-string to life. His life, as the life about him, was the vigour of his blood, and life could not be whole save in its own place. Now he knew why, in far parts of the world, he had often felt the unreality of all he saw and descried a foolish artifice in his own business there. The far parts of the world were fine roving for pirates who had a secret island whither they might bring back their booty, but to roam the world without a haven or a home was to be lost as a star that fell to nothingness through the ordered ranks of heaven. Now he knew why, in late months, time had passed so simply and untroubled. This soil was his own flesh and time passed over him and it like a stream that ran in one bed. Here indeed he was immortal, for death would but take him back to his other self, and this other self was so lovely a thing, in its cloak of snow, in the bright hues of spring, in the dyes of the westering sun, that to lie in it was surely beatitude.

His thoughts grew feebler and more diffuse. He shivered, and felt the cold. The pain in his side was a dull aching. He turned homewards and wearily climbed the hill.

Rose was waiting for him. She had sat by a dying fire, anxious and angry. She came to the door, and her voice was hard enough to shatter any dream less firmly set and safely guarded than Magnus's. But Magnus's dream of knowledge was now like a bubble of pearl in the depths of his mind, and girded round with sleep.

âDo you know what time it is?' she demanded. âWhat have you been doing till now?'

âTalking,' said Magnus. âTalking and seeing the world.'

Rose came nearer him and sniffed. âYou're drunk!' she said.

âNot drunk, but sleeping,' said Magnus, and stumbled indoors.

Like the storm of the preceding night Rose's temper gathered strength in the darkness and as soon as daylight came Magnus was wakened by her angry voice. Had he been guilty of treason, regicide, and all infamy she could not have assailed him more bitterly. Drunkenness was to her the blackest of sins, and her tongue lashed him like scorpions. Hearing her so loud the children began to cry, and the house was filled with the noise of wrath and weeping. But Magnus lay and said nothing till the worst seemed over.

âWell, are you going to get up or do you mean to lie in bed all day?' asked Rose, a little breathlessly.

âI think I'll stay in bed,' said Magnus.

âYou'll do no such thing!' said Rose.

âAll right then. I'll get up. I fell and hurt myself last night and I'm pretty sure I ought to stay in bed; but if you don't want me to, I shan't.'

Magnus sat up and threw back the clothes. Then he began coughing, and coughed up a little blood.

âThere!' he said. âI told you I had hurt myself. I've broken a rib, I think.'

âStoop!' [The rude imprecative.] said Rose. âYou've spoilt your stomach with whisky, that's all.'

Magnus lay down again. âI think I'll stay in bed however,' he said.

âAll right,' said Rose, âthen you can mind the bairn till I'm ready for him.' And she planted the still wailing child in Magnus's arms and left them to go about her work.

Although it was Sunday she worked with great vigour all day and made as much noise as possible. Nor did she cook any dinner, but some time in the afternoon brought Magnus a cup of tea and a slice of thick bread and butter, saying, âThere's no use cooking anything, for

you couldn't eat it anyhow, after drinking like that all night.'

âAs it happens I'm feeling very hungry indeed,' said Magnus.

âYou don't need food when you lie in bed all day,' said Rose, and went away to make a great clattering noise by rearranging all her pots and pans in the kitchen.

And Magnus lay and remembered his beatific vision of the world washed white and unified by snow, and the bubble of pearl in his mind was unbroken by the clatter of pots and his wife's anger. Peerie Mansie slept in his arms and Peter played on the floor at the bedside.

On the following morning the pain in his side was worse, and Rose consented to send Johnny for the doctor. The snow had frozen hard and the roads were passable now. But scarcely had Johnny gone than Peggy of the Bu came to tell of a great and splendid scandal in the country, and this news put Rose in a worse temper than ever.

The snow on Saturday night had played falsely with a hundred lovers. In Orkney it is the habit to go a-wooing on Saturday night, and to court your girl not in cold corners but warmly, yet with circumspection and restraint, in her bed. But though everyone knows of this practice, and, if they are young enough, looks forward eagerly to the week-end's darkness, there is a certain decorum used and the custom is not openly talked about. And now the heavy snow had betrayed what convention would fain conceal. For the Saturday lovers, arriving when the sky was clear or merely a flurry of snow was falling, had stayed longer than Magnus had stayed with Johnny Peace, and risen to find the snow deeper then he had found it.

Many had come long distances, and now their bicycles and motor bicycles were useless to take them home again. Sometimes indeed they were hard to find, for if they had been left at the weather-side of a wall the banking snow had covered them. So the lovers had to walk home, and the motor bicycles, too heavy to push through the snow, had to be left behind as evidence against their owners.

Sunday morning was bright and sunny, the snow had

stopped falling, and over its smooth fields the deep telltale footprints led from every house where lived a comely or a kindly girl. Far across country they stretched, and everyone could tell at a glance that Jessie and Jean and Molly and Minnie had slept with their boys beside them. And it was worse still for the boys, for some of them had so far to go that when respectable folk set out for church they met them still slowly trudging homewards, some with their bicycles on their shoulders and others with embarrassing memories of where their bicycles had been left.

This was the story that Peggy of the Bu, laughing and delighted, told to Rose, and Rose's anger mounted with every sentence. For her man had also been out on Saturday night, and left his bicycle in the snow, and it would be said that he, a married man, had been running after the lasses, and so her pride would be shent and her name sullied beyond redemption.

When Peggy had goneâshe had not been allowed to see MagnusâRose came ben and fiercely told him all this. It was in vain that Magnus declared his bicycle had been left outside the shoemaker's shop and that no one was likely to think he had been sleeping with Johnny Peace. She would not be comforted. She was sure that scandalous tales would be told, and how could she deny them when it was clear that Magnus had been out so late? Her distress was genuine and she vented it in anger.

Nor was her wrath diminished when the doctor came and said that Magnus had indeed broken a rib and must stay in bed for several days. She contained herself while the doctor was present and listened to his instructions with grim politeness, but when he had gone she told Magnus that it served him right and he need expect little care and less sympathy while he lay abed.

âI've got my work to do,' she said, âand you could be doing yours if you'd had the sense to behave yourself and keep away from the drink. And keep away from Johnny Peace too, after this! Johnny Peace, indeed! It's all right for him if he likes to spend all his money on whisky, for he's a single man and has only himself to spoil. And

a fine name he has through the country for his talking and drinking! But you're married and you've a family for bye, and the thought of you drink, drink, drinking with Johnny Peace fair makes me mad. And you haven't the stomach for it, I say! You fall off your bicycle and break your ribs and let everyone know you were out past midnight when a decent man should be at home in his bed, and God knows where they'll say you were, for there's lasses about that would let anyone in, married or no. But heaven help you if you get drunk again, for there's never any knowing what you'll do when there's a dram in you. You were drunk, I'll warrant, though you never admitted it, when you bought Jupiter, and what use was he to you? Nothing but the waste of a hundred poundsâbringing a bull like that into a peerie farm like this!âand that's more money than you'll ever make again, for you're getting lazier every year, and so long as you have a book to read there's little enough work to be got from you. Have you mended that harness yet? Not you, faith. But you'll read your books whatever happens, and never a thing they'll do for you in return, no, no more than Jupiter did.'

Magnus waited patiently till her tirade was done and she had gone. The harder she talked the harder she would work, he thought, and there was comfort in that. Then he reached under his pillow and brought out

Candide,

Pride and Prejudice

, and

Madame Bovary. Candide

he put aside: some disturbing association clung to it, though he could not think what it was nor discover whose memory it

nearly evoked

. And after turning a few pages he put away Madame Bovary, for the account of Hippolyte's operation had always made him unhappy, and, with his ribs newly strapped, he did not care to read about tenotomies and the like. But opening

Pride and Prejudice

he chanced to read Mrs Gardiner's query, âPray, how

violent

was Mr Bingley's love?' and Elizabeth's reply, âIs not incivility the very essence of love?' Rose, he concluded, must still be very deeply attached to him, for she had carried incivility to its extreme, and he rejoiced to find so applicable a sermon in the smooth tones that underlay the

running brook of Jane Austen's silver fluency. He read for an hour and thought how much pleasanter it was to read fine writing, to note the coolness of others' wit, than to write unhandily a book of your own and thrash your wits till they brought forth at last a mouse of wit that might be written down. And he thought with satisfaction that although his wealth was only a few hundred pounds he had more books than many a richer man. He had enough to last him. He would not need to buy any more.

On Tuesday Rose was in no better a mood and Magnus decided that her ill-humour would endure for the week at any rate. She contrived new ways to make him uncomfortable. She took away his cigarettes, and found the books under his pillow and took them away also.

âYou've wasted enough time reading,' she said sourly.

âWell, I can't do anything else at present,' said Magnus.

âYou can mind the bairn,' she said, for Peerie Mansie was crying loudly. She put the child in Magnus's arms. âIf you can manage to keep him quiet you'll be clever enough, and you'll have no time for books,' she said. âAnd keep an eye on Peter, he'll be getting into some mischief or other if you don't. I've my washing to do.'

While Rose scrubbed clothes in the back kitchen Magnus endeavoured to pacify his younger child. But Peerie Mansie had taken a dislike to the world about him and would not be quiet. So Magnus thought of the principle by which a great pain may drive out a less and a large noise subdue a small one, and began to sing. And the first song he remembered was the disreputable ballad of

Samuel Hall

. Peerie Mansie evidently enjoyed it, for he stopped his crying almost at once. Magnus came to the third or fourth verse, and, though it hurt his side somewhat, sang louder than ever:

Then the Parson he will come, he will come,

And the Parson he will come, he will co-ome!

The Parson he will come

And he'll look so bloody glum,

And he'll talk of Kingdom Come,

Damn his eyes, blast his soul!

The comminatory refrain he sang in fine full-throated fashion, and before the last note had died the door was thrown open and Rose stalked into the room.

âWhat's that you're singing to my bairn?' she cried. âThat's no a song for a bairn to hear, no, nor any decent body either!'

âWhy, have you been listening?' asked Magnus.

âYes, I've been listening, and I wonder you're not feared of a judgment, singing a song like that, and to a bairn.'

âMansie thoroughly enjoyed it. He stopped crying at once.'

âPoor wee bairn, my poor wee bairn,' said Rose, and rocked Peerie Mansie in her arms. The child immediately began to cry again.

âGive him to me,' said Magnus. âI can keep him quiet.'

âPoor wee bairn,' said Rose again, and still without effect.

She grew impatient. âHere, take him then,' she said, and gave him back to Magnus. âBut mind and not let me hear that song again, nor any other like it!'

When she had gone Magnus sang once more, but softly now, the ballad of

Samuel Hall

, and Peerie Mansie fell sound asleep.

Magnus called to his elder son: âCome here, Peter. I want you to do something for me. I want you to get me a book. A book, do you understand? Any book you like.'

Peter obediently went to the shelves in the ben-room and brought back a tattered red volume. It was

Greek

Rudiments

.

âWell,' said Magnus, âI had hoped for something of a more definitely literary interest than this: something more finished, more accomplished, and so more entertaining, if you take my meaning. But if you think I should continue to polish up my Greek I suppose there's little use in asking you to go back for a novel. No? One book's enough, is it?'

Peter tried to climb on to the bed and Magnus lifted him up and settled him against his knee.

âWould it amuse you to hear the Athenian tongue?' he asked.  Â

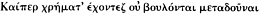

that means, “Though they have money they will not share it with the poor”; and that shows you the

that means, “Though they have money they will not share it with the poor”; and that shows you the

benefit of a classical education, for you discover by it that human nature doesn't change much. “Share my  with the poor?” said the Peloponnesian War profiteers. “Not bloody likely!” And so say all of us, Peter, yet not knowingâunless we have had a classical educationâthat that sentiment, like all notable or worthy sentiments, was already a commonplace on Athenian pavements some two thousand five hundred years ago.' And Magnus solemnly repeated the Greek sentence.

with the poor?” said the Peloponnesian War profiteers. “Not bloody likely!” And so say all of us, Peter, yet not knowingâunless we have had a classical educationâthat that sentiment, like all notable or worthy sentiments, was already a commonplace on Athenian pavements some two thousand five hundred years ago.' And Magnus solemnly repeated the Greek sentence.