Male Sex Work and Society (57 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

History of Male Homosexuality and Male Prostitution

It is generally believed that most ancient Asian countries had a longstanding tradition of same-sex desire and sex/gender ambivalence, which was ended by the rise of modernity and colonialism (Altman, 1995). China seems to fit this pattern, given its well-established literature dealing with a history of strong homo-social culture (Louie, 2002); a tolerance of men with same-sex desires (Hinsch, 1990; Ruan & Tsai, 1987; Samshasha, 1997; Van Gulik, 1961, pp. 62-63); and admiration for men who had feminine beauty (Song, 2004). The stories of

yutao

(peach remainder) and

duanxiu

(cut sleeves) were the origins for the two most famous and commonly used euphemisms for male homosexuality in Chinese literature. The first story tells of Duke Ling of Wei and his male

chong

(favorite), Mi Zixia, who lived in the Zhou Dynasty (1122-256 BCE). Mi Zixia tasted a piece of peach, found it sweet, and then gave the rest of the peach (the “remainder”) to the king, his action showing the passion between the two. The second story concerns Emperor Ai and his male chong Dong Xian in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 AD). The two were sleeping together on a couch when the emperor was suddenly called on to attend to state business. In order not to wake his lover, the emperor took his sword and severed his sleeves (thus “cut sleeves”) on which his lover was resting.

yutao

(peach remainder) and

duanxiu

(cut sleeves) were the origins for the two most famous and commonly used euphemisms for male homosexuality in Chinese literature. The first story tells of Duke Ling of Wei and his male

chong

(favorite), Mi Zixia, who lived in the Zhou Dynasty (1122-256 BCE). Mi Zixia tasted a piece of peach, found it sweet, and then gave the rest of the peach (the “remainder”) to the king, his action showing the passion between the two. The second story concerns Emperor Ai and his male chong Dong Xian in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 AD). The two were sleeping together on a couch when the emperor was suddenly called on to attend to state business. In order not to wake his lover, the emperor took his sword and severed his sleeves (thus “cut sleeves”) on which his lover was resting.

The reason for this tolerance of same-sex love may be that social conceptions of male sexuality at the time were primarily concerned with conformity to power hierarchies. Behavior that might be considered inappropriate by contemporary standards was permitted, as long as one maintained one’s social obligations to the family (i.e., getting married and bearing children) and avoided excessive sexuality, such as masturbation and prostitution (Louie, 2003). In other words, masculinity was understood not only in relation to sexual identity or orientation but also in relation to familial roles and social expectations, such as being a loyal son with the ability to control sexuality (Berry, 2001; Kong, 2011a, pp. 151-152).

This tradition of same-sex love allowed same-sex prostitution to develop, especially among the rich. Benevolent emperors or lords in royal courts would give their beloved an official title. Later, in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), this evolved into rising classes of merchants and officials having full-time favorites or hiring part-time prostitutes, which led to a highly developed public system of male prostitution (Van Gulik, 1961, p. 163). It is worth noting that records of this time show that almost all the male prostitutes were flamboyantly effeminate and young, and were assumed to take on the passive sexual role (Hinsch, 1990, pp. 89-97). In contrast to adult males, who were seen as powerful and impenetrable, male prostitutes represented the powerless and penetrable, thus assuming the same role as youth or women in an age of sexist hierarchical systems (Sommer, 1997).

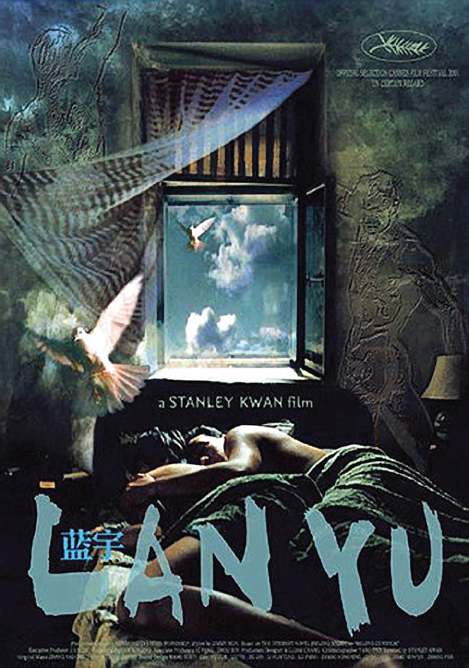

FIGURE 13.1

A clip from the film

Lanyu

. The movie revolves around a poor student who sold his virginity to his first client. (Director: Stanley Kwan, 2001)

Lanyu

. The movie revolves around a poor student who sold his virginity to his first client. (Director: Stanley Kwan, 2001)

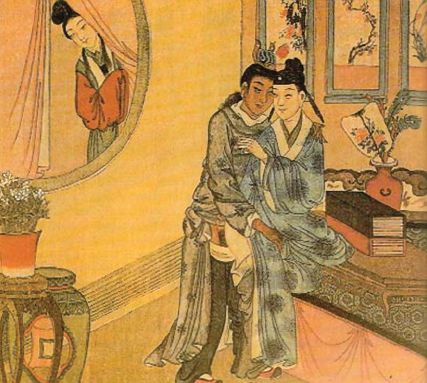

FIGURE 13.2

Chinese painting,

Woman Spying on Male Lovers

, depicting male homosexuality in ancient China.

Woman Spying on Male Lovers

, depicting male homosexuality in ancient China.

Homoerotic practices between men continued up to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), when—perhaps as a reaction to the permissiveness of the individualistic Ming period—homosexuality was subject to increased regulation in an attempt to strengthen the Confucian idea of the family (Hinsch, 1990, ch. 7; Ng, 1987, 1989). The end of the male same-sex love tradition seems to have occurred when Republican China underwent intense nationalism and state building in the course of Westernization and modernization. Proper control of sexual desire (e.g., the regulation of masturbation, prostitution, and homosexuality) was seen as being the key to the development of the modern nation-state (Dikötter, 1995, pp. 126-145). On top of this, a new Western medical discourse, which used Havelock Ellis’s medical theory of homosexuality to dichotomize sexual normalcy and deviation, began in the 1920s (Kang, 2009, pp. 52-59; Sang, 1999). In the Mao period (1949-1976) and the early reform era (1978-1990s), homosexuality not only was pathologized and silenced but was increasingly seen as deviant and criminal, with a homosexual being called a “hooligan” in Article 160 of criminal law in 1979 (Kong, 2011a, pp. 152-156).

In terms of prostitution, the focus has overwhelmingly been on women. This continued with the Republican ideal of eliminating female prostitution as a national shame, with the Chinese government in the Mao period claiming to have successfully eradicated female prostitution as a remnant of imperialism, a sin from the West, a brutal form of sexual exploitation, and an obstacle to socialist revolution. This continued until the reform era, when the government was forced to admit the resurgence of female prostitution (Hershatter, 1997). In contrast, male prostitution did not attract any serious government or media attention until the 1990s, a period marked by a rapid increase in visible gay venues, such as bars, clubs, massage parlors, saunas, and karaoke rooms, and the spread of HIV infection among men who have sex with other men (China Ministry of Health et al., 2006, p. 2; Kong, 2008; Wong et al., 2008; Zhang & Chu, 2005).

Social Contexts for the Emergence of the Male Sex Industry in Contemporary China

The emergence of contemporary male prostitution can be understood in the context of the reconfiguration of the “capitalist” market and the “socialist” party-state in reform China, which has generated new forms of possibility and control on both the societal and individual level (Rofel, 2007; Wang, 2003; Zhang & Ong, 2008). First, as I argue elsewhere (Kong, 2012), the state’s opening to the global economy has boosted the labor market, which has created enormous job opportunities and attracted many rural-to-urban migrants to work in the cities. Second, the state’s promotion of the market economy coincides with the resurgence of a sex market that encourages the commodification of the body. This has provided an alternative way to earn quick and easy money, especially for migrant workers, who often hold the hardest and most underpaid jobs. Third, the state has made efforts to lessen control over private lives, especially homosexuality. This can be seen in the removal of hooliganism from the 1997 revised criminal law, and the removal of homosexuality from the Chinese Psychiatric Association list of mental illnesses in 2001. These changes have led to the emergence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (tongzhi) communities, which have long been suppressed, especially in rural areas, thereby providing an increased demand for male prostitution.

Social Control and Stigma of Male Prostitution

Male prostitution in China is mainly regulated by law and is stigmatized by both mainstream society and the gay community. The Chinese government has implemented an abolition model of prostitution since the Mao period. According to this model, third-party prostitution (organizing, inducing, introducing, facilitating, or forcing another person to engage in prostitution) is a criminal offense, punishable by a number of years’ imprisonment and possible fines. First-party prostitution is not criminalized but is regarded as socially harmful, with both prostitutes and their clients being subject to periods of reform detention, also with possible fines. The government has always implemented large-scale

yanda

(hard strike/stern blow) media campaigns and routine measures (raiding brothels, using undercover police to arrest prostitutes). These anti-prostitution measures targeted only female prostitutes until 2004, when a 34-year-old man named Li Ning from Nanjing was sentenced to jail for eight years and fined 60,000

yuan

for organizing male-on-male prostitution services. Since this widely publicized case (and similar cases), the government has tended to treat same-sex prostitution in the same manner as heterosexual prostitution (Jeffreys, 2007).

yanda

(hard strike/stern blow) media campaigns and routine measures (raiding brothels, using undercover police to arrest prostitutes). These anti-prostitution measures targeted only female prostitutes until 2004, when a 34-year-old man named Li Ning from Nanjing was sentenced to jail for eight years and fined 60,000

yuan

for organizing male-on-male prostitution services. Since this widely publicized case (and similar cases), the government has tended to treat same-sex prostitution in the same manner as heterosexual prostitution (Jeffreys, 2007).

The discussion of money boys in popular culture (such as newspapers

1

) and academic studies (Choi et al., 2002; He et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2008) is still dominated by pathological, public health, and moralist paradigms. These paradigms construct an image of young and innocent rural-to-urban migrants with little or no education who are totally unaware of the illegality of prostitution. Attracted to the large amounts of quick money that can be earned through sex work, these young men are lured by pimps and finally locked up in brothels and forced to have sex with clients, thus becoming vectors of sexual disease and victims of exploitative capitalism.

1

) and academic studies (Choi et al., 2002; He et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2008) is still dominated by pathological, public health, and moralist paradigms. These paradigms construct an image of young and innocent rural-to-urban migrants with little or no education who are totally unaware of the illegality of prostitution. Attracted to the large amounts of quick money that can be earned through sex work, these young men are lured by pimps and finally locked up in brothels and forced to have sex with clients, thus becoming vectors of sexual disease and victims of exploitative capitalism.

The social stigma surrounding money boys is not restricted to mainstream society; it is also prevalent in gay communities. Slowly dissociated from the pathological (mental patient) and deviant (hooligan) subjects, the new tongzhi identity has slowly emerged since the 1990s to form what can be seen as a derivative of global queer identity: urban, middle-class, knowledgeable, civilized, cosmopolitan, and consumerist (Altman, 1996, 1997). Although the tongzhi community provides positive cultural resources for gay men and lesbians, this new global queer identity sometimes serves less to enhance solidarity and identification than it does to divide and demarcate those who can fully access this ideal from those who cannot. Money boys are usually looked down on, due to their rural and provincial status (especially in Shanghai), and thus are seen as having low

suzhi

(quality). On top of this, they are charged with mixing sex with money and are thus seen as immoral. Finally, they are accused of corrupting the “good” image of largely middle-class gay men and are thus treated as “not respectable” (Rodney, 2005; Rofel, 2010). So money boys, among others (the poor, rural, HIV positive, nonmonogamous), are tongzhi outcasts who fail to fulfil the ideal of being a “good” homosexual (Kong, 2012).

suzhi

(quality). On top of this, they are charged with mixing sex with money and are thus seen as immoral. Finally, they are accused of corrupting the “good” image of largely middle-class gay men and are thus treated as “not respectable” (Rodney, 2005; Rofel, 2010). So money boys, among others (the poor, rural, HIV positive, nonmonogamous), are tongzhi outcasts who fail to fulfil the ideal of being a “good” homosexual (Kong, 2012).

FIGURE 13.3

A money boy in his flat in Beijing, China.

The Organization and Structure of the Male Sex Industry

Around the world there are many variations of men who sell sex (Aggleton, 1999; West & de Villiers, 1993). In China, money boys are mainly men in their early twenties, although middle-aged “bears” and male-to-female cross-dressers/transsexuals are common. There are four major occupational types. The first is the full-time independent operator who mainly works on his own and hustles in public areas like parks and bars or on the Internet. Sex normally takes place elsewhere (e.g., in hotels) after the details are negotiated. The second type is the full-time brothel worker, who usually works under an agent (a pimp or manager) in an indoor setting, such as a male brothel or massage parlor. The money boy usually lives at the venue and cannot go out without permission. Clients can choose boys, have sex and/or erotic massages in a cubicle inside the venue, or take them out for a few hours or even for an overnight stay elsewhere. The third type is the part-time or freelance worker, one who has quit the job but freelances occasionally when he is short of money or is requested by old clients. The final type is the

beiyangde

(houseboy), who is kept by a client.

beiyangde

(houseboy), who is kept by a client.

Other books

Never Eighteen by Bostic, Megan

Hermanos de armas by Lois McMaster Bujold

Twisted Tale of Stormy Gale by Christine Bell

Found: A Matt Royal Mystery by Griffin, H. Terrell

Locket full of Secrets by Dana Burkey

Lady Elizabeth's Comet by Sheila Simonson

A Quantum Mythology by Gavin G. Smith

Command Decision (Project Gliese 581g #1) by S.E. Smith

Theft on Thursday by Ann Purser

The Seduction of Sarah Marks by Kathleen Bittner Roth