Male Sex Work and Society (7 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

*

We have adopted the term “sex work” throughout this book to describe commercial sexual exchanges. We consider the term “prostitute” to be an ideological representation that stigmatizes people labeled as such. To address this, liberal factions of the feminist movement and sex industry advocates have sought to counter-construct the prostitute as sex worker, arguing that those involved in the sex industry are no different from other workers. This industrial or occupational focus has gained much currency since the 1970s, despite the categorical limitations of the term “sex worker,” which has become an umbrella concept for a range of behaviors, not all of which would traditionally be considered prostitution. While we have favored the term “sex worker” in this collection, prostitute/prostitution have been adopted when describing ideological representations of commercial sexual exchanges or when referring to historical examples. In this respect, we adopt a constructionist position with regard to the use of terminology.

We have adopted the term “sex work” throughout this book to describe commercial sexual exchanges. We consider the term “prostitute” to be an ideological representation that stigmatizes people labeled as such. To address this, liberal factions of the feminist movement and sex industry advocates have sought to counter-construct the prostitute as sex worker, arguing that those involved in the sex industry are no different from other workers. This industrial or occupational focus has gained much currency since the 1970s, despite the categorical limitations of the term “sex worker,” which has become an umbrella concept for a range of behaviors, not all of which would traditionally be considered prostitution. While we have favored the term “sex worker” in this collection, prostitute/prostitution have been adopted when describing ideological representations of commercial sexual exchanges or when referring to historical examples. In this respect, we adopt a constructionist position with regard to the use of terminology.

Mack Friedman reminds us that evidence of same-sex eroticism can be found across history and cultures. When the old cliché about prostitution being the world’s oldest profession is rattled out, we tend to think of females rather than males. However, there is evidence that male and female prostitution have coexisted throughout history. In fact, male prostitution was so entrenched in Rome that male sex workers had their own holiday and paid a tax to the state. Yet Friedman shows how the meanings and values associated with male sex work have varied considerably in various cultural and historical contexts. In the ancient world, for example, those playing dominant same-sex erotic roles had elevated social status

.

.

It is probably safe to say that power and hierarchy have always been influential in the world of sex work, yet recent research has found clear evidence that some of these encounters evolved into romance and love at various historical junctures. A similar point is made in

Touching Encounters,

the 2012 book by Kevin Walby, which states that, rather than all such exchanges being merely sexual or commercial encounters, an authentic romantic relationship can develop between client and escort. Male sex work is indeed about power and commerce, but it also involves friendship and mutuality. The real psychosocial nature of male sex work is waiting to be fully researched, explained, and shared with the world

.

Touching Encounters,

the 2012 book by Kevin Walby, which states that, rather than all such exchanges being merely sexual or commercial encounters, an authentic romantic relationship can develop between client and escort. Male sex work is indeed about power and commerce, but it also involves friendship and mutuality. The real psychosocial nature of male sex work is waiting to be fully researched, explained, and shared with the world

.

When we look at male sex work, we must look at the two primary actions that comprise this event. First there is sex, most commonly between an older and a younger male. Then there is a reward for this sex, some kind of payment beyond a simple show of gratitude. Male sex work almost always has been viewed as a consequence and reflection of economic disparity between older and younger partners, and has existed across a wide continuum of cultural acceptance. Conditions for male sex workers are contingent, as we will see throughout this book, not only on the degree of cultural acceptance afforded them but on the degree of cultural acceptance afforded any sexual activity between men.

The history of male sex workers is gaptoothed and disjointed, like an aging boxer. Here, a note of caution: there is no canon to draw from, and your correspondent is not a trained historian. In other words, there is no “sex work” field, and if there were, I am sure I would not be the best fielder. This chapter is comprised of historical snapshots and a brief analysis of global hustler history, based primarily on the work of amateur and professional classicists and historians. It centers on what we can infer about the cultural conditions of male sex work in ancient Greece and Rome, pre-modern and Renaissance Europe, Japan in the days of the samurai, colonial and industrial America, and

fin de siècle

Western societies.

fin de siècle

Western societies.

Greek

Pornos:

Timarkhos on Trial

Pornos:

Timarkhos on Trial

In 346 BCE, the city-state of Athens signed a peace treaty with Macedonian warmonger Philip II via the envoys of the Athenian assembly. Philip II did not initially honor this treaty, however, for which the Athenian assembly blamed the envoys and attempted to court-martial them. One renegade envoy, Aiski-nes, strategically preempted the assembly by prosecuting Timarkhos, an assemblyman who was, not coincidentally, helping the Athenian assembly prepare to prosecute the envoys. Aiskhines took Timarkhos to court for having violated a law by merely addressing the assembly. According to Aiskhines, Timarkhos had been a prostitute in his youth and thus was barred from speaking to the Athenian assembly. Greek historian Kenneth J. Dover’s interpretation of that law is that it

debarred from addressing the assembly, and from many other civic rights, any citizen who maltreated his parents, evaded military service, fled in battle, consumed his inheritance,

or prostituted his body to another male

; this law provided for the denunciation, indictment, and trial of anyone who, although disqualified on one or other of these grounds, had attempted to exercise any of the rights forbidden to him.

1

The audacity of Timarkhos, to address the assembly after having conducted sex work! Although we might view ancient Greek culture as sexually permissive, especially of sex between males, an intricate set of sociosexual codes delimited these relationships. These codes further distinguished between relationships for love, tutelage, and mentorship, and those that strictly involved lust and financial gain. Along with fairly high parity between younger and older male citizens in Greek society was great tolerance for affairs intertwining the stated characteristics, so long as they existed within gender norms. Younger and older males were linguistically separated within their relationships, subject to differentiation by both age and desire. The younger males were termed

pais

, which, according to Dover, is “a word also used for ‘child,’ ‘girl,’ ‘son,’ ‘daughter,’ and ‘slave.’”

2

This curious conflation of meanings makes pais synonymous with, in this case, “one who is passive.” The older partner was, by contrast, active or passionate. This relativity of passion was further connoted by the conjugation of

eros

, or love. The masculine noun

erastes

defined the “senior partner,” the man who is the lover, whereas the pais was also called

eromenos

, a masculine passive participle that meant “beloved.”

3

pais

, which, according to Dover, is “a word also used for ‘child,’ ‘girl,’ ‘son,’ ‘daughter,’ and ‘slave.’”

2

This curious conflation of meanings makes pais synonymous with, in this case, “one who is passive.” The older partner was, by contrast, active or passionate. This relativity of passion was further connoted by the conjugation of

eros

, or love. The masculine noun

erastes

defined the “senior partner,” the man who is the lover, whereas the pais was also called

eromenos

, a masculine passive participle that meant “beloved.”

3

This is not the transactional sex of contemporary American paradigm. Rather, it was seen as a humanistic dyad that rewarded both parties, fulfilling such basic needs as education, affection, attention, and sex. Greek scholar Thomas Martin writes that

[pederasty] was generally accepted as appropriate behavior, so long as the older man did not exploit his younger companion purely for physical gratification

or neglect his education in public affairs

.

4

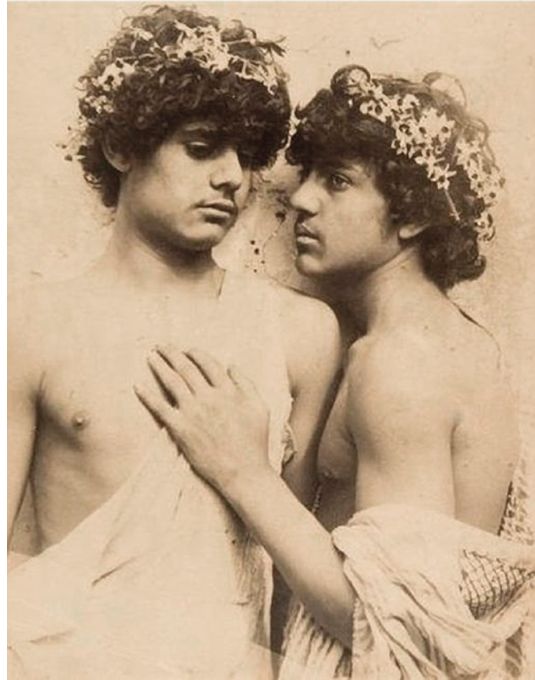

FIGURE 1.1

Wilhelm Plüschow (1852-1930) was an aristocrat and artist who produced homoerotic photographs in Italy. This is his portrait of his rumored lover, Vincenzo Galdi (right), with “Edoardo” at Posillipo, Naples, before 1895.

What happened, then, when a senior partner exploited his younger charge, using him solely for sexual release and neglecting his education? In Classical Greece, this was no longer

paederastia

but

porneia:

strictly prostitution. Compare this to the “sugar daddy,” an imperfect contemporary corollary; when a sugar daddy neglects his kept boy’s social education and professional development, the relationship becomes nothing more than a hustle.

paederastia

but

porneia:

strictly prostitution. Compare this to the “sugar daddy,” an imperfect contemporary corollary; when a sugar daddy neglects his kept boy’s social education and professional development, the relationship becomes nothing more than a hustle.

Greek usage of the word “porneia” slowly evolved from “an originally precise term for a specific type of sexual behavior to all sexual behavior of which they disapprove and even to non-sexual behavior which is for any reason unwelcome to them … In later Greek [porneia] is applied to any sexual behavior towards which the writer is hostile.”

5

This etymology characterizes the first distinct Western word for male prostitution: porneia. When set apart from pederasty, porneia came to connote an unnatural, undesirably exploitive quality for the senior partner, while impugning the junior partner with a nasty mercenary aspect. We can see this in the Grecian typology of female sex workers between

porne

and

hetaira

, or prostitute and mistress. Dover argues that although “the dividing line between the two categories could not be sharp … whether one applied the term

porne

or the term ‘hetaira’ to a woman depended on the emotional attitude towards her which one wished to express or to engender in one’s hearers.”

6

Dover uses the writer Anaxilas as an example, citing a passage wherein

hetairai

(plural of hetaira) are defined by loyalty and affection and

pornai

(plural of porne) by avarice and deception.

7

Male prostitutes also were differentiated from being

eromenoi

by more than just semantics and the level of social approval; they were institutionally distinguished by the laws that upheld Greek culture. One could say that male prostitution was tolerated and decriminalized, but Grecian male prostitutes were often denied basic citizenship rights.

5

This etymology characterizes the first distinct Western word for male prostitution: porneia. When set apart from pederasty, porneia came to connote an unnatural, undesirably exploitive quality for the senior partner, while impugning the junior partner with a nasty mercenary aspect. We can see this in the Grecian typology of female sex workers between

porne

and

hetaira

, or prostitute and mistress. Dover argues that although “the dividing line between the two categories could not be sharp … whether one applied the term

porne

or the term ‘hetaira’ to a woman depended on the emotional attitude towards her which one wished to express or to engender in one’s hearers.”

6

Dover uses the writer Anaxilas as an example, citing a passage wherein

hetairai

(plural of hetaira) are defined by loyalty and affection and

pornai

(plural of porne) by avarice and deception.

7

Male prostitutes also were differentiated from being

eromenoi

by more than just semantics and the level of social approval; they were institutionally distinguished by the laws that upheld Greek culture. One could say that male prostitution was tolerated and decriminalized, but Grecian male prostitutes were often denied basic citizenship rights.

Other books

Can't Stand the Heat by Shelly Ellis

Nice Girls Don't Bite Their Neighbors by Molly Harper

Ronicky Doone's Treasure (1922) by Brand, Max

The Ruby Locket by Anita Higman, Hillary McMullen

The Marquis by Michael O'Neill

Escape by Korman, Gordon

The Devil's Lair (A Lou Prophet Western #6) by Peter Brandvold

Garnet's TreasureBN.html by Hart, Jillian

Cyberella: Preyfinders Universe by Cari Silverwood

The House Of The Bears by John Creasey