Malinche (6 page)

Authors: Laura Esquivel

His eyes would breakfast on wind and light that morning. The violent gusts shook the curtains, ripped things from their place, and cast objects onto the floor of the room where Montezuma had slept. Horror overcame the leader and his mind fabricated at great speed a series of images of exemplary punishments: agave thorns piercing the tongue, or the penis, bloody needles that spoke of guilt, of the great guilt that Montezuma bore on his shoulders because his people, the Aztecs, had betrayed and distorted the principles of the ancient Toltec religion.

The Aztecs had been a nomadic people until they established themselves in Tula. The mythic founder of Tula was Quetzalcóatl, the Plumed Serpent, and Montezuma was sure that the arrival of the Spanish was due to the fact that Quetzalcóatl had returned and was coming to get his due. Fear of the god's punishment paralyzed his enormous skill for war. Otherwise, he would have wiped out the foreigners in a single day.

I

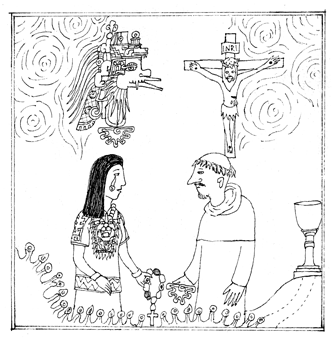

t was the middle of spring when they baptized Malinalli. She was dressed all in white. There was no color on her dress, but a great deal of embroidery. She knew the value of embroidery, of spinning thread and the art of feathers, and had chosen for the occasion a ceremonial

huipil,

full of meaning, that she herself had made.

The

huipiles

spoke. They said much about the women who had made them. They spoke of their time, their social condition, their marital state, their connection to the cosmos. Putting on a

huipil

was a whole initiation; in doing so one repeated daily the voyage from the interior to the exterior. On putting one's head through the opening of the huipil, one moved from the world of dreams, which was revealed in the embroidery, into everyday life, which appears when the head comes out. This awakening to reality is a ritual morning act that reminds us day after day of the significance of birth.

Huipiles

keep one's head centered, with the rest of the body covered in the front, in the back, and on both sides. The cross that is formed by the embroidered parts of the

huipil

means that one is planted in the center of the universe, lit by the Sun and covered by the Four Winds, the Four Directions, the Four Elements. That's how Malinalli felt in her beautiful white

huipil

as she was ready to be baptized.

For her the ritual of baptism was very important, and she was deeply moved to know that it was the same for the Spaniards. Her ancestors performed it according to their own customs. Her grandmother performed it for her after she was born, and it was assumed that at the age of thirteen it needed to be done for her again, but no one did it. Malinalli very much regretted it.

The number thirteen was very significant. Thirteen were the moons in a solar year. Thirteen menstruations. Thirteen, the houses of the sacred calendar of the Mayans and the Mexicas. Each of its houses was made up of twenty days and the sum of thirteen houses, each with twenty days, came to a total of 260 days. When one was born, both the solar calendar of 365 days and the sacred one of 260 days began and did not join again until the fifty-second year, a complete cycle that would begin again. If you add five and two, the numbers in fifty-two, you get seven, which is also a magic number because seven are the days that make each of the four lunar phases. Malinalli knew that the first seven days, when the moon was between the Earth and the Sun, the Moon is dark, for the new moon is on the verge of rising, and this was a time to be silent so that all things that had yet to be born would do so freely, without any interference. It was the best time to “feel” what should be the main objective of the actions one would undertake during the coming lunar cycle. It was the birth of purpose. The next seven days, when the moon rose at noon and fell at midnight, showing only half her face, was the time to put one's purposes into action. The next seven days, when the Moon was on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun, and shone in fullness over the earth, was the time to celebrate and share our achievements. And the last seven days, when the Moon showed the other half of her face, was a time to reflect on everything gained over those twenty-eight days.

All these aspects of time accompanied each human being from the moment of birth. Malinalli had been born in the twelfth house. The date of birth marked one's fate and because of this Malinalli bore the name of the house in which she was born. The meaning of the number twelve is resurrection. The glyph that corresponds to the number twelve is a skull in profile, for it represents all that dies and is transformed. Growing out of the skull instead of hair is

malinalli,

a fiber also known as sacred grass. The glyph for twelve alludes to death, which embraces her dead son and offers him rest. It represents either unity or a mother who snatches from death the bundle of a corpse wrapped in its shroud and bound with

malinalli,

the sacred grass. She takes him to return him to the unity of the One and give birth to him, renewed.

Malinalli

was also the symbol of the town, as well as of the bewitching city of Malinalco, founded by the terrestrial-lunar goddess MalÃnal-Xóchitl, or flower of

malinalli

.

Curiously, it was the fiber

malinalli

that was used to make the poncho which Juan Diego was wearing in the year 1531, when the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared to him supported by the moon, on the twelfth day of the twelfth month, and twelve years after Hernán Cortés had arrived in Mexico.

Malinalli was so proud of all these concepts contained in the meaning of her name that she tried to give form to them in the

huipil

that she had begun to embroider several moons earlier.

It was during the time of silence that she had felt the need to make it, and until now she had believed that it was the proper thing to do. The

huipil

was the one that she chose to wear in the longedâfor ceremony of baptism. Made with cotton thread that she herself had spun and woven in a loom, it had been appliquéd with seashells and precious feathers. The symbol for the moving wind was embroidered on the chest, surrounded by plumed serpents. It was in itself an encrypted message to be seen and appraised by the emissaries of Lord Quetzalcóatl. She was dressed like a faithful devotee, but no one seemed to notice. The only one who seemed to be dazzled by her attire was a horse that drank from a nearby river and that never took its eyes off her throughout the whole baptismal ceremony. Malinalli did not fail to notice and from then on a loving relationship developed between them.

After the ceremony ended, Malinalli approached Friar Aguilar, to ask him about the meaning of Marina, the name they had just given her. The friar responded that Marina was she who came from the sea.

“Is that all?” Malinalli asked.

The friar responded with a simple, “Yes.”

The disappointment must have been evident in her eyes. She was hoping that the name granted to her by the emissaries of Quetzalcóatl would have a deeper meaning since, as she assumed, it wasn't being granted to her by simple mortals who were completely ignorant of the profound meaning of the universe, but by initiates. Her name had to mean something important. She persisted with the friar, but the only additional answer that she could get from him was that they had chosen the name because Malinalli and Marina shared a certain phonetic similarity.

No. She refused to believe it. But because it was such a momentous day in Malinalli's life, she did not let herself sink into disappointment, but instead decided on her own to take control of her new name. If her native name meant braided grass, and if the grass and all plants in general needed water, and her new name was related to the sea, it meant that she was assured of eternal life, for water was eternal and it would forever nourish who she was: the braided grass. Yes, that was exactly the meaning of her new name!

She wanted to pronounce it right away but found it impossible. The “r” in Marina got stuck on the tip of her tongue and the most that she could accomplish, after a few attempts, was to utter “Malina,” which left her very frustrated.

One of the things that most amazed her was that with the same oral apparatus, human beings were capable of emitting an infinite amount of different sounds. And she, who considered herself a great imitator, could not understand why she could not pronounce the “r.” She asked Aguilar to pronounce her new name, time and again, and she did not take her eyes once from the friar's lips, who patiently repeated “Marina” again and again. It became clear to Malinalli that what was needed to pronounce the “r” was to place her tongue behind her teeth for only a moment, but her tongue, up against her palate as she was used to, could not move quickly enough and the results were disastrous. It was obvious that she would need a lot of practice, but she was not ready to give in.

Ever since she was a girl, she had been able to use her tongue to replicate any sound. When she was one, she had loved to babble, to make noises and little bubbles of saliva with her mouth, to imitate any sound that she heard. She paid great attention to the songs of birds, to the barking of dogs. Surrounded by the silence of the night, she liked to discover distant noises and identify the animal that was emitting this or that sound so that she could later imitate it. Until the arrival of the Spaniards, her method of learning had been very effective, but the new language had brought to her life new and complicated challenges.

Wanting to try another word so that she would not feel so frustrated, she decided to ask the friar about his god. She wanted to know everything about him: his name, his qualities, how she might approach him, to speak to him, to celebrate him, to worship him. She had loved listening to the sermon before the baptismâwhich Aguilar himself had translated for themâin which the Spaniards had asked that they no longer be fooled by false gods who demanded human sacrifice. They said that the true god, whom they brought with them, was good and loving and would never demand such a thing. In Malinalli's eyes, that merciful god could be none other than the Lord Quetzalcóatl, who in new garments was returning to these lands to reinstate his kingdom in harmony with the cosmos. She wanted to welcome him, to speak to him.

She asked the friar to teach her how to pronounce the name of their god. Aguilar kindly complied and Malinalli, overcome with emotion, realized that the word, not having any “r”s in it, did not present a problem at all. Malinalli clapped her hands like a young child. She was delighted, thrilled by the sense of belonging that she felt when able to pronounce the name that another social group had assigned to something. It filled her with joy, for nothing disturbed her more than the feeling of being excluded. Right away, Malinalli asked the friar the name of the god's wife. Aguilar told her that he had no wife.

“But then, who is that lady with the child in her arms whom you place in the temple?”

“She is the mother of Christ, of Jesus Christ, who came to save us.”

She was a mother! The mother of them all, and so she had to be the lady Tonantzin. It was no coincidence that when the friar had celebrated the mass before the baptism, Malinalli felt enraptured by a feeling that she could not understand. It was a sort of nostalgia for the maternal arms, a longing to feel enveloped, embraced, sustained, and protected by her mother, as at one time she must have been; by her grandmother, as she definitely had been; by Tonantzin, as she hoped she would be; and by a universal mother, like that white lady who held the child in her arms. A mother who wouldn't give her away, who wouldn't let her go, who wouldn't let her fall to the ground but would raise her to the sky, offer her to the four winds, allow her to recover her purity. All these thoughts kept her company as the Spanish priest said Mass in a language that she did not understand, but could imagine.

Like Malinalli, Cortés also thought about his mother, and the countless times she had led him by the hand to church to pray for the health of her sickly child. She was constantly preoccupied with helping overcome his shortness, his physical weakness, and his condition as only child. It was clear that in a society dedicated to the art of war and in which street fights were common, a boy with these characteristics was destined for failure, and perhaps because of this his parents had made sure they provided him with a good education.