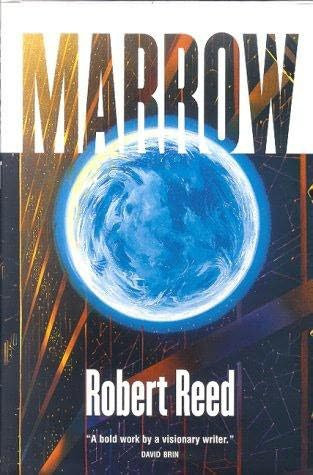

Mallow

Book Jacket

Science Fiction, Novel

The Ship has travelled the universe for longer than any of the near-immortal crew can recall, its true purpose and origins unknown. Larger than many planets, it houses thousands of alien races and just as many secrets. Now one has been discovered: at the centre of the Ship is a planet: Marrow.

Robert Reed is the author of more than half a dozen SF novels, as well as a multitude of short stories appearing in major magazines and best-of-the-year anthologies. The first Grand Prize Winner of the Writers of the Future contest, he has written a number of stories that have been finalists for the Hugo and Nebula Awards. He lives in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Find out more about Robert Reed and other Orbit authors by registering for the free monthly newsletter at

www.orbitbooks.net

By Robert Reed

marrow the well of stars

sister alice

down the bright way

ROBERT REED

orbit

MARROW

ORBIT

First published in Great Britain by Orbit 2001 Reprinted 2002,2004, 2005, 2007

Part of this novel appeared in substantially different form in Science Fiction Age, July 1997 issue. Copyright © by Robert Reed

Copyright © 2000 by Robert Reed

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All characters and events in this publication are fictitious ami any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A C1P catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-84149-078-6

Papers used by Orbil are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests and certified in accordance with the rules of the Forest Stewardship Council.

Typeset in Bembo by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Polmont, Stirlingshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham pic Paper supplied by Hellefoss AS. Norway

Orbit An imprint of Little, Brown Book Group Brcttcnham House

Lancaster Place London WC2E 7EN

A Member of the Hachette

Livre Group of Companies

To the first artist in my life, My grandfather, Quentin 'Heinz' Moore

THE

SHIP

. . . a sleep, sweet

as Death . . . time traversed, and an incalculable distance . . . and then a splash of light emerged from the dark and the cold, i

ts warm

ing touch slowly explaining itself to me, showing suns and little worlds and great swirls of colored gas and angry, roaring dust.

A barred spiral galaxy, this was.

Possessing such beauty, and a majesty, that I

could not help but stare. And w

rapped within that majesty, a frailty, ignorant and vast.

Th

e galaxy's path and mine were plain. Without question, we would collide.

My gaze was sure to be returned by many more gazes.

1

knew that, just as I had known that this day was inevitable. Yet when I saw that tiny first machine racing toward me, I was surprised. So soon! And yes, the machine could see me. I watched its mirrored eyes focus on my scarred old face. I watched it fire tiny rockets, exhausting itself in

order to pass nearer to me. Th

en it spat out a minuscule device whose only duty was to collide with my face, undoubtedly followed by a trail of data and new questions. At nearly half the speed of light, we met.

Only I survived. Th

en the mother machine swept past, turning its eyes, watching my trailing face, a part of me imagining its wondrous surprise.

My backside is adorned with rocket nozzles.

Bigger than worlds, and more ancient, my engines are as chilled and quiet as this ancient universe of ours.

Hello, I said.

Without a voice.

Brother machine, hello.

My friend continued on its way, and for a little while, I was alone again. Winch was when I first sensed just

how deep my loneliness had grown

.

Ignoring caution, denying every duty, I began

wishing for another visitor. What would be th

e harm?

A

little

robotic companion, transitory

and incompetent . .

. how could a mere device pres

ent any hazard to me . . . ?

But it wasn't one probe sent to greet me. No, the machines came in flocks and fleets. Some serenely committed suicide, diving into my leading face. Others flew near enough to feel my tug, curling around my backside, enjoying a close qui

ck took at my great engines. Th

eir shape and basic design were the same as the first probe, implying a shared maker. Following their trajectories back through space and time, I discovered a tell

-

tale intersection.

A

single yellowish sun lay at the nexus. It and its neighboring suns had spawned the machines. I slowly accepted the unlikely answer that a single species had seen me before any other. But clearly, this galaxy was not a simple place. As time passed and the intervening distances shrank, other devices arrived from a multitude of

places. I watched a parade of machines built of simple metals and sculpted gas and encased in hydrogen ice, and from hundreds of thousands of suns came every sort of electromagnetic noise, in soft squirts and squawks, elaborate songs and brazen shouts.

'Hello,' the voices shouted. 'And who are

you, friend?' Wh

o I appear to be, I am. 'And wha

t, friend, do you mean to us?' J

ust what I appear to mean, I told them. With silence. In every way, what you sec in me is most definitely what I am.

A

nimals came from

someplace between me and that yellowish sun.

Th

eir first vessel was tiny, and simple, and extraordinarily frail. Enormous bravery must have taken them this far. 'Die creatures had to leave the brightness of their own galaxy, and at mid-voyage, they stopped themselves, turned and started home again, their little engines pushing and pushing, matching my terrific vel

ocity at the perfect moment. Then

they slowed again, just slightly, letting me catch up to them, and maintaining a smart cautious distance, they coaxed themselves into a useful orbit.

As I watched, a thousand automated machines descended on me.

Hovered, then set down.

My scars and my trajectory implied my age.

No galaxies lay behind me. Not even a dark, half-born galaxy of consequence. Tliat kind of emptiness has few obstacles. Comets are rare, suns rarer, and even simple dusts are scarce. Yet my leading face was cratered and cracked, implying to the curious animals that I had come a terrific way, and I was as old as their home world.

At the very least.

'Thi

s ship is cold,' their machines reported. 'Most definitely asleep, and quite possibly dead.' A derelict, in simple terms.

Between my leading face and the trailing face lay great ports, empty and closed, and securely locked. But smaller hatches

and doorways could be opened wi

th a determined push, and after begging for instructions, that wa

s what several machines did. Th

ey eased open doors that had been closed almost forever, and behind them they found descending passageways and neat, unworn stairs perfectly suited for a humanoid's graceful, long-legged gait.

The animals themselves made their last little leap.

Whe

n feet had last descended my stairs, I could not recall.

But here came the humans, in tw

os and tens, entering my interior with a cautious sense of purpose. At first, they wore bulky suits and carried weapons and spoke in soft radio voices, using elaborate codes. But as they moved deeper, the old air thickened around them, and tests showed oxygen left to breathe, a multitude of life-support systems still at work, coaxing my guests to remove their helmets, sniffing once, then breathing deeper, and in that human fashion, smiling.

Th

e first voice said, 'Hello,' and heard only its own nervous echo in reply.

Beneath my armored hull was a vast cold ocean of stone laced with grand passageways

and abrupt dead ends and rooms t

oo vast to be absorbed in a sing

le look, or even a lifetime. Th

e darkness was thorough, relentless. But every wall and ceiling had its lamps and holoprojectors, their machinery transparently simple and easily ignited; plus there were armies of local reactors waiting to be brought from their slumber modes to furnish power.

In little places, then larger ones, I was awakened.

And still, I had no voice.

Did I ever possess the power of speech?

Perhaps not, I realized. Perhaps what I remember as my voice is actually another's. But whose? And how can any span of time rob such a basic, essential knowledge?

Most of the humans now boarded me.

With care and fondness, I counted them. Twelve to the fo

urth power, plus a few more. Wh

ich was a tiny, almost negligible number compared to my vastness.

But then more ships arrived — an armada coming from oth

er suns, other human worlds. These new

er vessels had more powerful, efficient engines. And I realized that even if these were animal

s, they could adapt quickly. Wh

ich had to be a good thing.

But why was it good?

With all of my new energies,

I

tried to shout at my innocent companions, begging them to please listen to me. Yet I was mute.

Save a whispering wind, and the crackle

if

random energy in a granitic wall, and the dry clatter of gravel preceding the touch of a human foot, I could make no sound.

Th

e human population increased another twelvefold.

And for a little while after that, nothing changed.

Th

e explorers had all arrived. With a crisp efficiency, they mapped every tunnel and crevice, giving each a precise designation

Every large room and cavernous chamber was honored with a special name. Great seas of water and ammonia, methane and silicone, were found in my interior, at many depths. Banks of machinery could manipulate their chemistry, making them suitable for a wide range of life-forms. Understandably, the humans adjusted one of the water seas as an experiment, its salts and acidity made to their liking, its temperature warm on the surface and cold beneath; and with a bid toward permanence, they built a little city overlooking the sea's black-bouldered shore.

Wh

atever the humans discovered inside me, I discovered, too.

Until that moment, I had never fully comprehended my greatness, or my own glorious, well-worn beauty.

I wanted to thank my guests, and could not. Just as I couldn't make them hear my plaintive warnings. But I was growing more comfortable with my muteness. Everything has its reason, and no matter how great and glorious I am, I am nothing compared to the wise ones who created me . . . and who am I, a mere machine, to question their boundless wisdom . . . ?

Beneath my watery

seas were still larger oceans of liquid hydrogen.

Fuel for my sleeping engines, no doubt.

Humans learned how to repair my pumps and giant reactors, and they managed to activate one of the great engines, an experimental burst of high-velocity plasmas proving hotter than expected, and more powerful.

By then, we were plunging into their galaxy.

It was named for a mother's secretions, this Milky Way.

I

began to taste its dusts, and its feeble heat warmed my old skin. A quarter of a trillion suns were below me, plus a hundred tri

llion worlds, living and otherwi

se. From nothingness, I was falling into the cosmopolitan heart of the universe. Tens of thousands of species had seen my arrival, and naturally a few sent their own tiny ships, orbiting me at the usual respectful distance, using many voices as they asked to be allowed onboard, or bluntly demanded to be given possession of me.

The humans refused everyone. Politely at first, then less so.

I heard their cold officious words about interstellar law and t

he status of derelict ships. Th

en came a careful, calculated silence.

One of the interlopers decided on action. Without warning, it attacked, turning the human starships into light and pulverized debris.

Unprepared for war, most species made a graceless retreat. Only the most violent few remained, unleashing their weapons against

my armored hull. But if I can w

ithstand a giant comet impacting at a fat fraction of lightspeed, their tritium bombs and X-ray laser

s could do nothing. Nothing. Th

e humans, safely inside me, went about their lives, ignoring the bombardment, repairing and recalibrating my old guts while their enemies exhausted themselves against my great body.

One after another, the starships gave up the fight and left for home.

Desperate to establish any claim, the last speci

es attempted a hard landing. Th

eir captain plunged toward my leading face, dipping in and out of craters while streaking toward the nearest port. It was a brave and bold and foolhardy act. A network of shield generators and lasers and antimatter cannons lay inside deep bunkers. In some lost age, they must have worked to protect me from comets and other hazards. As they had with my other systems, the humans had discovered the machinery and made repairs. And with a mixture of retribution and charity, they used the lasers to destroy the attackers' engines, and their weapons, and they made prisoners out of the survivors.

Th

en with a roaring voice, they shouted at the Milky Way.

'This

ship is ours!' they shouted.

'Ours!'

'Now, and always! Th

e Ship belongs to us . . . !'

***

S

et on top

of a great black boulder were black wooden chairs, and sitting on those chairs, enjoying the false sunshine, were the Master Captain and her closest staff, each dressed in his or her fanciest mirrored uniform.

'Now that we've won,' began the Master, 'what have we won?'

No one spoke.

'We've got title to the largest starship ever,' she continued, gesturing at a blue ceiling and the warm su

r

f and the warmer basaltic rock. 'But governments and corporations paid for our mission here, and they aren't unreasonable to expect some return on their fat investments.'

Everyone nodded, and waited. They knew the Master w

ell enough to hold tight to their opinions, at least until she looked at them and said their names.

'This ship is moving aw

fully fast,' she pointed out. 'Even if we could rotate one hundred and eighty degrees and fire its engines until the tanks are dry, we'd still be moving too fast to dock anywhere. You can't make twenty Earth masses dance for you. Can you?'

Silence.

She chose a narrow, coolly professional face. 'Miocene?' Her assistant said, 'Yes, madam.' 'Ideas? Any?'

'We can't stop ourselves, madam. But we could use our engines to adjust our course.' Miocene was a tall, perpetually calm woman. She glanced at the compad on her lap, then let her walnut-colored eyes lift and meet the Master's impatient gaze. 'Tiiere is a white dwarf ahead of us. A three-day burn starting now would take us past it at relatively close range, and instead of slicing through the galaxy, we would be turned.

The

ship would pass through human space, then continue on into the heart of the galaxy.'

'But to what end?' asked the Master.

'To give us more time to study this technology. Madam.'

A few of her fellow captains risked little nods of agreement.

Bui for some reason, the Muster wasn't convinced. With a sharp creaking of wood, she rose to her feet, towering over even the tallest of her subordinates. For a long while, she did nothing. She let the

m watch as she did nothing. The

n she turned and stared across the open water, studying the wind-driven waves as they broke against the basalt, her colorless swift mind trying to distill what was best from everything that was possible.

Out in the surf, a whale appeared.

It was a tailored minke whale

-a

popular species on terraformed worlds — and riding the saddle on its dark broad back was a single child. A girl, judging by her build and the wind-thinned giggle.

Quietly, the Master asked, 'Who

se child is that?'

With the war finished, the captains and crew had produced the occasional child, setting roots deeper into the ship.

Miocene rose and squinted at the bright water, then admitted, 'I'm not sure about the parents. But the girl lives nearby. I'm sure that I've seen her.'

'Get her. Bring her to me.'

Captains are captains because they can accomplish any chore, and usually with a minimum of fuss. But the girl and her whale proved difficult to catch. She ignored the order

s coming across her headset. Wh

en she saw the skimmer approaching, she gave a loud giggle, then made her friend dive, both us

ing their hydroliz

ing gills to breathe, staying out of easy reach for another full hour.

Finally a parent was found, then convinced to coax his daughter to the surface, where she was captured and dressed in an oversized robe, her long black hair dried and tied before she was ushered to the top of the great boulder.

Th

e Master rose, offering her cap

tive her own enormous chair. Th

en she sat on a knob of basalt, her mirrored uniform brilliant in the afternoon light, her voice almost as friendly as it was firm.

'Darling,' she asked, 'why do you ride that whale?'

'For fun,' the youn

g

ster replied instantly.

'But swimming is fun,' the Master countered. 'You can swim, can't you?'

'Better than you, ma'am. Probably.'

Wh

en the Master laughed, everyone else did as well. Except for Miocene, who watched this interrogation with a growing impatience.

'You'd rather ride than swim,' the Master said. 'Am I right?' 'Sometimes.'

'Whe

n you're clinging to your friend, do you feel safe?' 'I guess. Sure.'

'Safe.' Th

e word was so important th

at it needed to be repeated. Th

e Master said it a third time, then a fourth. Then again, she looked at the girl, smiled, and told her, 'Fine. Thank you. Go on off and play some more, darling.'

'Yes, madam.'

'By the way. Wh

at's your name?' 'Washen.'

'You

're a beautiful young woman. Th

ank you, Washen.' 'For what?'

'For your help,

of

course,' the Master purred. 'You've been absolutely vital.'

Everyone was puzzled. Th

e captains watched the girl walk away in that careful,

slow

way that children use when they know they are being watched. But before Washen

had gone, Miocene blurted, 'Wh

at does all this mean, madam?'

'You know perfectly well. Interstellar travel is less than safe.' A broad, bright grin spread across the Master's golden face. 'Even our largest, most durable starship can be obliterated by a chunk

of

nothing no larger than my fist.'

True,

of

course. Always.

'But inside this great ship, the passenger is perfectly safe. Today and forever, she is protected by hundreds

of

kilometers

of

high-grade hyperfiber, and protected by lasers and shields, and served by a cadre

of

th

e finest captains anywhere.' Th

e Master paused for an instant, enjoying the

drama. Th

en speaking over the rumble of the surf, she announced, 'We are going to sell passages on this great ship. Passages for a journey around the galaxy — a journey like no other — and every wealthy customer will be welcome. Human, alien, or machine!' Suddenly, the wind gusted.

Th

e Master's empty chair was pushed over on its side.

A dozen captains fought for the pri

vilege of righting the chair, w

hile Miocene, knowing what was best,

joined the Master instead, bow

in

g and smiling as she said, 'Wh

at a fine and perfect and wonderful idea . . . madam . . . !'

One

Washen was a

captain of consequence.

Fashionably tall, with an ageless strong body, she possessed handsome features wrapped around wise chocolate eyes. Her long obsidian hair was worn in a sensible bun, streaked with just enough white to lend authority. She conveyed a sense of easy confidence and relaxed competence, and with a little look or a gentle word, she lent her confidence to whoever deserved it. In public, she wore her mirrored captain's uniform with a regal bearing and

gentle

pride. Yet she had the rare gift of keeping others from feeling jealous of her station or intimidated by her presence. And even rarer was Washen s talent for embracing the instincts and customs of truly alien species, which was why, at the

M

aster Captains insistence, one of her duties was to greet their strangest passengers, explaining what

the strip

was and what it expected from its cherished guests.

Her day, like so many days, began at the bottom of Port Beta.

Washen adjusted the tilt of her cap, then gazed upward, watching as a kilometer-long taxi was lowered from the airlock. Stripped of its rockets, the bulky fuel tanks, and wide armored prow, the taxi resembled a great needle. Its hyperfiber hull glittered in the port's brilliant lights as skilled mates and their AIs controlled its descent with hair-thin cable and squid-limbs, bringing it down with the smoothness of a descending cap-car.

Which was a mistake. Through an implanted nexus, Washen called for the mates' boss. 'Let it drop,' she advised. 'Right now.'

An ice-white human face grimaced.

'But madam . . . ?'

'Now,' she demanded. 'Let it fall on its own.'

A captain's word weighed more than any mates caution. Besides, the taxi's hull could absorb much worse abuse, and both of them knew it.

With a low crackle, the squid-limbs pulled free.

For an instant, the needle seemed unaffected. Then the ship's gravity — much more than earth-standard - took hold and yanked it down into the cone-shaped berth reserved for it. The impact was jar

ring, but muted by the hyperfibe

r floor and a heavy dose of antinoise. Washen felt the collision in her toes and knees, and she let herself smile for a moment, imagining the passengers' delicious surprise.

'I need to fill out an accident report,' growled the white face.

'Naturally,' she replied. 'And I'll accept all the blame you can give me. Agreed?' 'Thank you . . . Captain . . .' 'No. Thank you.'

Washen strolled toward the berth and taxi, her smile fading, replaced with a theatrical grimness appropriate to this job.

The passengers were disembarking.

Flounders, they had been dubbed.

At a glance, Flounders resembled thick woolly rugs carried on dozens of strong and very short legs.They came from a superterran world, accustomed to five times the port's gravity, and like many species from such worlds, they demanded a thicker, richer atmosphere than what they found here. Implanted compressors aided their quick, shallow breathing. Pairs of large, eerily human eyes were rooted at one end of each long body, staring up at Washen from what, for lack of a better term, was their heads.

'Welcome,' Washen announced.

Her translator made a low rumbling sound.

'I despise each of you,' she bellowed. Then, following the advice of exopsychologists, she bent over, making eye contact as she reminded these newcomers, 'You have no status here. None. A word from me, and you are crushed in the most horrible ways.'

Human politeness had no place in that alien society.

Flounders - whose real name was a series of poetic ticks — equated kindness with intimacy. And intimacy was afforded only family members, by blood or by ceremony. The exopsychologists were adamant. If Washen couldn't intimidate the Flounders, they would feel uneasy, much i

n the same way that a human woul

d feel uneasy if a stranger approached, referred to her by a lover's nickname, then delivered a sloppy wet kiss.

'This is my ship,' she told her audience.

Several hundred aliens were in shouting range, tiny ears tilted high, absorbing her voice as well as the thunderous rumble of her translator.

'You have paid for my patience as well as a berth,' said Washen. 'Paid with new technologies, which we have already received, mastered, and improved upon.'

Long whiskers stroked each other, the aliens conversing by feel.

Again, she stared into a pair of eyes. Cobalt-blue, utterly alive. 'My rules are simple,

little

monster.'

Whiskers suddenly grew still.

Her audience held its collective breath.

'My ship is

the ship'

she explained. 'It needs no other name. It is remarkable and enormous, but it is not infinite. Nor empty. Thousands of species share its labyrinths with you. And if you do not treat your fellow passengers with complete respect, you will be discarded. Evicted. Rung overboard, and forgotten.'

The breathing resumed, quicker than ever.

Was she playing this game too well?

But instead of holding back, Washen kept pressing. 'An empty chamber has been prepared for you. As you begged us to do. Sealed, and pressurized. With plenty of space, and your ugly foods in abundance. In this new home, you may do as you wish. Unless you wish to procreate, which requires permission from

me.

And fresh payments. Since children are passengers, their status is negotiable. And if I have reason, I will personally throw them overboard. Is that understood?'

Her translator asked the question, then with a soft, sexless voice, offered a sampling of the aliens' replies.

'Yes, Lord Captain.'

'Of course, Lord.'

'You scare me, Lord!'

'When does this show end, Mother? I am hungry!'

Washen strangled a laugh. Then after her own quick breaths, she admitted,'It has been forever since I last threw anyone off

the ship!

Other captains did the banishing. In humane ways, naturally. Taxis or other starships would take the troublesome species home again, or more likely, to obscure worlds where they had a better than fair chance of survival.