Man and Superman and Three Other Plays (60 page)

Read Man and Superman and Three Other Plays Online

Authors: George Bernard Shaw

STRAKER A six shillin novel sort o woman, all but the cookin. Er name was Lady Gladys Plantagenet, wasn't it?

MENDOZA No, sir: she was not an earl's daughter. Photography, reproduced by the half-tone process, has made me familiar with the appearance of the daughters of the English peerage; and I can honestly say that I would have sold the lot, faces, dowries, clothes, titles, and all, for a smile from this woman. Yet she was a woman of the people, a worker: otherwiseâlet me reciprocate your bluntnessâI should have scorned her.

TANNER Very properly. And did she respond to your love?

MENDOZA Should I be here if she did? She objected to marry a Jew.

TANNER On religious grounds?

MENDOZA No: she was a freethinker.

du

She said that every Jew considers in his heart that English people are dirty in their habits.

du

She said that every Jew considers in his heart that English people are dirty in their habits.

TANNER [surprised] Dirty!

MENDOZA It shewed her extraordinary knowledge of the world; for it is undoubtedly true. Our elaborate sanitary code makes us unduly contemptuous of the Gentile.

TANNER Did you ever hear that, Henry?

STRAKER I've heard my sister say so. She was cook in a Jewish family once.

MENDOZA I could not deny it; neither could I eradicate the impression it made on her mind. I could have got round any other objection; but no woman can stand a suspicion of indelicacy as to her person. My entreaties were in vain: she always retorted that she wasn't good enough for me, and recommended me to marry an accursed barmaid named Rebecca Lazarus, whom I loathed. I talked of suicide: she offered me a packet of beetle poison to do it with. I hinted at murder: she went into hysterics; and as I am a living man I went to America so that she might sleep without dreaming that I was stealing upstairs to cut her throat. In America I went out west and fell in with a man who was wanted by the police for holding up trains. It was he who had the idea of holding up motor cars in the South of Europe: a welcome idea to a desperate and disappointed man. He gave me some valuable introductions to capitalists of the right sort. I formed a syndicate; and the present enterprise is the result. I became leader, as the Jew always becomes leader, by his brains and imagination. But with all my pride of race I would give everything I possess to be an Englishman. I am like a boy: I cut her name on the trees and her initials on the sod. When I am alone I lie down and tear my wretched hair and cry Louisaâ

STRAKER [

startled

] Louisa!

startled

] Louisa!

MENDOZA It is her nameâLouisaâLouisa Strakerâ

TANNER Straker!

STRAKER [

scrambling up on his knees most indignantly

] Look here: Louisa Straker is my sister, see? Wot do you mean by gassin about her like this? Wotshe got to do with you?

scrambling up on his knees most indignantly

] Look here: Louisa Straker is my sister, see? Wot do you mean by gassin about her like this? Wotshe got to do with you?

MENDOZA A dramatic coincidence! You are Enry, her favorite brother!

STRAKER 0o are you callin Enry? What call have you to take a liberty with my name or with hers? For two pins I'd punch your fat ed, so I would.

MENDOZA [with grandiose calm] If I let you do it, will you promise to brag of it afterwards to her? She will be reminded of her Mendoza: that is all I desire.

TANNER This is genuine devotion, Henry. You should respect it.

MENDOZA [

springing to his feet

] Funk! Young man: I come of a famous family of fighters; and as your sister well knows, you would have as much chance against me as a perambulator against your motor car.

springing to his feet

] Funk! Young man: I come of a famous family of fighters; and as your sister well knows, you would have as much chance against me as a perambulator against your motor car.

STRAKER [

secretly daunted, but rising from his knees with an air of reckless pugnacity]

I ain't afraid of you. With your Louisa! Louisa! Miss Straker is good enough for you, I should think.

secretly daunted, but rising from his knees with an air of reckless pugnacity]

I ain't afraid of you. With your Louisa! Louisa! Miss Straker is good enough for you, I should think.

MENDOZA I wish you could persuade her to think so.

STRAKER [

exasperated

] Hereâ

exasperated

] Hereâ

TANNER [

rising quickly and interposing

] Oh come, Henry: even if you could fight the President you can't fight the whole League of the Sierra. Sit down again and be friendly. A cat may look at a king; and even a President of brigands may look at your sister. All this family pride is really very old fashioned.

rising quickly and interposing

] Oh come, Henry: even if you could fight the President you can't fight the whole League of the Sierra. Sit down again and be friendly. A cat may look at a king; and even a President of brigands may look at your sister. All this family pride is really very old fashioned.

STRAKER [

subdued, but grumbling

] Let him look at her. But wot does he mean by makin out that she ever looked at im? [

Reluctantly resuming his couch on the turf

] Ear him talk, one ud think she was keepin company with him. [

He turns his back on them and composes himself to sleep

]

.

subdued, but grumbling

] Let him look at her. But wot does he mean by makin out that she ever looked at im? [

Reluctantly resuming his couch on the turf

] Ear him talk, one ud think she was keepin company with him. [

He turns his back on them and composes himself to sleep

]

.

MENDOZA [

to TANNER, becoming more confidential as he finds himself virtually alone with a sympathetic listener in the still starlight of the mountains; for all the rest are asleep by this time

] It was just so with her, sir. Her intellect reached forward into the twentieth century: her social prejudices and family affections reached back into the dark ages. Ah, sir, how the words of Shakespear seem to fit every crisis in our emotions!

to TANNER, becoming more confidential as he finds himself virtually alone with a sympathetic listener in the still starlight of the mountains; for all the rest are asleep by this time

] It was just so with her, sir. Her intellect reached forward into the twentieth century: her social prejudices and family affections reached back into the dark ages. Ah, sir, how the words of Shakespear seem to fit every crisis in our emotions!

And so on. I forget the rest. Call it madness if you willâinfatuation. I am an able man, a strong man: in ten years I should have owned a first-class hotel. I met her; andâyou see!âI am a brigand, an outcast. Even Shakespear cannot do justice to what I feel for Louisa. Let me read you some lines that I have written about her myself. However slight their literary merit may be, they express what I feel better than any casual words can.

[He produces a packet of hotel bills scrawled with manuscript, and kneels at the fire to decipher them, poking it with a stick to make it glow].

[He produces a packet of hotel bills scrawled with manuscript, and kneels at the fire to decipher them, poking it with a stick to make it glow].

TANNER [

slapping him rudely on the shoulder]

Put them in the fire, President.

slapping him rudely on the shoulder]

Put them in the fire, President.

MENDOZA

[startled]

Eh?

[startled]

Eh?

TANNER You are sacrificing your career to a monomania. MENDOZA I know it.

TANNER No you don't. No man would commit such a crime against himself if he really knew what he was doing. How can you look round at these august hills, look up at this divine sky, taste this finely tempered air, and then talk like a literary hack on a second floor in Bloomsbury?

MENDOZA [

shaking his head

] The Sierra is no better than Bloomsbury when once the novelty has worn off. Besides, these mountains make you dream of womenâof women with magnificent hair.

shaking his head

] The Sierra is no better than Bloomsbury when once the novelty has worn off. Besides, these mountains make you dream of womenâof women with magnificent hair.

TANNER Of Louisa, in short. They will not make me dream of women, my friend: I am heartwhole.

MENDOZA Do not boast until morning, sir. This is a strange country for dreams.

TANNER Well, we shall see. Goodnight. [

He lies down and composes himself to sleep].

He lies down and composes himself to sleep].

MENDOZA, with a sigh,follows his example; and for a few moments there is peace in the Sierra. Then MENDOZA sits up suddenly and says pleadingly to TANNER

â

â

MENDOZA Just allow me to read a few lines before you go to sleep. I should really like your opinion of them.

TANNER [

drowsily

] Go on. I am listening.

drowsily

] Go on. I am listening.

MENDOZA I saw thee first in Whitsun week

dx

dx

Â

Louisa, Louisaâ

Â

TANNER [

rousing himself

] My dear President, Louisa is a very pretty name; but it really doesn't rhyme well to Whitsun week.

rousing himself

] My dear President, Louisa is a very pretty name; but it really doesn't rhyme well to Whitsun week.

MENDOZA Of course not. Louisa is not the rhyme, but the refrain.

TANNER [

subsiding

] Ah, the refrain. I beg your pardon. Go on.

subsiding

] Ah, the refrain. I beg your pardon. Go on.

MENDOZA Perhaps you do not care for that one: I think you will like this better. [

He recites, in rich soft tones, and in slow time]

He recites, in rich soft tones, and in slow time]

Louisa, I love thee.

I love thee, Louisa.

Louisa, Louisa, Louisa, I love thee.

One name and one phrase make my music, Louisa.

Louisa, Louisa, Louisa, I love thee.

I love thee, Louisa.

Louisa, Louisa, Louisa, I love thee.

One name and one phrase make my music, Louisa.

Louisa, Louisa, Louisa, I love thee.

Â

Mendoza thy lover,

Thy lover, Mendoza,

Mendoza adoringly lives for Louisa.

There's nothing but that in the world for Mendoza.

Louisa, Louisa, Mendoza adores thee.

Thy lover, Mendoza,

Mendoza adoringly lives for Louisa.

There's nothing but that in the world for Mendoza.

Louisa, Louisa, Mendoza adores thee.

[Affected] There is no merit in producing beautiful lines upon such a name. Louisa is an exquisite name, is it not?

TANNER [

all but asleep, responds with a faint groan

]

.

all but asleep, responds with a faint groan

]

.

MENDOZA O wert thou, Louisa,

The wife of Mendoza,

Mendoza's Louisa, Louisa Mendoza,

How blest were the life of Louisa's Mendoza!

How painless his longing of love for Louisa!

Mendoza's Louisa, Louisa Mendoza,

How blest were the life of Louisa's Mendoza!

How painless his longing of love for Louisa!

That is real poetryâfrom the heartâfrom the heart of hearts. Don't you think it will move her? No answer.

[

Resignedly

] Asleep, as usual. Doggrel to all the world: heavenly music to me! Idiot that I am to wear my heart on my sleeve! [

He composes himself to sleep, murmuring

] Louisa, I love thee; I love thee, Louisa; Louisa, Louisa, Louisa, Iâ

Resignedly

] Asleep, as usual. Doggrel to all the world: heavenly music to me! Idiot that I am to wear my heart on my sleeve! [

He composes himself to sleep, murmuring

] Louisa, I love thee; I love thee, Louisa; Louisa, Louisa, Louisa, Iâ

STRAKER snores; rolls over on his side; and relapses into sleep. Stillness settles on the Sierra; and the darkness deepens. The fire has again buried itself in white ash and ceased to glow. The peaks shew unfathomably dark against the starry firmament; but now the stars dim and vanish; and the sky seems to steal away out of the universe. Instead of the Sierra there is nothing; omnipresent nothing. No sky, no peaks, no light, no sound, no time nor space, utter void. Then somewhere the beginning of a pallor, and with it a faint throbbing buzz as of a ghostly violoncello palpitating on the same note endlessly. A couple of ghostly violins presently take advantage of this bass

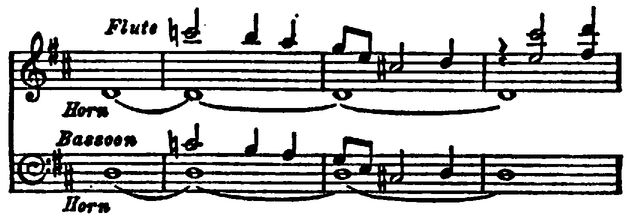

and therewith the pallor reveals a man in the void, an incorporeal but visible man, seated, absurdly enough, on nothing. For a moment he raises his head as the music passes him by. Then, with a heavy sigh, he droops in utter dejection; and the violins, discouraged, retrace their melody in despair and at last give it up, extinguished by wailings from uncanny wind instruments, thus:

â

and therewith the pallor reveals a man in the void, an incorporeal but visible man, seated, absurdly enough, on nothing. For a moment he raises his head as the music passes him by. Then, with a heavy sigh, he droops in utter dejection; and the violins, discouraged, retrace their melody in despair and at last give it up, extinguished by wailings from uncanny wind instruments, thus:

â

It is all very odd. One recognizes the Mozartian strain; and on this hint, and by the aid of certain sparkles of violet light in the pallor, the man's costume explains itself as that of a Spanish nobleman of the XV-XVI century. DON JUAN, of course; but where? why? how? Besides, in the brief lifting of his face, now hidden by his hat brim, there was a curious suggestion of TANNER. A more critical, fastidious, handsome face, paler and colder, without TANNER's impetuous credulity and enthusiasm, and without a touch of his modern plutocratic vulgarity, but still a resemblance, even an identity. The name too: DON JUAN TENORIO, JOHN TANNER. Where on earth

â

or elsewhere

â

have we got to from the XX century and the Sierra?

â

or elsewhere

â

have we got to from the XX century and the Sierra?

Another

pallor

in the void, this time not violet, but a disagreeable smoky yellow. With it, the whisper of a ghostly clarionet turning this tune into infinite sadness:

pallor

in the void, this time not violet, but a disagreeable smoky yellow. With it, the whisper of a ghostly clarionet turning this tune into infinite sadness:

The yellowish pallor moves: there is an old crone wandering in the void, bent and toothless; draped, as well as one can guess, in the coarse brown frock of some religious order. She wanders and wanders in her slow hopeless way, much as a wasp flies in its rapid busy way, until she blunders against the thing she seeks: companionship. With a sob of relief the poor old creature clutches at the presence of the man and addresses him in her dry unlovely voice, which can still express pride and resolution as well as suffering.

Other books

Bachelor Auction by Darah Lace

Not Quite Dead (A NightHunter Novel) by Stephanie Rowe

Empire by Steven Saylor

Possessed by Donald Spoto

Siege Of the Heart by Elise Cyr

Playing With Matches by Suri Rosen

The Inheritance (Volume Three) by Reed, Zelda

Don’t Bite the Messenger by Regan Summers

299 Days: The Collapse by Tate, Glen

Ghettoside by Jill Leovy