Manly Wade Wellman - John the Balladeer SSC (23 page)

Read Manly Wade Wellman - John the Balladeer SSC Online

Authors: John the Balladeer (v1.1)

"But what's

the meaning?" I wanted to know again.

She

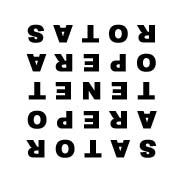

began to write on a paper. "SATOR," she said out loud, "

the

creator

. Whether that's the creator of some machine, or the Creator of all things

. . . I suppose it's a machine-creator."

"I reckon

the same," I agreed her, "because this doesn't sound to me the kind

of way the Creator of all things does His works."

Mrs. Deal smiled

and excused herself. We could talk and talk, she said, but she had sewing to

do.

"AREPO,"

Professor Deal kind of hummed to himself. "I wish I had a Latin

dictionary, though even then I might not find it. Maybe that's a corruption of

repo

or

erepo

—to

crawl or climb—a vulgar form of the word—"

I said nothing. I

didn't think Professor Deal would say anything vulgar in front of a lady. But

all Dr. McCoy remarked him was: "AREPO—wouldn't that be a noun ablative?

By means of?"

"Write it

down like that," nodded Professor Deal. "By means of creeping,

climbing, by means of great effort. And TENET is the verb to hold. He holds,

the creator holds."

"OPERA

is

works

, and ROTAS is

wheels

," Dr. McCoy tried

to finish up, but this time Professor Deal shook his head.

"ROTAS

probably is accusative plural, in apposition." He cleared his throat, long

and loud. "Maybe I never will be sure, but let's read it something like

this:

The creator, by means of

great effort, holds the wheels for his works

."

I'd

not said a word in all this scholar-talk, till then. TENET Might still be

faith

," I offered them.

"Faith's needed to help the workings. Folks without faith might call the

thing foolishness."

"That's

sound psychology," said Professor Deal.

"And

it fits in with the making of spells," Dr. McCoy added on. "Double

meanings, you know. Maybe there are double meanings all along, or triple or

fourfold meanings, and all of them true." She read from her paper.

"The creator, by means of

great effort, holds the wheels for his works."

"It might

even refer to the orbits of planets," said Professor Deal.

"Where do I

come in?" I asked. "Why was I bid here?"

"You can

sing something for us," Dr. McCoy replied me, "and you can have

faith."

A knocking at the

door, and Professor Deal went to let the visitor in. Moon-Eye Newlands walked

into the house, lifted his lantern chimney and blew out his light, He looked

tall, the way he'd looked when first I met him in the outside dark, and he wore

a hickory shirt and blue duckins pants. He smiled, friendly, and moon-eyed or

not, he looked first of all at Dr. McCoy, clear and honest and glad to see her.

"You said

you wanted me to help you, Doctor," he greeted her.

"Thank you,

Mr. Newlands," she said, gentler and warmer than I'd heard her so far.

"You can

call me Moon-Eye, like the rest," he told her.

He was a college

scholar, and she was a doctor lady, but they were near about the same age. He'd

been off to the Korean War, I remembered.

"Shall we go

out on the porch?" she asked us. "Professor Deal said I could draw my

diagram there. Bring your guitar, John."

We went out.

Moon-Eye lighted his lantern again, and Dr. McCoy knelt down to draw with a

piece of chalk.

First she made

the word square, in big letters:

Around these she

made a triangle, a good four feet from base to point. And another triangle

across it, pointing the other way, so that the two made what learned folks call

the Star of David. Around that, a big circle, with writing along the edge of

it, and another big circle around that, to close in the writing. I put my back

to a porch post. From where I sat I could read the word square all right, but

of the writing around the circle I couldn't spell ary letter.

"Folks,"

said Moon-Eye, "I still can't say I like this."

Kneeling where

she drew, Dr. McCoy looked up at him with her blue eyes. "You said you'd

help if you could."

"But what if

it's not right? My old folks, my grandsires—I don't know if they ought to be

called up."

"Moon-Eye,"

said Professor Deal, "I'm just watching, observing. I hdven't yet been

convinced of anything due to happen here tonight. But if it should happen—I

know your ancestors must have been good country people, nobody to be ashamed

of, dead or alive."

"I'm not

ashamed of them," Moon-Eye told us all, with a sort of sudden clip in his

voice. "I just don't think they were the sort to be stirred up without a

good reason."

"Moon-Eye,"

said Dr. McCoy, talking the way any man who's a man would want a woman to talk

to him, "science is the best of reasons in itself."

He didn't speak,

didn't deny her, didn't nod his head or either shake it. He just looked at her

blue eyes with his dark ones. She got up from where she'd knelt.

"John,"

she spoke to where I was sitting, "that song we mentioned. About the

lonesome river ford. It may put things in the right tune and tempo."

Moon-Eye sat on

the edge of the porch, his lantern beside him. The light made our shadows big

and jumpy. I began to pick the tune the best I could recollect it, and sang:

Old Devlins was

a-waiting

By the lonesome river ford,

When he spied the Mackey captain

With a pistol and a sword. . . .

I stopped, for

Moon-Eye had tensed himself tight, "I'm not sure of how it goes from

there," I said.

"I'm sure of

where it goes," said someone in the dark, and up to the porch ambled Rixon

Pengraft.

He was smoking

that cigar, or maybe a fresh one, grinning around it. He wore a brown corduroy

shirt with officers' straps to the shoulders, and brown corduroy pants tucked

into shiny half-boots worth maybe twenty-five dollars, the pair of them. His

hair was brown, too, and curly, and his eyes were sneaking all over Dr. Anda

Lee McCoy.

"Nobody here

knows what that song means," said Moon-Eye.

Rixon Pengraft

sat down beside Dr. McCoy, on the step below Moon-Eye, and the way he did it, I

harked back in my mind to something Moon-Eye had said: about something Rixon

Pengraft wanted, and why he hated Moon-Eye over it.

"I've

wondered wasn't the song about the Confederate War," said Rixon. "Maybe

Mackey

captain

means Yankee captain."

"No, it

doesn't," said Moon-Eye, and his teeth sounded on each other.

"I can sing

it, anyway," said Rixon, twiddling his cigar in his teeth and winking at

Dr. McCoy. "Go on picking."

"Go

on," Dr. McCoy repeated, and Moon-Eye said nothing. I touched the silver

strings, and Rixon Pengraft sang:

Old Devlins, Old

Devlins,

I know you mighty well,

You're six foot three of Satan,

Two hundred pounds of hell. . . .

And he stopped.

"Devils—Satan," he said. "Might be it's a song about the Devil.

Think we ought to go on singing about him, with no proper respect?"

He went on:

Old Devlins was

ready,

He feared not beast or man,

He shot the sword and pistol

From the Mackey captain's, hand. . . .

Moon-Eye looked once

at the diagram, chalked out on the floor of the porch. He didn't seem to hear

Rixon Pengraft's mocking voice with the next verse:

Old Devlins, Old

Devlins,

Oh, won't you spare my life?

I've got three little children

And a kind and loving wife.

God bless them little children,

And I'm sorry for your wife,

But turn your back and close your eyes,

I'm going to take

your—

"Leave off

that singing!" yelled Moon-Eye Newlands, and he was on his feet in the

yard so quick we hadn't seen him move. He took a long step toward where Rixon

Pengraft sat beside Dr. McCoy, and Rixon got up quick, too, and dropped his

cigar and moved away.

"You know

the song," blared out Moon-Eye. "Maybe you know what man you're

singing about!"

"Maybe I do

know," said Rixon. "You want to bring him here to look at you?"

We were all up on

our feet, We watched Moon-Eye standing over Rixon, and Moon-Eye just then

looked about two feet taller than he had before. Maybe even more than that, to

Rixon.

"If that's

how you're going to be—" began Rixon.

"That's how

I'm going to be," Moon-Eye told him, his voice right quiet again.

"I'm honest to tell you, that's how I'm going to be."

"Then I

won't stay here," said Rixon. "I'll leave, because you're making so

much noise in front of a lady. But, Moon-Eye, I'm not scared of you. Nor yet

the ghost of any ancestor you ever had, Devlins or anybody else."

Rixon smiled at

Dr. McCoy and walked away. We heard him start to whistle in the dark. He meant

it for banter, but I couldn't help but think about the boy whistling his way

through the graveyard.

Then I happened

to look back at the diagram on the porch. And it didn't seem right for a

moment, it looked like something else. The two circles, with the string of

writing between them, the six-point star, and in the very middle of everything

the word square:

"Shoo,"

I said. "Look, folks, that word square's turned around."

"Naturally,"

said Professor Deal, plain glad to talk and think about something besides how

Moon-Eye and Rixon had acted. "The first two words are reversals of

the—"

"I don't

mean that, Professor." I pointed. "Look. I take my Bible oath that

Dr. McCoy wrote it out so that it read rightly from where I am now. But it's

gone upside down."

"That's the

truth," Moon-Eye agreed me.

"Yes,"

said Dr. McCoy. "Yes. You know what that means?"

"The

square's turned around?" asked Professor Deal. "The whole thing's

turned around. The whole diagram. Spun a whole hundred and eighty degrees—maybe

several times—and stopped again. Why?" She put her hand on Moon-Eye's

elbow, and the hand trembled. "The thing was beginning to work, to

revolve, the machine was going to operate—"

"You're

right." Moon-Eye, put his big hand over her little one, "Just when

the singing stopped."

He moved away

from her and picked up his lantern. He started away.

"Come back,

Moon-Eye!" she called after him. "It can't work without you!"

"I've got

something to see Rixon Pengraft about," he said.

"You can't

hit him, you're bigger than he is!" I thought she was going to run and

catch up with him.

"Stay

here," I told her. "I'll go talk to him."

I walked quick to

catch up with Moon-Eye. "Big things were near about to happen just

now," I said.

"I realize

that, Mr. John. But it won't go on, because I won't be there to help it."

He lifted his lantern and stared at me. "I said my old folks weren't the

sort you ruffle up for no reason."

"Was the

song about your folks?"

"Sort

of."

"You mean,

Old Devlins?"

"That's not

just exactly his name, but he was my great-grandsire on my mother's side. Rixon

Pengraft caught onto that, and after what he said—"