Margaret Truman (14 page)

Authors: The President's House: 1800 to the Present : The Secrets,History of the World's Most Famous Home

Tags: #Middle Atlantic (DC; DE; MD; NJ; NY; PA), #State & Local, #Buildings, #Public; Commercial & Industrial, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #History, #Presidents - United States, #Washington (D.C.), #United States, #Presidents - United States - History, #General, #Washington (D.C.) - Buildings; Structures; Etc, #Architecture, #Biography & Autobiography, #Fiction, #Juvenile Literature, #Biography, #White House (Washington; D.C.) - History

XI

FDR's death after only eighty-two days of his fourth term catapulted Harry S Truman into the White House. Although he was often taken to task in the press, historians seem to agree his performance was pretty creditable. But he, too, had more than his share of troubles with reporters, beginning with the very fundamental question of where they were going to meet.

The West Wing was already bursting at the seams, and one of Dad's first orders of business was to find a way to enlarge it. Plans were drawn up for an expansion that would provide more office space, a staff cafeteria, a new pressroom, and an auditorium where press conferences could be held. In December 1945, Congress approved an appropriation that would cover the cost of the added space.

But when a sketch of the proposed addition to the West Wing appeared in the newspapers, the public was convinced that the White House itself was going to be changed and no amount of explanation could persuade them otherwise. Always sensitive to the voice of the voters, Congress amended the appropriation bill and the precise amount allotted for enlarging the West Wing disappeared.

Ironically, it was the president perhaps with the strongest antipathy to the media who finally managed to get them decent facilities. Annoyed at the noisy, messy pressroom adjoining the lobby where his visitors entered, Richard Nixon started looking for new space. He found it in the basement of the West Wing, where Franklin D. Roosevelt had installed the swimming pool he used as therapy for his polio-damaged legs. The swimming pool was torn out and the space was reconfigured to accommodate a press center with a briefing room where the White House press secretary could fill reporters in on the latest news from the Oval Office.

Plans are in the works for a new pressroom to be built under the West Wing drive. Whenâand ifâit is completed, the new facility will spell the end of Pebble Beach, but it seems unlikely that its disappearance will provoke an uproar. No one will miss the crush of lights and cameras on the White House lawn, least of all the TV reporters who have to endure all kinds of bad weather in the course of doing their jobs.

XII

Like presidents before him and since, Dad acquired a low opinion of newspapermen during his White House years. Always mindful of history, he dug into the press relations of previous presidents and was comforted to discover he was not alone.

“It seems that every man in the White House was tortured and bedeviled by the so-called free press,” he wrote to his sister. “They were lied about, misrepresented and actually libeled, and they have to take it.”

With this as background, you can easily imagine why I administered one of the worst shocks of Dad's postpresidential life when I called him from New York to tell him I had fallen in love and was planning to marry a man named Clifton Daniel.

“What does he do for a living?” Dad asked.

“He's a newspaperman.”

There was a moment of thunderstruck silence on the Missouri end of the phone. Finally, gamely, Dad said: “Well, if you love him, that's good enough for me.”

(P.S. They got along beautifully.)

XIII

In 1954, Dwight Eisenhower became the first president to hold televised news conferences. Ike was coached in advance by actor Robert Montgomery and the telecasts were carefully stage-managed by Ike's press secretary, who reserved the right to edit the tapes before they were released to the public.

Both televised press conferences and stage-managing were raised to high arts by Ike's successor, John F. Kennedy. JFK's first press conference was broadcast live from the East Room, beginning what one weekly newsmagazine called “a new era in political communication.”

The president, who was not only young and handsome but had a quick wit and an engaging manner, apparently had no difficulty pulling whatever facts he needed from his agile brain on demand. Not many people knew that his astute press secretary gave him a thorough briefing on the probable questions just as Ike's had done.

When it came to charming the press, Jack was well on his way to outclassing Franklin D. Roosevelt. He had also mastered the Rooseveltian art of manipulation. He leaked stories, planted news, gave exclusives to favored journalists, and played reporters off against each other. Like FDR, he was not above withholding news from the media when it suited his interests. As he remarked to one of his staff members, “Always remember that their interests and ours ultimately conflict.”

XIV

The undeclared war between the press and the president saw the media's greatest triumph when a pair of investigative reporters from

The Washington Post

found an anonymous source who filled them in on the doings in the Nixon White House during the Watergate affair. Their stories made front page news and helped to drive Nixon out of office. But while the press was busy congratulating itself on the victory, the White House was gearing up to fight back.

Under Gerald Ford, Richard Nixon's successor, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue started to become a media powerhouse in its own right. The press office staff was increased to forty-five people, about seven times more than there were in John F. Kennedy's day.

The trend continued under President Jimmy Carter. In 1978, the Carter press office, now called the Office of Media Liaison, regularly sent out thousands of press releases, audio-tapes, and films to news organizations each month. The output grew even larger under Presidents Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and Clinton. In this blizzard of information and images, press conferences lost much of their importance. In Ronald Reagan's administration, reporters were often reduced to screaming questions at the president as he boarded his helicopter on the White House lawn.

During the Clinton tenure, press conferences were reduced to the vanishing point. The Clinton White House preferred to rely on its own awesome ability to communicate directly to the American people. The Clinton White House beamed programs to public and commercial television stations at the rate of one a day. Meanwhile the White House Web site (

www.whitehouse.gov

) was bundling transcripts of the president's speeches over the Internet and streaming live interviews with the president, in which fifteen thousand people could fire E-mail questions at the Oval Office. This led one reporter to suggest that the “White House propaganda machine has . . . clearly been winning the battle” for control of public opinion.

I have too much faith in the people who write and edit and broadcast the news to believe that this can ever be the case. When President George W. Bush took office, his press secretary warned the media not to expect him to hold formal press conferences in the East Room, like many of his predecessors. Instead, he would hold them in the White House briefing room, supplement them with informal chats with reporters, and answer a few questions during photo ops.

I was concerned at first. Then I read an interview with my old friend Helen Thomas, who has been covering the White House since John F. Kennedy took office in 1961. Helen has made more than one president squirm at a press conference.

Was she concerned about Bush's approach? “I don't think it matters when or where the press conference is held,” she said, “just so we really get a crack at him.”

She went on to point out that press conferences are the only real chance Americans have to question their president. With Helen and her colleagues around, we are unlikely to lose that chance. That means sooner or later at least some of the truth about what's happening in the White House is going to reach the American people, whether the president likes it or not.

Questions for

Discussion

Why are presidents wary of the media?

How can a good press secretary improve a president's relations with the press?

Why should presidents meet with reporters on a regular basis?

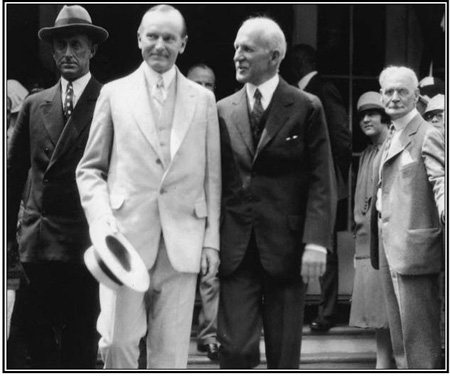

The man on the left of President Calvin Coolidge is Secret Service agent EdmundStarling. Of the five presidents he protected, Coolidge was his favorite.

Credit: U.S. Secret Service

14

Keeping Killers and Kooks at Bay

MY PARENTS HAD to move to Blair House while the White House was undergoing its historic foundation-to-roof reconstruction, but the West Wing was perfectly sound so there was no reason why my father couldn't continue to work in the Oval Office. The only question was: How would he get there?

The West Wing is only a few steps across Pennsylvania Avenue, but Jim Rowley, the Secret Service agent in charge of the White House detail, wanted him to go by car. Dad was not too happy about the idea. “Can you imagine being driven across the street?” he said. But he took Jim's advice.

A couple of years later, Dad had reason to be glad the Secret Service was on the job. On November 1, 1950, around two P.M., two armed Puerto Rican nationalists, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, approached Blair House. My father and mother were upstairs dressing to go to a ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery. I was far away, preparing to give a concert in Portland, Oregon.

The two gunmen planned to assassinate the president on behalf of Puerto Rican independence. Collazo, who had never fired a pistol before in his life, approached from the east, Torresola from the west. They planned to meet on the front steps of Blair House and charge inside together.

The house was guarded by White House policemen in booths at either end of the building. Another policeman, Donald T. Birdzell, was on duty at the front door, which was open to the mild fall weather. Only a lightly latched screen door prevented access from the street.

Collazo mingled with some tourists as he passed the east booth. When he was within three or four feet of the front door, he whipped out his pistol, aimed it at Birdzell, and pulled the trigger. Nothing happened.

If that pistol had gone off, the plot might well have succeeded. With Birdzell dead, Collazo planned to whirl and shoot the guards in the east booth while his partner took care of the men in the west booth. After that the only person between them and the president would have been the Secret Service man stationed at the head of the stairs to the second floor. The assassins might have shot him, too, leaving the president and first lady unprotected.

Hearing the click of Collazo's gun, Birdzell turned to find him pounding on the jammed pistol. It suddenly went off, striking the policeman in the knee. Not wanting to fire with pedestrians in the area, Birdzell stumbled down the steps to the street before drawing his gun. A Secret Service agent who was with the policeman in the east booth opened fire. Meanwhile, Torresola reached the west booth and quickly pumped two bullets into policeman Leslie Coffelt and another slug into Joseph Downs, the other policeman in the booth. Whirling, he took a second shot at Birdzell and another policeman coming out a basement door. As Torresola paused to reload his gun, the dying Coffelt tottered to the doorway of the west booth and put a bullet in his brain. By this time, three shots fired by other policemen and Secret Service agents had hit Collazo. In less than two minutes twenty-seven shots had been fired.

My parents left for the dedication ceremony on schedule. “A president has to expect these things,” Dad said. The next day, at a press conference, he told the reporters, “I was never in any danger. The thing I hate about it is what happened to these young menâone of them killed [Coffelt] and two of them [Downs and Birdzell] badly wounded.”

II

There are any number of people who gravitate to Washington from all parts of the country to tell the president their troubles, or to give him advice on his troublesâor to do him serious bodily harm. The Secret Service has been trying to keep them at bay for over one hundred years, with varying degrees of success.

If you have any doubts about the need for the Secret Service, consider these statistics. One in every three presidents has been shot at or otherwise attacked. Four have been killed by assassin's bullets. In the past few decades, Gerald Ford survived two blasts of gunfire and Ronald Reagan came within a hairsbreadth of being killed by a seriously disturbed man who thought shooting a president would impress screen star Jodie Foster.

In the beginning, the president had no protectors. Thomas Jefferson included guardhouses in his plans to complete the White House but no one, including him, implemented the idea. Luckily, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe escaped unscathed and unthreatened, except for Madison's encounter with those red-coated pyromaniacs in 1814.

John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson displayed no interest in employing bodyguards, although Jackson could have used them. On January 30, 1835, he was striding through the rotunda of the Capitol when an assassin stepped out of the crowd and aimed a pistol at his heart from a distance of about three feet. The gun barked but only the cap exploded, not the charge that fired the bullet. Cursing, the would-be killer whipped another pistol from beneath his coat and pulled that trigger. The same thing happened.

The infuriated Jackson bashed his attacker with his cane and seven or eight congressmen piled on top of the man, who shouted that Jackson was preventing him from becoming king of England.

The two guns were taken to an armory where experts tested them. They were in perfect working order and fired bullets the first time someone pulled their triggers. The experts estimated the odds against both guns failing to work were about 1 in 125,000.

If there is any conclusion that can be drawn from this incident, it may be that some presidents lead charmed lives and others are just unlucky.

III

Abraham Lincoln began receiving death threats almost from the day he was elected. He had won with only forty percent of the popular vote, which left a lot of the country angry. By the time the new president set out for Washington, D.C., in February 1861, most of the South had seceded and the atmosphere was even more rancid. Lincoln's former law partner and a professional detective made the journey with him, armed with knives and pistols.

As the war between the North and the South escalated, so did Lincoln's death threats. There were more than enough to make him acutely conscious of his safety. He saw to it that the doormen and many of the inside servants were armed. A contingent of plainclothesmen from the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police was hired with instructions to conceal their guns by wearing suits that were a size too big for them.

In this tense atmosphere, First Lady Mary Lincoln became the victim of an apparent assassination attempt. In July of 1863, she was staying in a house at the Soldiers' Home in northeast Washington, where the Lincolns spent their summers. Confederate and Union armies were locked in a death struggle near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Desperate to hear some news, the first lady climbed into her carriage and ordered the driver to head for the White House at top speed.

As they hurtled down the road, the carriage suddenly disintegrated. Mrs. Lincoln and the coachman were flung headfirst into the dirt. By a miracle, they both escaped serious injury. Many people concluded that the carriage had been tampered with in the hope of killing the president.

Another time, when Lincoln was riding out to spend the night at the Soldiers' Home, a gunshot startled his horse. The president thought it was an accidental discharge, until someone inspected his hat and found a bullet hole. Thereafter, he never rode anywhere without a cavalry escort.

Despite his precautions, Lincoln still fell victim to an assassin's bullet. He died because he and his guards wrongly assumed that with the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, the Civil War was over and there was no longer any need for vigilance. The moral of the tragic story of Lincoln's decision to go to Ford's Theater on Good Friday night is one that the modern Secret Service never forgets. A president is never safe, anytime, anywhere.

IV

En route to that grim conclusion, two other presidents had extremely narrow escapes. Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, stepped out of his office on the second floor one day to find a madman with a loaded gun rampaging down the hall. Johnson shouted for help and several servants and aides leaped on the man, who for some unknown reason did not pull the trigger.

Next on the close call list was Benjamin Harrison. One evening in 1891, shouts and the sounds of a struggle drew him to the Red Room. He found two doorkeepers wrestling with a deranged man wielding a knife. The president helped the doormen pin the intruder down and cut a length of window cord to tie him up.

These incidents were quickly forgotten, but the deaths of two other presidents could not be so easily overlooked. James Garfield was struck down by the bullets of a crazed job seeker as he walked through the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad Station in July of 1881. Next to die was William McKinley, in a scene that no modern Secret Service man can read about without wincing.

The president was in Buffalo, New York, to open an exposition. On September 5, 1901, he arrived at the exposition grounds for a public reception that was supposed to last only ten minutes. Twice McKinley's secretary, George Cortelyou, had scrubbed this event, arguing that it was dangerous. Twice the president had written it back into the schedule, saying: “No one would wish to hurt me.”

Although Cortelyou dropped the subject, he made sure there was plenty of security. Eighteen exposition policemen and eleven well-armed soldiers formed a lane through which people passed to greet the president. Three Secret Service agents were also on hand.

The Secret Service had been organized by the Treasury Department in 1865 to investigate and prevent counterfeiting. It was not responsible for protecting the president but its agents helped with security on an informal basis. Unfortunately, the arrangements were so informal that no one was really in charge. Nor did the agency have any system to detect potential killers before they struck. One of these, a man named Leon Czolgosz (pronounced

chol-gosh

) entered the line of handshakers without the slightest difficulty.

Czolgosz, a native of Cleveland, had suffered a mental breakdown some years earlier. He drifted into anarchism, a philosophy that considered all rulers evil, and became obsessed with the assassination of the king of Italy in 1900 by an American-born anarchist. Czolgosz had been talking about killing McKinley ever since.

Incredibly, not one of the supposedly alert guards noticed when Czolgosz, while standing in the receiving line, drew a pistol from his pocket and wrapped a handkerchief around it, making it look as if he were wearing a bandage on his right hand. By awful coincidence, the man just ahead of him had an authentic bandage on his right hand. When the man reached the president, he said: “Excuse my left hand, Mr. President.” McKinley smiled and shook his left hand.

When Czolgosz approached the president, he, too, extended his left hand. As McKinley reached for it, the anarchist fired two shots through the handkerchief at point-blank range. The president toppled backward into the arms of those around him. Fatally wounded, he died eight days later.

The sad story almost speaks for itself. Today, the Secret Service would very likely have heard of Czolgosz before he even got to Buffalo. Assuming the killer made it that far, they never would have let him get away with his gun-wrapped-in-a-handkerchief ruse. Even the innocent man who preceded him would have been hustled off before he got anywhere near the president.

V

After the McKinley assassination, the Secret Service was put in charge of protecting the president and two agents were assigned full-time to the White House detail. Even then there were lapses.

Theodore Roosevelt often had evening appointments. Most of his callers were known in advance, but occasionally there were people whom the president had asked to stop by without bothering to add their names to his schedule.

One evening a man appeared in full evening dress, complete with top hat, and informed the usher on duty at the front door that he had an appointment with the president. The man was invited to step into the Red Room and another usher went upstairs to tell the president that Mr. John Smith was there to see him. Roosevelt could not recall making an appointment with Mr. Smith but he decided to see him anyway.

The president went downstairs and within minutes pressed the call bell that summoned Chief Usher Ike Hoover to the Red Room. When Hoover entered, Roosevelt walked over to him and said quietly, “Take this crank out of here.”

The president quickly left the room by another door while the chief usher signaled for help. When the visitor was searched, he was found to be carrying a large-caliber pistol.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, the White House became a magnet for people who blamed the president for the collapse of the nation's economy. Herbert Hoover was inundated with death threats, crank letters, and bizarre visitors.

As a result, forty to fifty men were assigned to the White House Police Force and two Secret Service men accompanied the president whenever he went out. When he traveled, the number of agents was increased to eight or ten and additional men were recruited from Secret Service field offices in the areas he was visiting. In addition, White House visitors were subjected to greater scrutiny. Briefcases, cameras, and women's purses had to be inspected before their owners were admitted and anyone carrying a package was forbidden to approach the president.

In spite of this extra effort, slipups still occurred. Franklin D. Roosevelt's oldest son, Jimmy, tells a story that the Secret Service would rather forget. One night during World War II, he was home on leave and joined his parents at the White House for dinner. Afterward they watched a movie. When the lights came on, a neatly dressed young man, a complete stranger, was standing next to FDR.

Instead of brandishing a weapon, however, the interloper asked for the president's autograph. Somehow, apparently for a lark, he had gotten past the doormen and the Secret Service to penetrate the heart of the house. FDR gave him the autograph and the embarrassed Secret Service men escorted him to the door. You can be sure this breach of White House security never happened again.