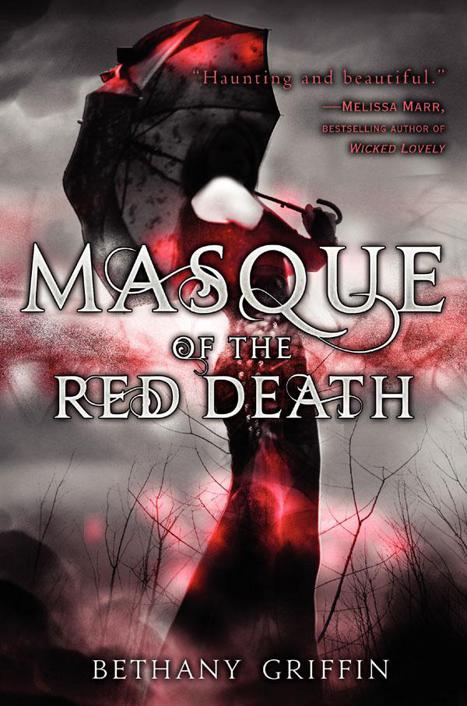

Masque of the Red Death

Read Masque of the Red Death Online

Authors: Bethany Griffin

Tags: #Love & Romance, #Love, #Wealth, #Dystopian, #Adventure and Adventurers, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Plague, #Historical, #General, #Science Fiction, #David_James Mobilism.org

MASQUE

OF THE

RED DEATH

BETHANY GRIFFIN

TO LEE, WHO IS ALMOST ALWAYS RIGHT,

BUT RARELY SMUG ABOUT IT

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

T

HE CHARCOAL SKY SPITS COLD RAIN AS WE

rumble to a stop at a crossroad. A black cart blocks the road, and even in an armored carriage we know better than to force our way past.

Burly men stagger to the cart, carrying something between them. Someone. One of the men stumbles, and the body wobbles in a horrifying way.

My friend April gags behind her mask. “Too bad your father didn’t design these things to keep out noxious smells as well as noxious diseases.”

I wonder whether the people remaining in the houses will be cold tonight. If they’ve wrapped their dead in their only blankets. They should know better.

The corpse collectors wear cloth masks, flimsy and useless to stop the contagion. They roll their cart forward a scant hundred yards and stop again, unconcerned that they’re blocking traffic. They don’t care that we have hell-raising and carousing to do in the Debauchery District.

The Debauchery District. The very name makes me shiver.

As I turn to April, prepared to complain about the delay, a girl is pushed through a doorway and into the street.

She is clutching something, and her emergence at the same time that the corpse collectors are making their daily appearance cannot be an accident. Other people appear in the doorway—the inhabitants of the house, perhaps—and I feel afraid for them because not a single one of them wears even a cloth mask.

A corpse collector approaches the girl. Before, I wanted him to hurry, but now each heavy footstep fills me with dread.

The girl is slight, and her ancient dress has been hemmed and stitched so that her arms and legs are visible, but with the rain and the half light, it’s impossible to tell if she is blemished or clean. The people in the house want her to give the man the bundle, but she turns away. It doesn’t take much imagination to realize that she is cradling a baby.

She raises her face to the rain, her misery palpable.

I can’t explain how I know which drops of condensation running down her cheeks are rain and which are tears. But I do.

The girl’s eyes catch mine.

I feel something. The first emotion I’ve felt all day, besides vague anticipation for tonight. This isn’t the sort of thing I want to feel. Gnawing and sick, it wells up from my stomach.

She breaks eye contact when a young man comes out of what’s left of the building; the roof has been blasted away, probably during some useless riot, and now the structure is covered with canvas. He grips the girl’s shoulders and forcibly turns her. I wonder if he is the father, wonder if he cared for the child in the bundle, or if he just wants to get the disease away from him, to keep it from forming a rash that scabs over and sinks through his skin. You don’t recover from this contagion. You contract it, and then you die. Quickly, if you are lucky.

I try to guess the age of the mother. From her posture, I’m supposing that she’s just a girl.

Maybe that’s why I feel connected to her, because we’re the same age.

Maybe it’s the eye contact she initiated. Usually they don’t look at us.

The girl’s grief is a mindless, crushing thing, and somehow I feel it, even though I am supposed to be numb. As the men tear the baby away, I feel an aching loss. I want to stretch out my own arms, pleading, but if I do, April might laugh.

My knees begin to shake. What is wrong with me? Soon I will be crying. At least no one is looking closely enough to discern the difference between

my

tears and the rain.

They toss the tiny body into the cart.

I flinch, imagining that it makes a sound, even though I can only hear the rumble of the carriage and April’s exasperated sigh.

“You would think they’d be happy,” she says. “My uncle is paying a fortune to get rid of the bodies. Otherwise the lower city would be unlivable.”

If I pushed April and her sparkling silver eyelids out of the open carriage, the crowd lining this street might kill her. If I ripped the mask from her face, she’d probably be dead in a couple of weeks.

She doesn’t understand. She was raised in the Akkadian Towers and has never been on the streets. Not this one, not the one half a block to the west, where I once lived in complete darkness. She doesn’t know, and never will.

But I cannot be mad at April. I live for her, for the hours when she makes me forget, for the places where she takes me. Perhaps she’s right, and these people should be thankful to have men tear the corpses from their arms.

Out of the corner of my eye, I notice dark shapes creeping from between two buildings. I strain to see, but they never step out of the gloom. All of a sudden I’m afraid. This area can get violent, fast. The corpse collectors stomp toward another door, marked with a roughly painted red scythe, passing through shadows and back into the light. Their disregard accentuates the care the cloaked figures take to cling to the shadows.

April doesn’t notice.

Anything could be hidden under a dark cloak. Our driver curses and turns sharply, and we finally lurch past the body cart. When I look over my shoulder, the cloaked men have melted back into the shadows.

At last we can get on with our night.

We turn a corner, and our destination becomes visible. It’s in a slight depression, as if the entire city block sank a few feet into the ground after the buildings were erected. There’s a hot-air balloon tied to the top of the tallest building in the area. You can’t see the lettering, but everyone knows it marks the location of the district.

It is a floating reminder—not that we used to invent things and travel, but that if you can get to the place where the balloon is tethered and if you have enough money, you can forget about death and disease for a few hours.

“You’re a million miles away,” April says in the small voice she uses when she arrives earlier than expected and finds me gazing out into the falling rain.

I don’t know why she seeks out my company. She is animated. I’m barely alive. I stare into space and whimper in my sleep. When I’m awake, I contemplate death, try to read, but never really finish anything. I only have the attention span for poetry, and April hates poetry.

What April and I share are rituals, hours of putting on makeup, glitter, fake eyelashes glued on one by one. Our lips are painted on with precision; mindless mirror staring isn’t that different from gazing out into the toxic slush, if you really think about it. She could share this with anyone.

There’s no reason that it has to be me.

“Tonight is going to be insane,” she says happily. “You wait and see.”

People whisper about the Debauchery Club in the tattered remains of genteel drawing rooms, while they sip a vile substitute for tea from cracked china cups. Real tea was imported; we haven’t had anything like that in years.

The first club we pass is the Morgue. It’s in an abandoned factory. They made bricks there, back when builders used to construct houses. We won’t need to build anything until all the abandoned buildings collapse, if there are any of us left by then.

The line to get into the Morgue stretches around the block. I scan the crowd, imagining that they are hopeful, that they crave admission as if their lives depended on it, but we’re too far away to read the expressions on their masked faces.

April and I pass this way frequently but never go inside. We are bound for the Debauchery Club, the place this entire district is named for. Membership is exclusive.

Our driver lets us out in an alley. The door is unmarked and unlocked. When we step into the foyer, it is completely dark except for a succession of throbbing red lights that are part of the floor. No matter how many times we come here, they still fill me with curiosity. I run my foot over the first one in the hallway, looking for some texture, something that differentiates it from the rest of the floor.

“Araby, come on.” April rolls her eyes. We remove our masks and place them in velvet bags to keep them safe.

Before the plague, the Debauchery Club was only open to men. But, like everyone else, the majority of the members died.

April and I are probationary members, sponsored by her brother, whom I have never met. We won’t be eligible for full membership until we are eighteen.

“This way, ladies.”

I catch a glimpse of myself in a mirror and smile. I am not the person I was this morning. I am beautiful, fake, shallow, incognito. My black dress reaches my ankles and flows over the whalebone corset that I appropriated from my mother’s closet. It’s not an outfit I could wear on the street, but I love it. I look impossibly thin and a little bit mysterious.

For a moment I am reminded of cloaked figures, also swathed in black, and smooth my dress nervously.

“I’ll loan you a pair of scissors,” April teases as she enters the examination room.

I laugh. Her own skirts are artfully cut above her knees. Our fashions changed when the Weeping Sickness first came to the city. Long skirts could hide oozing sores.

I savor the feel of my skirts around my legs as I turn, watching myself in the mirror.

“Your turn, baby doll.”

I follow the velvety voice into the examination room.