Massacre in West Cork (20 page)

Read Massacre in West Cork Online

Authors: Barry Keane

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #irish ira, #ireland in 1922, #protestant ireland, #what is the history of ireland, #1922 Ireland, #history of Ireland

In his case it must have been out of his sense of loyalty on the one hand and his source of resentment against young men of his own locality whom he regarded as his enemies – it must be one or other of those two things that prompted him to turn informer. I knew that man in my young days and I never heard one word of suspicion uttered against him. He was a loyalist, yes, but many others were loyalists as well as he was and they did not do what he did.

51

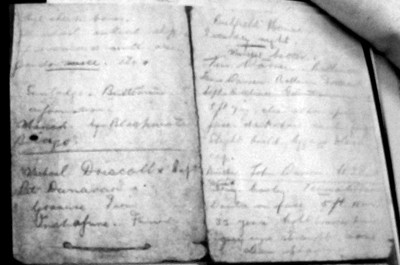

Two pages from the Auxiliary intelligence diary (courtesy of the Bureau of Military History)

The article clearly rules out any of the men shot during the Dunmanway killings being taken from this list, as this loyalist was still alive after 1922 and the other three men are clearly identifiable in the military archives and do not include those killed.

According to Flor Crowley, the diary and the other papers found in the workhouse had been sent to IRA headquarters in Bandon for analysis. As previously stated, Meda Ryan suggests that those shot in Dunmanway were listed as ‘helpful citizens’ in the Dunmanway ‘find’.

52

She claims that all the names of those killed are to be found in documents that were in the possession of Dan Cahalane, or in Tom Barry’s private correspondence, or in other documents and evidence in her possession or that she has seen.

53

Such is the controversy surrounding this subject that all source documents should be made publicly available – redacted if necessary. This includes Peter Hart’s anonymous interviews.

Two other entries in the diary may be related to the men shot in 1922: the first is ‘“Rushfield House” Saturday night’ (underlined). In the 1911 census in Bengour, William Howe owned Rushfield House in Castletown-Kinneigh. He was likely to have been a cousin of Robert Howe, and Rushfield is only two kilometres from Prospect Cottage in Ballaghanure where Robert was shot. This connection between Rushfield House and the Auxiliary diary may have caused Robert Howe to be targeted in error by individuals who knew a Howe in Castletown-Kinneigh was in the diary, or it may just be a coincidence. It is also possible that John Chinnery was shot because he was William Howe’s nephew.

The case of Robert Howe has always been particularly problematic, as there is no evidence to connect him to any anti-Sinn Féin conspiracy. Even Peter Hart’s attempt to explain his targeting is unsatisfactory. Hart states that he was ‘no stranger to political controversy, having been accused of slander during the 1914 county council elections’.

54

In fact, Howe took out an advertisement to apologise to local national schoolteacher Patrick Galvin for claiming that ‘he had sold his vote for a pecuniary consideration’.

55

As there is no mention of any political affiliation, it is hard to see the relevance of this to the later murders.

John Chinnery must be considered in tandem with Robert Howe. The Chinnery household is fifty metres south-east of Prospect Cottage, and the Howes and Chinnerys were most likely distant relations.

56

Given that they lived next door to one another, it is possible that Chinnery and Howe were actually shot for the trivial reason of refusing the ‘order’ to harness a horse by a couple of trigger-happy gunmen heading west to shoot John Buttimer and James Greenfield at Caher, five kilometres (an hour’s walk) to the west. However, Meda Ryan states that a 1949 letter from Risteárd Ó Glaisne, in Tom Barry’s private collection, says that John Chinnery had been targeted by the IRA on a number of occasions after the IRA had caught him red-handed when he dropped a letter he was posting to the British Army.

57

Again the reader will have to weigh this information and decide how valuable Ó Glaisne’s letter is, given the fact that it was written more than twenty years after the event.

The second entry that may be connected with the 1922 killings says ‘Sun Lodge – information Buttimer Manch – by Blackwater Bridge’. Sun Lodge is marked on the 25-inch Ordnance Survey map just off the main Dunmanway–Bandon road at Manch. John Buttimer and James Greenfield lived in Caher, less than two kilometres away up the hill from Sun Lodge, and it is possible that this diary information may have been used to target these victims.

Among modern historians, only Meda Ryan has seen all the available documents that were part of the Dunmanway ‘find’. I do not know if the pages in the Military Archives are the complete ‘find’ but I am certain that they are exactly the same documents covered in the 1971 series by Flor Crowley. As the diary does not identify the 1922 men as spies, and the only loyalist spy it mentions was alive after the killings (according to Flor Crowley in 1971), it is difficult to see – other than for the Rushfield and Sun Lodge entries – what relevance it may have had.

Turning to how the rest of the men were targeted, it must be remembered that Michael O’Neill’s brother, Sonny, was the intelligence officer of the Southern Brigade and would have had access to all information in the brigade’s possession.

58

If he was asked by the killers, it is possible that he might have provided some of the information that caused the targeting of these men. As there is no openly available verifiable documentary evidence to either confirm or deny this theory, it is impossible to make a proper judgement on it, but nothing suggests that he was involved.

In Tom Barry: IRA Freedom Fighter Meda Ryan states that Dunmanway woman Eileen Lynch told her that, as children, they had been warned away from David Gray because his kindness was a mask for gathering information. Ryan says that both David Gray and Francis Fitzmaurice have been ‘firmly established’ as spies, but presents no reference for this.

59

It is difficult to assess the value of the evidence of someone who was a child in 1922, although Lynch undoubtedly gave an accurate portrayal of what she remembered. She also lists five Protestant families in Dunmanway who she said were either helpful to their Catholic neighbours or actively nationalist: O’Meara, Atkins, Smyth, Cox and Wilson. However, some doubt is cast on her recollection when other facts are considered. For example, one of the three Wilson families in the town was caught up in the Dunmanway killings and fled to England for a month. The other was the rector’s family, who remained, and the other Wilsons were Roman Catholic. The only Smiths or Smyths in the town were also Roman Catholic and provided a car for Tom Barry after the Fanlobbus ambush.

60

There is another possible reason for the killings. An amnesty had been granted to all for the ‘wrongs of the past’ once the Treaty was signed in December 1921 and was issued on 9 February 1922 by the Provisional Government, but it only went as far as the writ of the Free State ran.

61

Collins may have unintentionally stoked the pot by replying forcefully to Lord Bandon ‘that loyalists will be afforded the protection of the government in accordance with the recent amnesty proclamation’ in a letter published in the Southern Star on 8 April. The West Cork IRA may well have repudiated any such proclamation, as it did not recognise the Provisional Government, but there is no evidence of this.

It has been suggested that the victims of April 1922 were members of either the Protestant Action Group or the Anti-Sinn Féin Society, which would explain their targeting, but many scholars, including Hart and Murphy, claim that these names were a cover for the Auxiliaries, ‘who dressed up as a bunch of old farmers’ to go on raids, and evidence of an ‘unfailing IRA belief in conspiracy theories’, and they dismiss the possibility of a native Anti-Sinn Féin group existing in Bandon.

62

This might be the case, but Meda Ryan argues, with justification, that there is ample evidence of a local Anti-Sinn Féin Society from both published sources and IRA interviews.

63

Ryan states that the 1922 victims were shot because they were known members of this Anti-Sinn Féin Society. Even Thomas J. Bradfield’s inadvertent confession provides some evidence of this group’s existence. The testimony of Major Neave – the Officer Commanding the Essex Regiment in Bandon – to the Wood-Renton Compensation Committee also supports the existence of such a group. He stated, ‘There had been rumours of an Anti-Sinn Féin Organisation.’

64

As he shamelessly lied in much of the rest of his evidence, it is difficult to assess the honesty of this statement.

However, there can be no such doubt about a confidential report by the Bandon RIC Divisional Commissioner for March 1921 that a shed used by Sinn Féin was burned by ‘members of the Anti-Sinn Féin Society’. This is conclusive proof of its existence, but not of its membership.

65

Nor is there any doubt that the Divisional Commissioner of the RIC in Cork, Major Moore, told British civil servant Mark Sturgis that an Anti-Sinn Féin Society existed in the city. While Major Moore attempted to minimise the role of the British Army in starting the fires in Cork in December 1920, he was unequivocal about the Anti-Sinn Féin Society: ‘The Anti-Sinn Féin League does exist and is not a myth to cover the “Armed Forces of the Crown”.’ As a result, it defies logic to claim that an Anti-Sinn Féin Society of local unionists did not exist.

66

However, this is not evidence that the victims of April 1922 were members.

The BMH files present the strongest claim for the involvement of the victims of the Dunmanway and Ballygroman killings in an anti-Sinn Féin organisation from inside the anti-Treaty IRA. When Michael O’Donoghue was moved to Bandon, he was intimately involved in the 3rd Brigade’s affairs until his transfer to Donegal at the end of March 1922. Along with Michael O’Neill, he certainly saved one love-struck Black and Tan’s life in February 1922. Writing in 1952, long before there was any controversy about the motive for the Dunmanway killings, O’Donoghue’s analysis is blunt, unemotional and unapologetic:

Several prominent loyalists – all active members of the anti-Sinn Féin Society in West Cork, and blacklisted as such in I.R.A. Intelligence Records – in Bandon, Clonakilty, Ballineen and Dunmanway, were seized at night by armed men, taken out and killed. Some were hung, most were shot. All were Protestants. This gave the slaughter a sectarian appearance. Religious animosity had nothing whatever to do with it. These people were done to death as a savage, wholesale, murderous reprisal for the murder of Mick O’Neill.

67

He said that the killings were ‘murderous’ and that some of the men ‘were hung’, which agrees with Alice Hodder, who claimed the Hornibrooks were hanged. Writing at a time when there was no controversy, did he have any reason to lie? To put it bluntly, why admit that the anti-Treaty IRA committed these murders if it did not? Why say the men were members of an Anti-Sinn Féin Society if they were not? This is the simplest explanation for the killings, and in the face of O’Donoghue’s statement there is no need to build complex theories about what might have happened. Crucially, the leadership of the Cork IRA were out of the county on 27 April 1922 at a final meeting in Dublin to try to avert civil war.

68

If they had been in West Cork, they would have exerted some discipline on the men under their command. The fact that they stopped the killings when they returned proves this.

However, caution is necessary, as only one BMH statement or memoir mentions O’Donoghue. This is from Seumas O’Mahony, who was a member of the UCC IRA Company. According to O’Mahony, along with O’Donoghue, the UCC IRA Company included Mick Crowley, a section leader in Tom Barry’s column, and Pete Kearney. These are Mick Crowley of Kilbrittain and Peadar Kearney of Dunmanway, both of whom are central to this story. The press reports noted that O’Donoghue was an ‘engineering officer of the West Cork 3rd Brigade’ after his election as GAA President in 1952. Given Tom Barry’s robust manner and the fact GAA Secretary Pádraig Ó Caoimh had been an officer of the Cork Brigade in the War of Independence, O’Donoghue could not tout his war record during an extremely tight presidential election, which he won by three votes, unless it was true. He also reiterated it in his acceptance speech at the GAA convention.

69