Master Thieves (20 page)

Authors: Stephen Kurkjian

Getting an accurate account of what had happened in the pre-dawn hours of March 18, 1990, what had motivated the largest art theft in world history, and where the stolen pieces had been stashed was the priority of reporters like me. The ultimate, if not only, aim of the FBI's Boston office, however, was to return those paintings to the museum's gallery walls. By using what the FBI had learnedâor perhaps, even more, what it appeared to have learnedâfrom its success in capturing Whitey Bulger, the FBI felt they could find this out by piquing public interest.

As DesLauriers stated in closing his remarks at his March 2013 press conference: “To close the book on this theft we need to recover the art and return it to its rightful owner. We are calling upon the American public to assist us in this investigation, as they have so many times before.”

And then, not long after the Boston Marathon bombing took everyone's attention away from the Gardner press conference, just as it seemed that the secrets of the Gardner case would die in the murky Boston underworld, a call from a rival gang would call into question all of the FBI's assumptions.

A Tale of Two Gangs

T

he Boston mob

in the 1980s was in complete chaos.

After Raymond Patriarca, an Italian mobster who had ruled the New England mob with an iron fist for more than thirty years, died in 1984, leaving control with his son, there was a scramble for primacy among the gangland thugs.

Raymond Junior was neither as smart nor as brutal as his father. After all, who could have been as tough as the man who had ordered a man under his control to kill his own son because a deal-gone-wrong had cost Patriarca money? Struggling to live up to his dad's

Godfather-

like reputation, the younger Patriarca had a tentative grip on things, at best.

A second shock hit the Boston underworld when Gennaro Angiulo, who with his brothers ran the city's criminal organization as Patriarca's underboss, was indicted and jailed.

For several years, with no single individual emerging with the necessary power and prestige to lead the underworld,

several smaller rings that had operated under Patriarca and Angiulo's authority jockeyed for control. One such group, out of Boston's North End, included the mob soldiers Vincent A. Ferrara, Joseph A. “J. R.” Russo, and Angelo “Sonny” Mercurio.

And of course, there was South Boston mobster James “Whitey” Bulger, who had the force and toughness to carve out his own place in Boston's mob scene. Bulger operated independently of the Angiulos, yet had been as murderous as any gang leader in America. Two obstacles stood in Bulger's way, however. He wasn't Italian and, in 1988, it was revealed in a series by the

Boston Globe

that he had enjoyed a “special relationship” with the FBI as a key underworld informant.

On the cusp of that revelation, when all-out war seemed inevitable, one of Bulger's allies, Frank “Cadillac” Salemme, was released from jail. Salemme faced neither of Bulger's obstacles in seeking leadership of the Boston mob, and he immediately began to consolidate his control.

One of Salemme's first moves was to persuade Raymond Patriarca Jr. that, as titular head of the New England mob, he had the clout to name Salemme as his Boston underboss. Although they believedâmistakenly as it turned outâthat Patriarca would not give Salemme the blessing he was seeking, Vinnie Ferrara and J. R. Russo waited to see which way Patriarca Jr. would go. They didn't have to wait too long.

In June 1989, Salemme was lured to a meeting outside a pancake restaurant in Saugus by Sonny Mercurio, a Patriarca gang member who later turned mob informant, and was ambushed.

Salemme was badly woundedâshot in the chest and legâbut he survived. Those responsible for the ambush were never prosecuted.

Then Patriarca Jr., in a half-baked effort to bring peace among the warring factions, approved a ceremony in which foot soldiers of both gangs would be inducted into the mafia. It was intended to be the most formal of ceremonies, with vows

of loyalty underscored with the sharing of blood from pricked fingers, but unfortunately for Patriarca, several members of the group crowded into the basement of a Medford residence owned by the relative of a mob underling were FBI informants.

To top it off, the whole ceremony was bugged by the Boston office of the FBI.

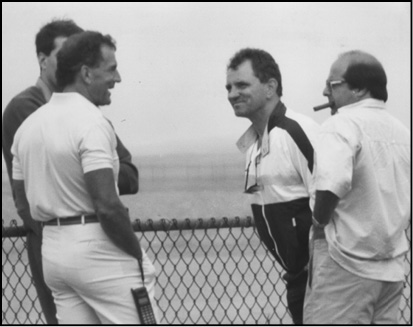

Frank Salemme led a criminal gang that sought to take over Boston's underworld after Gennaro Angiulo; his brothers were indicted and removed from the scene in the mid-1980s. Salemme is shown here (left, in white) with members of his inner circle, including Richard Devlin (second from right). Courtesy

Boston Globe

Patriarca began the meeting by saying that, to bring peace between the two groupsâSalemme's and the one Russo, Ferrara, and Robert Carrozza controlledâhe had agreed to make his stepbrother J. R. Russo his consigliere in Boston. Both sides would agree to abide by Russo's decisions, he told those attending. Then, with the FBI picking up the entire session through an extraordinary “roving bug” from outside the house, the ceremony began.

Each would-be mobster took the same oath in Italian, following the lead of Biagio DiGiacomo, the balding, pudgy-faced captain of the Patriarca family.

“I want to enter into this organization to protect my family and to protect all of my friends. I swear to not divulge this secret and to obey with love and

omerta

.”

Each inductee's trigger finger was then pricked, drawing blood for use in the ceremony. Eventually a holy card, with the image of the patron saint of the Patriarca family, was burned in the hands of each inductee.

“As burns this saint, so will burn my soul,” DiGiacomo read. “I want to enter alive into this organization and I will have to get out dead.”

Then, in an ominous, almost monotone voice, DiGiacomo stressed the importance of the secret oath taken by the inductees.

“It's no hope, no Jesus, no Madonna,” DiGiacomo warned. “Nobody can help us if we ever give up this secret to anybody. Any kinds of friends of mine, let's say. This thing that cannot be exposed.”

When it was discovered that the induction ceremony had been compromised by the FBIâcompounding the doubts the other families already had about Patriarca Jr.âthe son's hopes of controlling the New England mob evaporated. His only recourse was to “go to the mattresses”: an all-out war between the two Boston crime rings. The soldiers controlled by Salemme took on those controlled by Ferrara, Carrozza, and Russo, a gang known as the “renegade group” because they owed their allegiance more to the Angiulos in Boston than the Patriarcas out of Providence.

The hostility between the two gangs was so intense that it touched off more than a dozen murders and assassination attempts, and all efforts to bring peace following the attempt to kill Salemme in 1989 failed miserably. And when the innocent son of one soldier in the renegade group was killed fixing a flat tire, the situation only intensified.

“This was a very dangerous time,” said one member of East Boston's Rossetti family, which was loyal to Salemme.

“People were looking over their shoulder all the time. It wasn't good for business, and it wasn't good for anyone's health.”

Both sides drew up assassination lists of who was most vulnerable and in what order they should be hit, according to a 1994 indictment that resulted in the arrest of more than two dozen members of both gangs and put a halt to the outright warfare.

“I left right then,” the Rossetti family member told me, after hearing his name was on a list prepared by the Russo/Ferrara gang and two strangers showed up at his sister's house asking for him. “I went as far north as I could in New England, changed my name and never came back.”

_______________________

In the early days

of the war between the Salemme and Ferrara/Carrozza/Russo factions, as the two gangs tried to kill each other in shocking numbers to exert control over Boston's underworld, a few members in each camp shared a common secret: that the Gardner Museum was vulnerable to a theft.

The Rossetti gang, whose members were loyal to Salemme, knew by way of Louis Royce, the gay mobster who had slept inside the museum as a child.

After the theftâbut before Frank Salemme disappeared into the witness protection programâI asked a member of his family if Salemme might be able to shed some light on the theft and the whereabouts of the paintings. A few days later I got word back from Salemme.

“He says he doesn't know anything himself but would have to talk to Stevie Rossetti to know for sure,” I was told. At the time Rossetti was serving more than forty years in prison for bringing multiple weapons and bombs to the armored car heist he'd planned with David Turner and others in 1999.

And at least one member of the Ferrara/Carrozza/Russo gang knew because he had hung out with the legendary art thief Myles Connor and, with Connor, had cased the Gardner Museum back in the 1980s.

Although law enforcement and even the Gardner Museum had investigated countless leads over the years, the secret of who had actually pulled off the Gardner heist lay within these two gangs. At war since the mid-1980s, the gangs still shared connections. And those connections might just unlock the mystery of the March 1990 theft at the Gardner Museum.

The Missing Motive

O

n a Saturday evening in May 2014,

my home phone rang. I didn't recognize the number that showed up on my caller ID, so by habit I reverted back to my years as a

Boston Globe

reporter, giving my full name when I picked up. About a month before, I had written a letter to Vincent Ferrara, the former Boston gang leader, after hearing that he had told a lawyer I knew that he was interested in helping solve the Gardner mystery. After introducing himself, the caller, who asked to remain anonymous and identified as an intermediary to Ferrara, questioned what I knew about the Gardner Museum theft, and why I was interested in talking to Ferrara, whom he said he knew. Soon he sought my theory on the case.

“I've been at this a long time,” I told the caller. “But really, I just don't know. I'll tell you one thing, though; the FBI is damn sure they know.”

“Oh yeah?” the caller said.

I told him that as far as I could tell, the FBI was certain the heist had been arranged by David Turner, who had turned the stolen art over to Robert Guarente, who before he died in 2004 had given at least several of the paintings to Robert Gentile.

“Do you believe them?” the caller asked.

“I know there are holes in their story on all counts,” I replied. “But I don't see any reason for the feds to be lying about what they've come up with.”

“They don't know what they're talking about,” the caller said. “David Turner didn't have anything to do with this. If he did, he wouldn't be spending the best years of his life behind bars.

“Bobby Donati robbed the Gardner Museum,” the caller said flatly.

“Why would Donati pull off a heist like that in 1990?” I asked the caller.

“To get Vinnie Ferrara out of jail,” he responded.

_______________________

By the late 1980s,

Vincent Ferrara had ascended to the top level of a Boston-area group that was trying to assert control of the New England underworld. Although he'd been inducted into the Patriarca family and was regarded as a cunning strategist and fierce enforcer of the mob's rules, Ferrara was a different sort from his brothers in his own gang, not to mention the gang headed by Frank Salemme that he was battling for control.

Ferrara hadn't grown up around the mob, like most of his consorts. In fact, once upon a time Ferrara had been headed for a career in finance. Then he started hanging around with the toughs in Boston's North End. After he was convicted for illegal possession of a firearm in the mid-1970s, his chances of

convincing legitimate people to trust him with their money evaporated and he turned to offering protection to bookies, loan sharks, and their brethren.

Even more unusual in his line of work, Ferrara was different in how he maintained his personal life. He was obsessed with healthy living. He'd never smoked and had avoided eating red meat since the late 1970s. He worked out religiously, was a voracious reader, and was a good enough high school student to have been accepted at Boston College, where he'd graduated with a degree in finance. But more akin to his fellow mobsters, he maintained strict adherence to the mafia code that all key decisions and conflicts were to be handled by the heads of the families, and that its members were strictly forbidden from engaging in drug trafficking.

According to those who knew him, Ferrara told of conversations he had had with mob boss Jerry Angiulo on how he should conduct himself if he expected to succeed in business or in the mob. “Don't do business with anyone unless you think he's as strong and smart as you are,” Angiulo had told him, according to one Ferrara associate. Ferrara heeded that advice, believing the old man meant that while anyone can be your partner when times are good, when things get screwed up, you want to be sure you've got someone beside you who isn't going to panic and who is going to back you up no matter what you decide to do.

The war between the two gangs had been going on since US prosecutors had indicted the Angiulo brothers on multiple counts of racketeering in 1985.

Jerry Angiulo and his brothers had maintained an iron grip over Boston's bookmaking, loan-sharking, and other criminal activity since Raymond Patriarca had anointed him as underboss of most of New England's organized crime activity in the early 1970s. Secret tape recordings of the North End office Angiulo used to run his criminal enterprise proved

to be his undoing. In conversations intercepted by the FBI, Angiulo bragged to Ilario Zannino, his consigliere, of his organization's powerful reach and his belief that he and his associates couldn't be indicted for racketeering, believing the offense applied only to the illegal takeover of legitimate businesses and not of illegitimate ones.

“Our argument is we're illegitimate business,” Angiulo told Zannino, describing the legal defense he would raise to any indictment. “We're shylocks,” Zannino agreed.

“We're shylocks,” Angiulo echoed. “We're fuckin' bookmakers.”

“Bookmakers,” parroted Zannino.

“We're selling marijuana,” Angiulo picked up.

“We're not infiltrating,” Zannino added.

“We're illegal here, illegal there,” Angiulo continued. “Arsonists. We're every fuckin' thing.”

“Pimps, prostitutes,” Zannino picked up.

“The law doesn't cover us,” Angiulo stated boldly. “Is that right?”

“That's the argument,” Zannino replied.

Angiulo turned out to be wrong and the feds convicted him of an avalanche of criminal charges. In February 1986 he was sentenced to forty-five years in prison. Angiulo died in 2009 following his release from federal prison. The battle between Salemme and Ferrara to succeed Angiulo as Boston's crime underboss began almost immediately after his conviction. Raymond Patriarca had died two years before, so there was no ultimate authority to choose a successor. The decision would be made by the power of the gun.

It was under these circumstances that Frank Salemme was nearly killed, and soon thereafter, Raymond Patriarca Jr. held the ill-fated cease-fire talks that the FBI secretly recorded. Rather than re-securing Patriarca's hold on the Boston underworld, the events of that day essentially guaranteed his fall from power.

For his part, Ferrara was undone by a different set of tapes. In early 1987, he summoned two aging bookies, Moe Weinstein and Harry “Doc” Sagansky, to Vanessa's, a mob-friendly restaurant in downtown Boston. There he informed them that the old ways of doing things under the Angiulos were changing. No longer would they be allowed to operate their booking operations rent-free.

Both would need to pay $1,500 each month in tribute to Ferrara, and each would need to come up with a $500,000 payoff just to stay in business.

“I'm not making that kind of money,” Doc Sagansky, who had operated a bookmaking business in Boston for fifty years, told Ferrara. His traditional moneymaker, the daily three- and four-digit numbers games, had been made obsolete by the state-run Massachusetts Lottery.

“What I'm driving at,” Sagansky told Ferrara plainly, “is that the business has been destroyed. You pick up the paper and look at the payoffs on the four numbers and three numbers, and the four numbers is almost 100 percent more if you play with the lottery. . . . I don't know if you ever look at it. We look at it because . . .”

Ferrara finished the sentence for him. “It's your business.”

As it turned out Sonny Mercurio, Ferrara's close friend and the best man at his second wedding, had turned FBI informant and had arranged for the feds to secretly tape Ferrara's meeting with Sagansky and Weinstein. The tapes would ultimately be the underpinning of the racketeering indictment against Ferrara and eight others.

But the tapes weren't Ferrara's only problem. He was also indicted for ordering the murder of Vincent “Jimmy” Limoli, whom federal prosecutors tried to show Ferrara wanted killed because he had persisted in selling drugs in the North End. Ferrara's lawyers claimed that the prosecution's lead witness on the murder charge was lying about Ferrara's involvement

but it would take twenty years and the unearthing of long-buried government files for that defense to be upheld.

In the early 1990s, however, Ferrara, who was forty at the time, was convinced that he faced a life sentence if he went to trial on the murder charge and was convicted. Believing his only recourse was a plea deal, he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and in 1992 he was sentenced to twenty-two years in jail.

Bobby Donati was one of the first people to visit him in jail. The two had been close for nearly a decade, as Ferrara was growing in power in the Boston underworld, and when Ferrara needed someone he could trust to be his driver, he picked Donati.

Donati was the perfect wheelman for Ferrara. The two had spent hours at a time together in Donati's red Mercedes two-seater through much of the 1980s, and Donati, a perennial jokester, kept the conversation light. That is, except when he was broke, which was most of the time, and he was looking for advice from Ferrara on whom he could tap for a quick loan or to find an easy score. Donati had an appreciation for the finer things in life, including oriental rugs and antiques, and spent many weekends visiting museums, galleries, and second-hand shops with his son.

But that day in the federal lockup in Hartford, where Ferrara was first taken after his arrest, Donati was deadly serious, according to a source who knew both men.

“I can't let you stay here,” Donati told Ferrara, keeping his words clipped and vague as both men knew that conversations between prisoners and their visitors were likely tapped, according to the source. “I'm going to get you out of here.”

“What are you talking about?” Ferrara asked Donati. “Don't you do anything. No matter what you do, it's not going to get me out of here.”

“They will for these; you'll see,” Donati said.

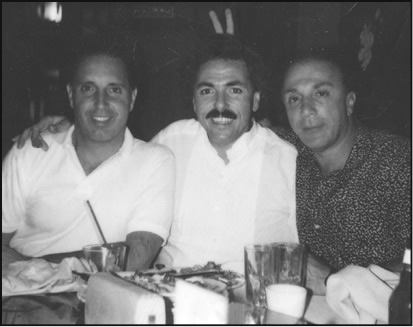

Vincent Ferrara (left) and Robert Donati (right) enjoy a meal with an unidentified third man sometime before Ferrara was arrested for racketeering in November 1989âthree months before the Gardner Museum was robbed. Donati allegedly told Ferrara he arranged the heist to assist in bartering for Ferrara's release.

“Bobby, don't do this,” Ferrara implored, according to the source. “Whatever it is you've got planned, do not do it. You're just going to get yourself in trouble. Besides, they're not letting me out of here no matter what you're offering.”

But three months later, Ferrara read the news that two men dressed as police officers had stolen thirteen pieces of art, including several masterpieces, from Boston's Gardner Museum, and he knew immediately who was behind it.

Ferrara had been moved back to Massachusetts and was incarcerated in the Plymouth House of Correction when Donati came to see him. “Was that you?” he asked Donati, the source recounted.

“I told you I was going to do it. Now I got to find a way to begin negotiating to get you out,” Donati responded.

“You're insane,” Ferrara responded, remembering that the headlines had said the Gardner heist might be the largest art theft ever and that the FBI had more than forty agents scouring

Boston's neighborhoods for clues. “They're not going to do any deal where they have to let me out. They want me locked up forever, now more than ever,” the source said, quoting Ferrara.

The Justice Department was indeed intent on eliminating Boston's mob. US attorney general Richard Thornburgh and FBI director William Sessions had even traveled to Boston in a government jet to announce the indictments, saying they represented the most sweeping attack on a single organized crime family.

“The case is important in that it represents a stake in the heart of a major organized crime family from the boss on down,” Thornburgh said at a press conference. “It establishes beyond doubt the existence of a secret clandestine operation that takes itself very seriously in terms of the illegal operations it carries out.” Although the press conference took place eight days after the Gardner theft, nothing was said about the status of the investigation.

But the heist was certainly on Ferrara's mind when Donati sat across from him at the Plymouth jail. “Bobby, you're going to bring more heat on yourself than ever before,” Ferrara said, actually sounding genuinely concerned for his fellow mobster. “For your own good, I'm telling you to get out of town. Go to Florida. Anywhere. But get out of town.”

“Don't worry about me,” Donati said, seemingly unfazed. “I've buried the stuff. Once this blows over, I'll find the right person to negotiate with.”

Donati never got that far. He was brutally murdered in September 1991, sixteen months after the theft. The FBI had him under continuous surveillance at the time. It is possible the feds believed he was a vulnerable target in Boston's ongoing gang warâor they may have been looking at him as a suspect in the Gardner case.