Mastering the Craft of Making Sausage (11 page)

Read Mastering the Craft of Making Sausage Online

Authors: Warren R. Anderson

Tags: #Methods, #Cooking, #General, #Specific Ingredients, #Cooking (Sausages), #Sausages, #Meat

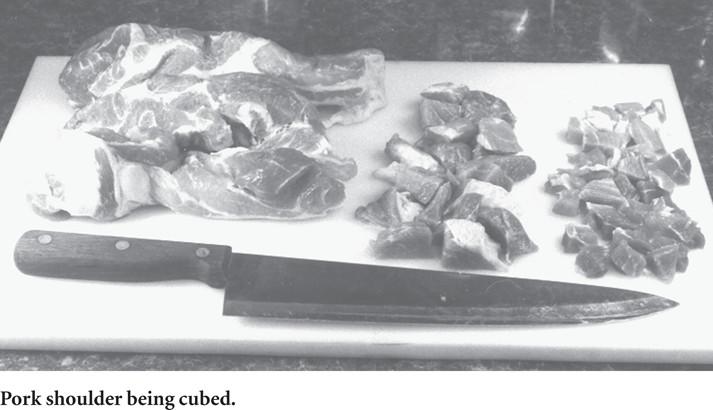

It is best to cut a large hunk of meat into slabs about ¾ inch (2 cm) thick, and then proceed to cut the slabs into ¾-inch (2 cm) cubes. A medium or large chef’s knife with a stepped blade works best for cubing. The size and shape of the cut meat is not critical; the sole purpose of cutting the meat is to prepare pieces that will go into the hopper of the grinder easily. It is not important for the pieces of meat to have a cubical shape.

After weighing and preparing the correct amount of each kind of meat and fat, return the cubes to the refrigerator until they are thoroughly chilled. In fact, anytime the meat is not being worked on in some way (trimming, cutting, grinding, stuffing, smoking, etc.), it should be chilling in the refrigerator. Because this is so important, most recipes in this book suggest that the meat should be refrigerated after certain steps.

Here is a hint that is not mentioned in most of the recipes

: If you want to proceed to the next step soon, and you want the chilling to be accomplished as fast as possible, put the meat in the freezer rather than in the fridge. It should not stay in the freezer long enough to freeze, but no harm will be done if the bulk meat, the cubes, or the ground meat is a little crunchy on top.

Grinding the Meat

Note: It might be helpful to review the section “Meat grinders (meat choppers or meat mincers)” in Chapter 2.

A food processor can be used to shred the meat. If you have a powerful food processor, you might wish to try it. However, if a food processor is used, small amounts of meat should be shredded at a time; this will reduce the strain on the machine. Be careful not to process the meat too long—the particles will be too fine.

Even though a food processor will do the job quickly, a meat grinder will provide a better texture because it will mince or chop the meat instead of shredding it. A meat grinder will also allow the fat to be ground finer or coarser than the red meat; this is necessary for some sausages.

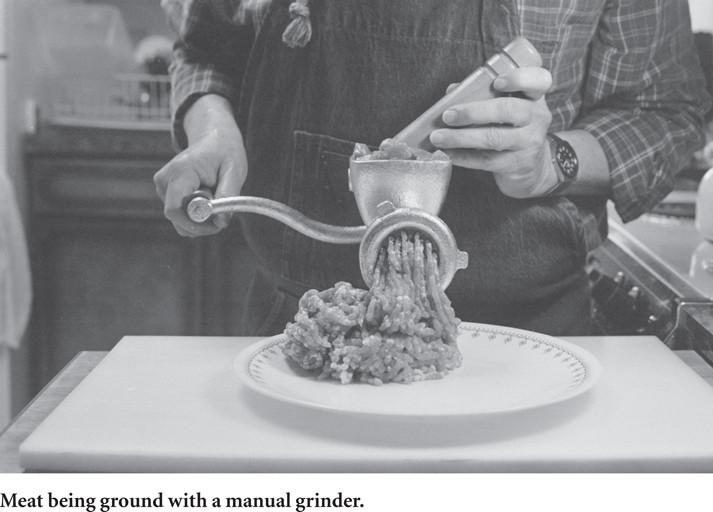

All meat grinders work in the same way, whether they are powered by arm muscle or electricity. The desired plate (fine, medium, or coarse) is placed in front of the knife (chopping blades), the collar is screwed on tightly, cubed meat is stuffed into the hopper, and the handle is rotated—or the switch is turned on. That is about all there is to it, but a few pointers may be helpful, and a few techniques may be useful.

When the meat is ground and the particles are extruded from the holes in the plate, the stream of particles coming out of each hole should be distinct from the other streams. If the streams blend into a sticky mass or look mushy, this is called

smear,

and grinding should stop until the problem is corrected. There are three possible causes for smear:

• The meat is too warm. It should been chilled to almost the freezing point. However, fat can be ground when it is frozen. Chill the meat and try again.

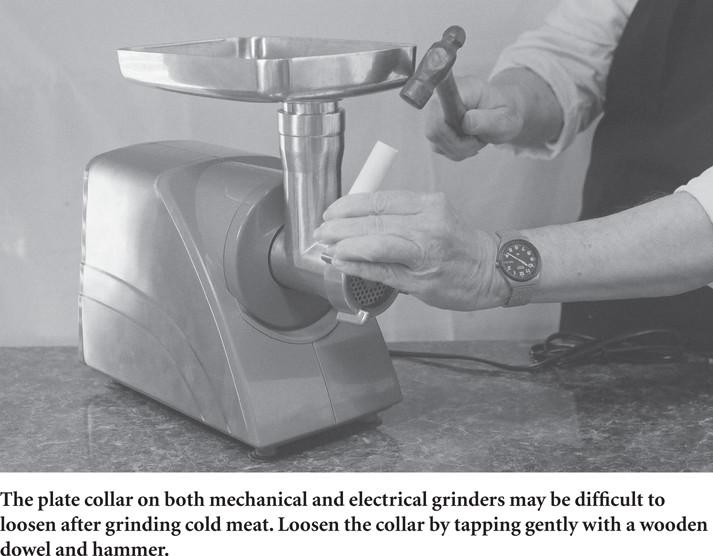

• The collar that holds the plate and chopping blades together is not tight. Tighten the collar.

• Sinew and other connective tissues are clogging the holes in the plate, or they are tangled around the chopping blades and plate. Unscrew the collar, clean the plate and chopping blades, and reassemble. Make sure the sharp edges of the blades are flat against the plate.

Some sausage makers separate the fat and the red meat, and they grind the fat a little finer than the muscle meat. The theory is that if the fat is fine, it will be more evenly distributed in the sausage, and less fat can be used to achieve the same taste. The theory sounds plausible, but when fat is ground without being mixed with muscle meat, the ground fat tends to clump together, and separating the clumps into particles is tedious. Techniques for dealing with this problem will be explained a little later.

There is another reason for grinding the fat finer than the muscle tissue. Coarsely ground muscle meat has less surface area than the same weight of finely ground muscle meat. Consequently, less fat is required to moisten the surface of the muscle meat particles if the particles are large.

The technique I use for most sausage grinding is easier than grinding the fat separately, and I think it gives about the same results. I roughly separate the meat and the fat, cut the meat into ¾-inch (2 cm) chunks, and cut the fat into smaller chunks. Then I mix the meat and the fat together and grind it. This technique helps to reduce the tendency of the fat to clump, and distributes the fat very well. After grinding, however, the meat and fat particles are the same size.

For common sausages, most people use neither one of the techniques mentioned above; they grind all the fat and muscle meat together without making any special effort with the fat grinding or distribution.

However, for some sausages, a very special effort must be made when working with the fat. Salami and some Asian sausages must have very noticeable specks of white fat. Mortadella has cubes of fat mixed with a sausage paste that looks much like the sausage paste for bologna. This highly visible fat in certain varieties of sausage helps to define the kind of sausage. If it does not have the white specks, for example, it is not salami. If it does not have cubes of fat mixed with the sausage paste, it is not mortadella.

No matter how you are grinding the meat, when you get to the end of the grinding session, there may be hunks of meat and fat just behind the plate that the auger was not able to push into the path of the chopping blades. Ignoring this meat and discarding it is the easiest thing to do, but it may be wasteful. If there is some useable meat behind the chopping blades (much of this will be unusable gristle and sinew), it can be minced with the chef’s knife and added to the sausage mixture.

Mixing the Meat and Ingredients

After the meat has been ground and is chilling in the refrigerator or freezer, the seasoning and other ingredients are prepared and blended.

It is important that the finished sausage paste be perfectly blended and uniform before it is made into patties or stuffed. This goal is likely to be accomplished if all the seasoning ingredients are uniformly blended before the ground meat is added. Also, it is easier to accomplish this if at least one of the ingredients is a fluid: water, wine, broth, beer, juice, etc. The fluid dissolves, or partially dissolves, most of the other ingredients, and it acts as a carrier to spread the ingredients uniformly throughout the ground meat.

All the sausages in this book are prepared in this way; all ingredients except the ground meat are blended first, and this blend is always a thin paste or a viscous liquid. This seasoning should be prepared in a mixing bowl large enough to mix in the meat—at least a 5-quart (5 liter) bowl if 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) of sausage will be made. No matter where a recipe is obtained, it is an easy matter to change the recipe so that all seasoning ingredients are mixed with water or some other liquid before blending with ground meat. If this procedure is followed and the meat is blended properly, the taste of the entire batch of sausage will be uniform. If a recipe from another book, from the Internet, or wherever says to sprinkle the seasoning on the ground meat and mix it, this may result in some sausages tasting differently from other sausages in the same batch. For best results, change the recipe so that the spices and other ingredients are mixed together with a liquid before the ground meat is added.

The fluid-seasoning blend should be chilled before the ground meat is mixed with it. While the ground meat and the seasoning blend are being chilled, it is a good time to take a well-deserved break. Or, if you still have energy, use this time to wash the meat grinder and put it away; final cleanup will be faster and easier if that is done.

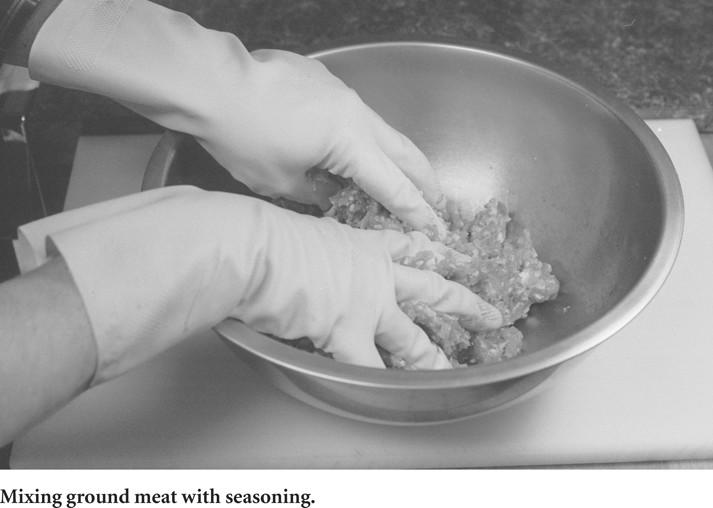

After the seasoning mixture is thoroughly chilled in the large mixing bowl, add the ground meat to the same bowl. The ground meat and seasoning paste must be mixed with the hands or with a heavy-duty standing mixer. Mixing with a wooden spoon, or the like, requires much energy, is tedious, and it will not do the job.

After one or two mixing sessions, mixing up to 5 lbs. (2,270 g) of sausage by hand becomes very easy. For sanitary reasons, and to insulate the hands from the ice-cold meat, it is best to wear rubber gloves. First, flatten the mixture in the bottom of the bowl with your fists, then fold it in half, and flatten it again with your fists. Next, spin the bowl about 90 degrees clockwise by twisting the fists, fold the mass again, and flatten it again with your fists. (It is a type of kneading process—similar to kneading dough.) Continue doing this until the ground meat and seasoning mixture looks uniform. From start to finish, mixing by hand will require about three minutes.

If a mixer is used, it should be something like an upright 5- or 6-quart (5 to 6 liter) KitchenAid mixer with a paddle attachment. (Please see

Food mixers

in Chapter 2.) Mix for about one minute at slow speed and one minute at medium speed.

The friction involved in mixing the sausage generates heat, so the sausage needs to be thoroughly chilled again in the freezer or refrigerator before making patties or stuffing into casings. The making of patties or stuffing should be done the same day, however. If the bulk sausage is allowed to set in the refrigerator overnight, the salt causes the mixture to become stiff, and it will be difficult to stuff.

Preparing the Natural Casings

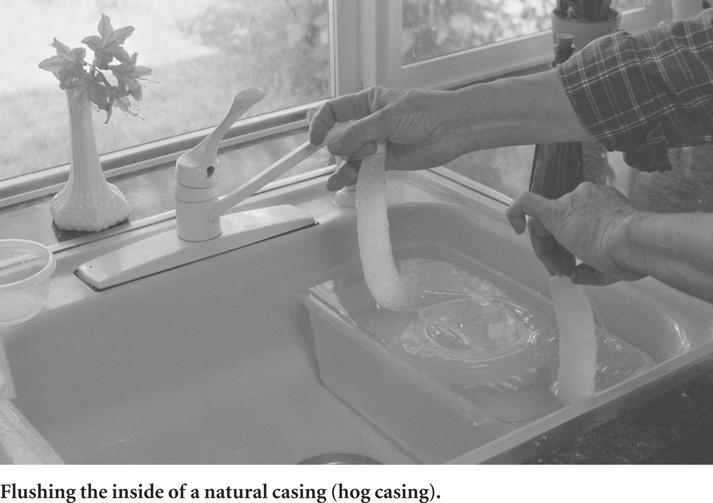

For home use, it is best to purchase casings that have been packed in salt; such casings can be preserved for years under refrigeration. If, however, you are using casings that have been packed in a preservative solution, they can be used immediately after a brief rinse; the preparation steps below need not be followed. Unfortunately, these casings have a shelf life of only about one month.