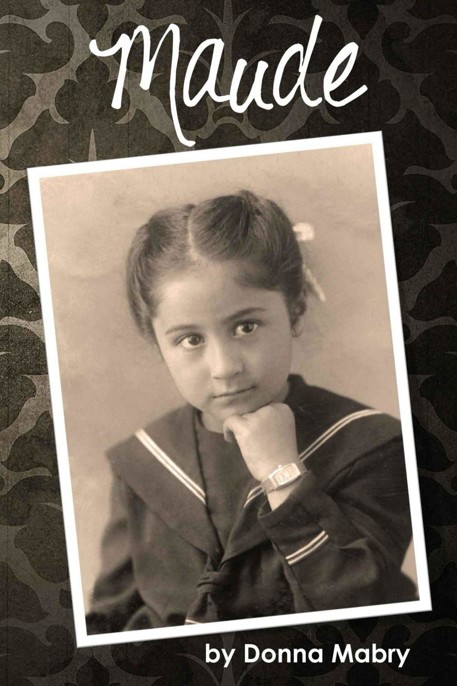

Maude

Authors: Donna Mabry

by

Donna Mabry

Acknowledgements

I owe a debt of gratitude to many people for their

help with this book:

I thank my sister-friend Shelby Turnbull

MacFarlane, who is the witness to my life. She knows

things about me that even my children don’t. She

helped me with some of the research to call up details

in places where my memory was fuzzy and retrieved

documents to verify the story of my aunt’s death.

My editors: Lawrence Montaigne, Elaine Stubbs,

Scotty MacFarlane, Maryann Unger, and Phil

Schlaeger from Anthem Authors. The story is much

better with their assistance.

Barbara Winters, Jeane Harvey, Judy Kuncewicki

and Lawrence Montaigne, my proofreaders, who not

only make corrections, but who encourage me

constantly by reading my work.

Sandy Novarro, who now has a shelf full of

things she told me to write.

And my daughter, Melanie Mabry, who wanted

to hear this story in the first place. Boy, is she in for a

few surprises.

My parents divorced when I was three, and my

mother left me to be raised by my maternal

grandparents. For the next nine years, whenever he

wasn’t working overtime, my daddy came to get me

almost every Friday night and every school vacation.

He returned me to my grandmother’s custody the last

possible day.

My earliest memory is a winter morning when he

carried me to her house, my cheek resting against the

chilly smoothness of his brown leather jacket. I was

his almost every weekend, in summers from June to

September, and over spring and Christmas vacations.

I shared my grandmother’s room. She would read

me to sleep each night, not with stories out of books,

but with the spoken stories of her life. As we lay there

in the darkened room, I struggled to stay awake to hear

the amazing things she had to tell. At the same time,

her soft voice was a lullaby inviting me to sleep. I

wonder now if she found it her personal therapy to

murmur her burdens in the darkness to a very

interested listener.

As I grew older, and she felt I could understand

them, she revealed more of the intimate details, until

finally, when I was sixteen or so, she even talked about

what part sex played in her life.

She didn’t go in chronological order, but spoke

of whatever came to her mind. One night she would

talk of her childhood, another of the wars or the

depression. Sometimes she talked about losing four of

her five children.

It wasn’t until many years later when I repeated

some of these things to my daughter that I fully

realized how epic a tale my grandmother’s life had

actually been.

it down for me?”

the great-grandmother that she knew only as an infant.

A small part of what I have written here is

fictionalized, and some of it falls back on my own

memories of later events, which may be biased. I have

included some of my grandfather’s comments, but he

mostly joked about things and wasn’t a serious person

like my grandmother.

Evelyn, my mother would tell you a different

story, but I am representing my grandmother’s point of

view.

The greater substance of this, and many of the

direct quotes, are written in my grandmother’s words,

and are what I heard from her during those long-ago

nights we shared a bed.

Prologue

I was barely over fourteen years old, and it was

my wedding day. My older sister, Helen, came to my

room, took me by the hand, and sat me down on the

bed. She opened her mouth to say something, but then

her face flushed, and she turned her head to look out

the window. After a second, she squeezed my hand and

looked back in my eyes. She stopped, dropped her

gaze to the floor, and then said, “You’ve always been

a good girl, Maude, and done what I told you. Now,

you’re going to be a married woman, and he will be

the head of the house. When you go home tonight after

your party, no matter what he wants to do to you, you

have to let him do it. Do you understand?”

I didn’t understand, but I nodded my head

anyway. It sounded strange to me, the way so many

things did. I would do what she told me. I didn’t have

a choice, any more than I had a choice in being born.

I came into this world as Nola Maude Clayborn in

1892, in Perkinsville, in the northwest corner of

Tennessee, a few miles west of Dyersburg. Pinned to

the ground by a church spire at each end of the road

that cut the town in half, Perkinsville was barely a

wide space in the road. The houses were so far apart it

was almost country. It was made up mostly of farmers

and the businesses that served them.

Most of the houses had a barn in the back for one

or two horses, and a buggy to ride in or a wagon for

farm work. We all had chickens, and a cow for milk.

Every house had a vegetable garden, and most of them

had some sort of orchard with apple, cherry, and pear

trees.

There was one general store and one doctor. A

widow in town sometimes rented out sleeping rooms

to travelers, but there was no hotel, no restaurant, no

bank, and certainly, no saloon. Almost everyone still

raised their own chickens, hogs, fruit and vegetables.

I remember it partly by its smells. Walking

through town in the winter, I could smell the smoke

from the wood burning fireplaces and stoves, the farm

animals, and if the wind was right, the stink of the

chicken coops. In spring, the air was heavy with the

sweetness of fruit blossoms and freshly turned soil.

There was a Baptist church to the east end and a

Holiness church to the west. My family was Holiness,

and our lives revolved around our church. We went to

meeting Sunday morning, Sunday night, and

Wednesday night. Once a year, there would be a

visiting preacher, and a revival that would go on every

evening for a week.

The steeples of the two churches served as a sort

of city limits. You could walk from one church to the

other in less than a half-hour. There were no Catholics

and no Jews, and most of us didn’t even know that

there was any such thing as an atheist. Not one person

there would even have understood what an atheist was,

except maybe the doctor. He had more education than

most, and had lived in other places until he was in his

sixties, when his wife died, and he gave up his practice

in the city to come back to live where he grew up.

Most folks in my town were born there and died

there and maybe took one trip to Memphis on their

honeymoon.

down the road, a short distance from the larger part of

town.

In looks, I took after my father, Charles Eugene

Clayborn, with straight brown hair, and brown eyes. I

was big for my age and built sturdy, like my daddy.

My sister, Helen, was eleven years older, and

took after our mother, Faith. They were both small and

trim. Daddy used to say they weren’t as big as a

minute. They were fair, with sparkling blue eyes and

hair of a pale blonde shade.

Helen’s hair hung in waves over her shoulders,

but Momma wore hers pinned up in a bun at the back

of her neck, the way all the married women did. I loved

the way little wisps of curls would escape the pins.

When Momma was outside, they would flutter in the

breeze, like butterflies dancing on her neck.

Helen had an hourglass figure, and the neighbors

used to say that she had a waist a man could clasp his

hands around. Those ladies would smile kindly at me

and pat me on the head as if to comfort me. I hated

that. I knew early on that I was plain. I got used to it.

My mother fussed over Helen all the time, making her

pretty dresses, tying ribbons in her hair. Other than

telling me what to do, she didn’t pay me any mind.

It really didn’t bother me all that much. I was a

daddy’s girl. He ran the livery stable directly across the

street from our little house. He trained a few horses to

sell, rented out horses and buggies, and boarded

traveler’s mounts. He was up and gone to tend the

stock before I got out of bed in the morning.

When he came home for dinner he would give

Momma a kiss and then scoop me up in his strong arms

and give me a big hug. Then he’d sit me on his knee

and talk to me, just me, until dinner was on the table.

He’d look down at me and smile, and ask me about

school and my friends. He’d tease me about liking

James Connor, who lived down the road from us.

Daddy was a big man, his chest and arms thick

with muscles from lifting bales of hay. I’d lean my

head against his chest and smell the horses and the feed

on him. I found the only comfort there was for myself

in his attention. He was my world.

After dinner, he would go back to the barn to

settle the animals for the night. I was usually asleep

when he got back. It was precious little time he was

able to give me, but it was enough.

As 1899 came to an end, everyone was excited

about the New Year, 1900, and a new century. I found

the number interesting, but didn’t see what all the fuss

was about. Wouldn’t things be just the same the day

after as they had been the day before? It was all people

talked about for weeks. I listened to them at school and

at church and at the store. I didn’t really feel it had

anything to do with me. I didn’t think the coming

century would change my life much, but it did. That

year turned my life upside down.

I was seven, and Helen eighteen, in April of

1900, when Helen married Tommy Spencer. He was

one of the nicest young men. His parents owned the

general store, and they were about the richest family

in town. Helen packed up her things and moved to the

pretty little house Tommy had built just for her. It had

a porch all the way across the front, like ours, with

another one across the back so you could sit in the sun

or the shade at any time of day. Tommy had a water

pump right there in the kitchen so Helen wouldn’t have

to go outside to get water. There was a washroom in

the back, a bedroom on each side, and a parlor in the

front.

People kept trying to make me feel better about

being alone after Helen married, but I didn’t miss her

all that much. I visited her from time to time and saw

her at church every meeting. Her moving out meant

that I had a room of my own, and my life was quieter

without the young people that hung around my sister.

Before she left, it seemed to me that they were always

at the house. Helen’s girlfriends were there almost

every day after school. They sat on the front porch,

drinking iced tea and giggling and whispering into one

another’s ear about some boy or the other, mostly

things that they didn’t want me to hear.

The boys made up excuses to stop by, asking

about school or church, falling quiet if I came in

earshot. My sister’s friends either looked at me like I

wasn’t welcome, or looked right past me, as if it

weren’t my porch, too, or my house, as if I didn’t have

any right to be there.

With Helen married and gone I got real attention

from my mother for the first time that I could

remember. She set about the job of making me a fit

wife for some man, someday. We planted the spring

garden together, rows of lettuce, greens, tomatoes, and

corn. She talked to me all the while in a way she never

had before, like I was a grown-up. We hoed the

ground, and she showed me how to poke my finger

into the soft soil to make a little hole to drop the seeds

in one at a time. With Helen out of the house, Momma

and I became a team.

We cooked together in the kitchen on the big

wood-burning stove, with me standing on a little stepstool my Daddy made for me. I got to mix the sugar

and spices for the apple pies, and watched how Mom

rolled out the piecrust, talking all the while about how

to use the coldest water to mix the dough.

She taught me how to listen for the sound of the

chicken frying in the pan, how when the sound of the

cooking changed from a murmur to a crackle, it was

time to turn it over, how to salt the potatoes before I

cooked them and the chicken after. She showed me

how to make light dumplings and good biscuits.

In the fall, I learned how to can fruits and

vegetables from the big garden my mother kept. I wore

an apron, folded up in a pleat at the waist to make it

fit, and sat at the table stringing the green beans,

popping off the top end the way she showed me, and

pulling the strings down to the bottom, then snapping

the bean into four sections. Mom put them in the big

pot on the stove with some fatback bacon, where they

would cook all day before they went into the Mason

jars.

In the afternoons, we would sit on the porch

where the sun shone bright and sew. Mom showed me

how she cut the fabric so there wasn’t much waste.

When she finished cutting out a dress, she could hold

the scraps in the palm of her hand. She taught me how

to make tiny, even stitches that wouldn’t pull apart, and

how to pull the thread over a candle before I started

sewing so it wouldn’t tangle. I learned how to knit,

crochet, and embroider a chain stitch, and to make

flowers and an alphabet with the needle.