Memnon (9 page)

Authors: Scott Oden

“My father often sang the praises of his city,” Memnon said, his voice carrying, “but it was the courage, the gallantry, of men like Glaucus and Bion, and all the others who fell with them, which made her splendid. No words suffice to do justice to their deeds. Doubtless each of them had their faults—we all do—but whatever harm they did in their private lives has been erased by their courage. They go to the gods clothed in white, and wreathed like victors at Olympia.”

Memnon paused and looked back at the flames. In his armor, sword at his hip, the son of Timocrates could have stepped from the poet’s verse, a living Achilles—ferocious, touched by the gods, perhaps even a little mad. The eyes of the audience never left him; they waited in rapt silence for him to continue.

“I have no wish to make a long speech; truthfully, I have not the stomach for it. Those men who fell defending my father, defending their belief in democracy, were the best of men. Rhodes will not see their equal for a generation. Does that mean we who survived are of a lesser quality? In many ways, I believe so, yes. But, as we are alive, we can learn, and we have the unique opportunity to remake ourselves, to become better men. I urge you all to embrace the lesson my father taught. Timocrates was a harsh man, but he was fair. Like the Athenians he admired, he did not let his love of the beautiful lead him to extravagance, nor did his love of things of the mind make him soft. He regarded wealth as something to be properly used, rather than as something to boast about, and he befriended all: rich, poor, healthy, infirm, pious, blasphemous, judging them not by the contents of their purse, but by the quality of their character. When the trials of the coming days leave your spirits heavy with sorrow or fear, remember the example set by these men, remember their valor, their sacrifice, and let it inspire you to find the best and bravest in yourselves.”

The heart of the pyre collapsed, sending a shower of sparks skyward. Memnon glanced up, watching as each ember blazed like a tiny star. Some vanished a moment after their birth while others endured, drifting high over the fire that spawned them.

Like men.

With a weary smile, Memnon returned his gaze to the people around him.“I have said enough. With the dawn, I leave Rhodes and my father’s bones come with me; this island is our home no longer. But, for tonight, let us gather as kinsmen. Let us speak kindly of the dead and give our grief free expression. Join me, brothers and sisters, raise your voices with mine so Lord Hades will know that men have come unto him this night, and he will know to honor them as we have.”

I

NTERLUDE

IA

RISTON SAT IN SILENCE AS THE WOMAN’S VOICE TRAILED OFF AND

her breathing softened. He glanced out the window, surprised to see night had fallen. The rain must have ceased sometime before dusk; now, a damp chill permeated the room. The young Rhodian rose and added a few logs to the glowing embers on the hearth, stoking it with a poker of blackened iron. The dry wood blazed, sending a shower of sparks up the chimney.

Burning bright, like the souls of men.In the renewed light he watched Melpomene as she slept, her face drawn and haggard from the exertion of tale telling. Despite being born some thirty years after the fact, much of what she spoke of was familiar to Ariston. His grandfather and namesake, a ship’s carpenter from Lindos, lived through the War of the Allies (as the Athenians called it) and the Carian occupation, though he loathed speaking of either. Only in his last years, when his mind began to fail, would he delve into the past and talk of friends long dead, deeds long forgotten; he would wake from naps trembling in fear, and hoard bread from his evening meal in expectation of some half-remembered famine. In his rare moments of lucidity, he would regale his grandson with tales of Athens, of Demosthenes, and of the Greek world’s struggles against that fearsome tyrant, Philip of Macedonia.

Melpomene groaned in her sleep, clutching the small silver casket tight against her side. She wheezed something in Persian. Twice during the day, Harmouthes had brought them possets of honey-sweetened wine, spiced and warmed; doubtless hers contained additional herbs to combat her illness.

Who is she?

Ariston searched his memory for fragments of information, tiny scraps he might have overheard and filed away. Unfortunately, he knew very little about Memnon of Rhodes, save that he contested Alexander’s presence on Asian soil. That Melpomene knew the man intimately was a given, but how? She was Persian; Memnon was Greek, which ruled out any blood connection. A wife, perhaps?Ariston finished tending the fire, straightened. When he turned to collect his belongings, he noticed Melpomene’s eyes were open now, moist and shimmering in the firelight.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I did not mean—”

“You remind me of my son.” Her voice barely rose above a whisper.

“He should be here at your side, madam, to help care for you. Is he aware of your illness? If you’d like, I can try to get a message to him.”

“I wish you could.” With some effort, Melpomene rolled onto her side, away from Ariston, and buried her face in the coverlet. Unsure of what to say, or of what he had said, Ariston picked up his bag and crept from the room. He met Harmouthes in the hallway.

“She sleeps?” the old Egyptian said.

Ariston nodded.

“Good. Come. I have taken the liberty of preparing you a light supper. You will stay the night, of course?”

“Yes,” Ariston said. “I’ll stay.” In truth, where would he go?

Harmouthes smiled. “Her story, it is infectious, is it not?”

“More so than I would have imagined.”

Ariston followed the old Egyptian to the kitchen. It lay off the peristyle, and like the Lady’s room, it too showed signs of repair, with fresh plaster on the walls and new mortar on the hearth. Enough supplies to maintain a much larger household cluttered the corners: sacks of grain, onions, and dried dates, bunches of garlic, pottery jars of honey, and a half-dozen large shipping

amphorae,

the kind used to transport wine and olive oil. A savory incense of stewed vegetables, herbs, and pork filled the air, bubbling from an iron pot hanging over the fire. The smell reminded Ariston he had not eaten in hours; his growling stomach reminded him he had not eaten well for some days. Harmouthes gestured to a table of age-polished oak, directing Ariston to take a seat.The Egyptian bustled about the kitchen, setting out a platter of cheese, dates, and bread, with a small bowl of oil for dipping. He drew wine from one

amphora,

enough for the both of them, and finally spooned a helping of stew into a bowl for Ariston. The young Rhodian smiled his thanks and attacked the food with gusto. Harmouthes eased himself onto the bench across from him, poured two cups of wine, and selected a date to nibble on.“Who is she?” Ariston said around a mouthful of bread. “Your mistress, I mean.”

Harmouthes shrugged. “She is one who knew Lord Memnon and who believes the Macedonians do a great injustice to his memory.”

“That much I gathered. Her knowledge of him is the knowledge of an intimate. Was she his wife?”

“A woman of court,” Harmouthes said, averting his eyes. “Nothing more.”

Ariston paused to down a gulp of wine. “I may be young, Harmouthes,” he said, wiping his mouth with the heel of his hand, “but I’m not stupid. If Melpomene is only a woman of the court, why all this secrecy?”

“Consider it a by-product of our times. The Macedonians do not foster an atmosphere of openness. If my mistress desires to hide her identity for the time being you should honor her wish. Truly, she is not seeking to deceive you, only to protect herself.”

“From whom?”

Harmouthes gave the young Rhodian a weak smile. “You are tenacious, I give you that. I am weary, and I must check in on my mistress before bed. I am sorry we cannot offer you more palatable accommodations, but this hearth will have to do. Help yourself to whatever you see—wine, bread, more stew. Is there anything else you require?”

“Answers, but I see those won’t be forthcoming tonight.”

“Perhaps tomorrow more will be made clear to you,” Harmouthes said, rising. “Sleep well, Ariston of Lindos.”

The young Rhodian finished his stew and fetched another helping from the pot. As he ate, the tale of Memnon turned over and again in his mind.

No words suffice to do justice to his deeds.

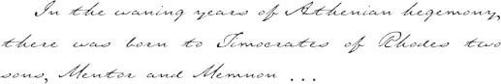

Many such phrases were readily identifiable to Ariston—they belonged to Thucydides or Xenophon—and the emotions invoked hearkened back to Sophocles. Still, something was compelling in the tale. Ariston pushed his bowl aside, moved his bag to the end of the table nearest the fire, and drew out his ink pots and reed pens, his last few sheets of papyrus and parchment. Quickly, he wetted a reed in the ink and put it to the papyrus:

Though exhausted, the Muses sang to Ariston, their voices strong and rich. He would not ignore them.

A

RISTON STIRRED FROM THE HARD BENCH THAT SERVED AS HIS BED, HIS

extremities tingling from a lack of circulation. Pale winter sunlight filled the kitchen, slanting through the bare limbs of oak trees on the slope behind the house. He reckoned it to be nearly midday. Ariston knuckled sleep from his eyes. Shivering, he stood and stretched, feeling a familiar ache in his back, arm, and hand—the aftereffects of a night spent in the Muses’ embrace.A light breakfast of bread and honey, dates, and wine waited at the far end of the table, along with a bundle of fresh parchment pages—

pergamene

of the finest quality—and new reeds to serve as pens. Of last night’s pages, Ariston saw no sign. The young Rhodian frowned. Of course, Harmouthes must have taken them. Who else? Doubtless the Egyptian did not understand the breach of protocol he had committed by disturbing a work in progress. More than once, Ariston had seen such infringements dissolve into violence. A volatile breed, writers, as proprietary toward their work as the sculptor or the painter.“He should thank his heathen gods I’m a temperate man,” Ariston muttered, pouring a measure of wine. He carried the bowl with him out into the peristyle, to take in the day. A chill breeze rustled the olive branches; the sky was a washed out shade of blue, crisscrossed with skeins of silvery clouds. Soft fluting emanated from the hallway leading to Melpomene’s room, interrupted now and again by the Lady’s hacking cough. Ariston followed the sounds. He paused to knock lightly on her door before easing it open.

Harmouthes sat on a stool near the window, engrossed in a complex tune of his native land. Melpomene sat upright in bed with pillows stacked high behind her, reading his previous night’s pages. “You have an extraordinary memory,” she said, after a moment. “I hope you don’t mind. When Harmouthes said you had spent much of the night writing, my curiosity got the better of me.” Melpomene coughed, her shoulders wracked with spasms. It took her several seconds to catch her breath. The old Egyptian glanced up from his flute, concern in his eyes. Ariston understood; even to him, the mistress of the house seemed paler, frailer. Her hands trembled as she tapped the pages back into a neat pile.

“No, madam, I don’t mind,” Ariston said. “If you’re feeling well enough, shall we continue?”

“I fear I shall never feel well enough, again,” she said. “Still, I would feel worse if I left my narrative unfinished. Are you familiar with the inner workings of Persia’s monarchy?”

Ariston brought his chair closer to her bedside. “To some degree, yes.”

“Through Herodotus, no doubt, or Xenophon. Perhaps Ktesias. Imperfect sources all. Among my people, it is customary for a new monarch to secure his throne upon accession. Civil war, you see, is as abhorrent to the Mede as it is to the Hellene. His uncles, cousins, even his brothers and sons were kept under guard or posted to the edges of the empire, well away from possible intrigues. In extreme circumstances, the new King would guarantee his personal security through execution and assassination. Such was the atmosphere in Persia the year before Memnon quit Rhodes.” Melpomene coughed, recovered, and sank down in her pillows.

“The Great King, Artaxerxes the Second, called Arsakes, died in the forty-sixth year of his reign. He had three sons. The eldest, called Darius, conspired against him and was executed; the second, Ariaspes, was a halfwit; that left only one, Ochus—as cruel and bloodthirsty a man as the gods ever created. Upon donning the mantle and peaked tiara, Ochus perceived threats from every quarter, some real, others imagined. He apprehended the need to strike first, and to strike without mercy. His minions decimated whole houses. They slaughtered males of fighting age, as well as grandfathers of four-score summers and newborns still damp from their mothers’ wombs. Even those not in his presence were in danger.

“One such was Artabazus, the husband of Memnon’s sister and satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia. Since he bore royal blood—his mother was a daughter of old Artaxerxes—Ochus ordered him to relinquish his satrapy and present himself and his sons in Susa. Knowing it to be a death sentence, Artabazus refused …”